Happy Halloween, everyone! Hope you’re all prepared for tonight. And may the gods have mercy on those of you who aren’t…

Let’s talk about scary movies for a moment.

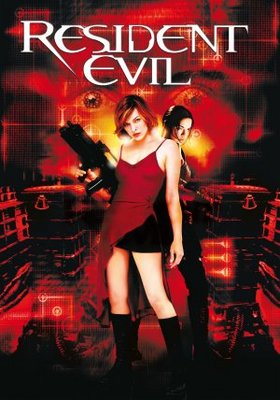

If you aren’t familiar, there was a long-running movie series called Resident Evil based off the long running game series of the same name, which also spawned a series of animated movies. But we’re talking about the live action ones. Well, the original live-action ones.

Specifically, I’d like to talk with you about the first one, written and directed by Paul W.S. Anderson. Rather than base the movie directly off the game story, Anderson decided to use lots of elements from the game with all-new characters. This gave him a lot more freedom in how he told the story, and let him structure the film for a general audience instead of specifically for fans of the game.

That structure is what I wanted to talk about. If you’ve been following the ranty writing blog for a while, you know I love pointing out how well this movie uses flashbacks. Seriously, it’s amazing. The movie’s pretty much a masterclass in how to do flashbacks well in a story. They all serve a clear purpose. They all advance either the plot or the story (often both). They all fit within the narrative and linear structure of the story. And none of them create fake-tension situations that are undermined by the present. You can read more about my rules-of-thumb for flashbacks right here, if you like.

So I figured, since it’s Halloween and all, I’d walk through these flashbacks one by one and show you how and why they’re so effective.

Now, you’re going to get a lot more out of this little rant if you’ve seen the movie. I highly recommend checking it out. It’s seasonal, it’s fun, it’s much more of an action-horror film than a gorefest. I don’t know if it’s streaming free anywhere, but I think you can rent it most places for three or four bucks? Also, kind of goes without saying but there are going to be some unavoidable spoilers in this discussion so… be warned.

Here’s a brief refresher for those of you who haven’t seen it in a while (or are just determined to go on without seeing it)…

Resident Evil begins with a few quick minutes showing the lab accident that kicks off everything before the lab goes into a drastic lockdown mode that seems to kill, well, everyone. And after that we’re with our heroine, Alice, who wakes up naked and wet on the floor of a bathroom, half-draped in a shower curtain and suffering from near-complete amnesia. Very quickly she learns she’s part of a security detail guarding a hidden entrance to the Hive, a massive underground lab/ testing facility operated by the multinational, multibillion dollar Umbrella Corporation. And the lab accident earlier has set a very nasty bioweapon loose down there, the T-virus, which has had, politely, some effects on the researchers and other staff members.

And we’ll stop there for now.

So let’s talk flashbacks. I’ll try to go over all of them and give you a little context for each one. I’m also going to mention where they are so if you’re actually doing your homework, you can skim around in the movie and find them.

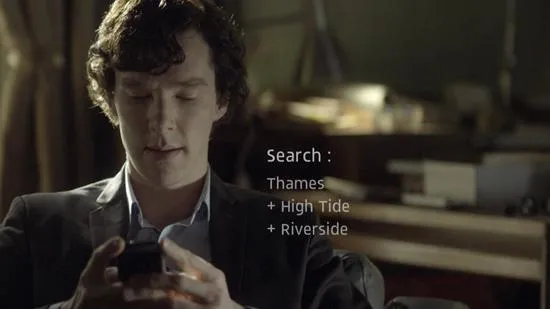

Our first one shows up a little over nine minutes in. Alice has woken up, staggered to the bathroom mirror, and is staring at her reflection when this flashback kicks in for a few seconds. She was in the shower, there was a vent, her eyes rolled up, and she collapsed, dragging the shower curtain down with her.

So this first one does a few things. It tells us right up front Alice didn’t pass out she was knocked out—this is something that was done to her, not something that just happened. It also establishes her flashbacks are very distinct from the “present’ story line in the movie—they’re in overexposed black and white, with echoey sound and a fast cut, glitchy quality that helps sell her fragmented memory. And it fits story-wise. This is something she’s focused on and trying to remember. It also fits because it’s relevant to what’s going on and it’s something we, the audience want to know. So on a few levels it makes sense we’re seeing this and not, y’know, last night’s dinner or something.

Also worth noting Alice’s reactions after this flashback because it’s very clear this is all the information she got from this sparked memory. She still doesn’t know who or where she is, or what’s going on. This is going to hold for all the flashbacks—she doesn’t get anything “extra” out of them. She sees what we see.

Our next flashback comes at eighteen minutes in. Alice has been taken with the security team to the underground train that leads to the Hive, and they’ve found an unconscious man on board. Alice stares at the man’s face and flashes back to her and him together and happy. Again, just quick flashes. Her in a gown, him in a tux, laughing, posing for photos together.

Worth noting that Alice had also seen a wedding photo of her and said man a few minutes earlier, and this flashback pretty much explains where that photo came from. It also connects the two for the audience—the man here now on the floor of the train (we’ll learn his name is Spence and he’s also suffering from gas-induced amnesia) is the man we saw earlier in photos. Whoever he is, Alice has a definite history with him.

Which brings us to the third flashback. Maybe 22 minutes in now. It’s mostly a recap of the first one as the security team commander explains what’s actually going on here and gets everyone up to speed. So as he’s explaining the computerized security systems and known side effects of the gas (short-term amnesia), we see Alice get gassed in the shower again—this time with an extra few shots to show us how the vents are hidden away in the walls.

So this one’s a little more structural—it’s a quick reminder for the audience. It emphasizes things are run by the computer (some of you know where that’s going). It’s giving us a bit more information about how thing are hidden and automated in Umbrella facilities.

Our fourth flashback happens three or four minutes later (just shy of 26 minutes in). We’re in the Hive now, and Spence offers Alice his leather jacket to keep warm. It’s the first time they’ve actually touched and it sets off a bunch of memories for Alice. Really specific ones showing she and Spence knew each other. Like, y’know… knew each other. Physically. As was the style at the time.

And that means now Alice knows something about Spence. He’s clearly someone she has a history with, and a history that involved, well, a degree of sharing and trust between them. As always, she doesn’t remember anything else, but it’s enough that she clearly decides he’s someone she can trust.

Notice the pattern here so far. All four of these flashbacks barely add up to fifteen seconds. They’re not slowing anything down. They’re all related to the actual events going on and the information the movie’s giving us (and Alice). And every one of them tells us something new—there’s very, very little noise. They all keep advancing out knowledge of the plot or the characters.

The next flashback doesn’t happen for almost half an hour—there’s a lot of action going on and dropping in a flashback would just disrupt the flow of things. Then around the 53 minute mark, Alice saves Matt from a zombie that’s attacking him and she recognizes this zombie. We get our longest flashback yet (almost ten seconds!)– Alice and this woman meeting in a deserted graveyard, where Alice is offering her access to the T-virus, Umbrella access codes, surveillance plans… for a price.

So… this one does a bunch of stuff. It’s suddenly casting Alice’s real goals and loyalties into question (at a point when she still can’t even remember them). It’s showing us she was part of a larger story than just the current events going on in the Hive, and making it clear Umbrella has been a questionable company for a while now. It’s also a nice reminder all these zombies were actual people—people we saw back at the start of this doing their jobs, chatting, drinking coffee, and just living their own lives.

And it doesn’t help that shortly after this Matt tells Alice the mystery woman was his sister. The two of them were gathering information to expose Umbrella’s illegal, unethical practices. His sister had found someone who could get them all the information they needed to get out with the evidence… but whoever it was they betrayed her. So now this flashback has Alice really questioning herself—and us questioning her, too. Amnesia-Alice seems great, but maybe if she had all her memories…?

Now, something happens around 70 minutes in that’s worth mentioning. Alice gets some memories back but it’s not set up as a flashback. It’s not in blown-out black and white. It’s not glitchy. And she’s not part of it. She just suddenly recognizes an area of the Hive they’re in and pictures it up and running and full of people. And she remembers what should be in a nearby lab– the cure for the T-virus.

I think this is worth noting because by breaking the flashback format here, the movie’s showing us that things are changing. Alice is getting more solid memories, and they’re appearing more solid because of that. The flashbacks are a clever device and being used well, but things are moving past the point of needing them and trying to force this particular bit of information into that format could actually be distracting at this point. And we never want our flashbacks to be distracting. Also, this scene is a little longer and somewhat talky but it’s happening at a time when our main story has slowed down a bit. Again, it isn’t messing with our flow.

So… moving on. One final flashback, and it happens just two minutes after the last one. They find the lab with the cure and it’s gone. The vault is empty. And as our heroes look around the lab trying to find some clue what might’ve happened to it… Spence has a flashback. And it’s a big one.

Turns out Spence was spying on that meeting in the graveyard, and he decided to steal the T-virus first. And almost 2/3 of his flashback is… the very beginning of the movie. All seen from his point of view. Spence caused the lab accident! Deliberately! To cover his theft.

(fun fact—if you freeze frame at the three minute mark in the very beginning, you can actually see it’s Spence right then! At 3:02, to be exact)

So, what does this last flashback do? It tells us what really happened to cause the lab accident. It reveals Spence as one of our main villains all along. And it firmly establishes that Alice, with or without her memories, is our hero—we find out her “price” for giving Matt’s sister all this evidence is that they use it to destroy the Umbrella Corporation.

Again, new information given in a way that adds to the tension, doesn’t slow down the pace of the actual story, doesn’t undermine anything.

See what I mean? Seven flashbacks in a movie that’s barely a hundred minutes. And heck, really all of them are in the first seventy minutes or so. And every one of them works for both the narrative and linear structure. Every one of them gives us information that’s relevant to “now.”

That’s some good zombie flashbacks.

Next time, I’d like to talk about how long all this takes.

Until then… well, enjoy Halloween.

And then go write.