Just when I thought I was done with making movies, they dragged me back in…

And by they, I mean me. I came up with this all on my own. I think it might be kind of fun.

In a perfect world where people listened to experts instead of YouTube videos forwarded by drunk Uncle Carl, we’d all be fully vaxxed, there’d be herd immunity, and we’d be gearing up for preview night at San Diego Comic-Con tomorrow. Fantastic, right? Alas, this is not that perfect world and SDCC is online again this year.

I’m not doing any panels this time around. Really the only big things I’ve got planned are maybe building one of my larger, long-overdue LEGO sets (you can vote here) and doing one of my big, more public Saturday geekeries (more on that next time). You know, where I live tweet a movie and talk about all the things it’s doing right (or wrong).

For the past few years, I’ve also tended to mark this viewing party with a movie-related blog post. Usually an updated version of my Top Ten B-Movie mistakes list. But this year I decided I wanted to do something a little more positive and maybe even a bit instructional.

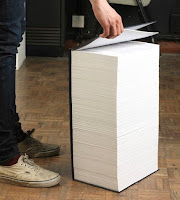

So this week we’re going to talk about about how to make a better B-movie. As in, if you and your friends were thinking of shooting a movie together, here’s a big pile of tips and hints. Today’s going to be about writing it, with advice based off my experience as a writer, screenwriter, and entertainment journalist. Then in our regularly scheduled Thursday post, I’ll offer some advice about filming said B-movie. That’s going to be based off my experience working on a few dozen B-movies and TV shows(some of which you’ve actually heard of), and also… yeah, my attempts to shoot a few low budget things with my friends. Which, y’know, you haven’t heard of.

Fun, right? Mildly interesting, maybe? I know a lot of you have no real interest in screenwriting, but I think some of the overall storytelling ideas here might still be kind of useful for you. They have been for me, anyway, in the long run.

So… let’s talk about writing a low-budget, fantastic B-movie.

First off, let’s be very clear on one thing. We’re talking about writing a very specific kind of script, and it’s kind of the reverse of what I talked about a few times in the past. This isn’t going to be a screenplay to enter contests with or submit to agents. It’s going to be a very solid script so you and your friends can make a good, cheap movie. It needs to follow some of the rules, but overall, this is just for you.

Second thing is all of this is written assuming this is a group effort right from the start. We’re writing it, but we already know our girlfriend’s directing, our friend’s going to star in it… or heck, maybe all of these people are the same person. Maybe I’m a writer-director-producer-actor. If that’s not spreading myself too thin… fantastic. Either way, this is the kind of stuff it’s good to know from the moment I start typing.

So…

1) Know What I’ve Got to Work With

If I’ve got a bunch of friends with Ren Faire costumes and armor, maybe I should consider something historical or fantasy. If I have open access to an office building, I should think about setting something in an office. The guy next door has an entire space station set in a warehouse he owns? Holy crap, you live next door to Roger Corman. Why are you listening to me—go talk to him!

Basically, I want to play to my strengths. If I’ve got a bunch of assets, I need to figure out the best way to use those assets. This can be a chance for some great creativity. We’ve got medieval costumes, one decent alien costume, and three or four really nice sci-fi props? Sounds like a spaceship crashed in the woods outside Camelot. Holy crap, was Excalibur really a power sword this whole time?

Also keep in mind—just because I’ve got something doesn’t mean I have to use it. I don’t want to cram a dozen random elements into my movie just because I can. The goal here is to tell a cohesive story, not to fit in every plot point I think of. Phoebe may have a fantastic pirate costume from that theme wedding, but maaaaaybe the story just doesn’t need a pirate. I know it’s hard to believe that, but it’s true. Simplicity can be my friend sometimes.

2) Don’t Write What We Can’t Shoot

One of the unspoken truths about screenwriting is it often comes with a list of requirements. Maybe they’re budget things, actor things, studio things, who knows. If we’re making a B-movie, we’re probably going to have a lot of requirements. My scripts are going to be a lot stronger if I start with these limitations in mind, rather than forcing the director to deal with them when they eventually pop up on set.

If we know we don’t have a lot of special effects to fall back on, let’s not write scenes that depend on special effects. If we know none of our friends want to show a lot of skin, I shouldn’t put in a lot of shower scenes and torn shirts. If I live in

Really, this is the flipside of my first point. Know what I’ve got to work with, but also be clear on what I’m not going to have. It’ll make the whole process easier in the long run.

3) Beware of Expensive Scenes

One of the first things people tell you about screenwriting is not to worry about budget. But, we have to worry about budget. We’re making a B-movie and doing a lot of it by calling in favors and debts. We don’t have money to burn on this thing. So if we can eliminate some essentially expensive scenes up front, that’s going to be a win for us.

Thing is, there are certain scenes that are very easy to write and look cheap at first glance, but the truth is they’re very expensive to get on film. I’m going to name a couple and explain why…

–Crowds—big groups of people on film are expensive for three reasons. One is that a responsible filmmaker’s going to give them food and drinks, especially if you’re not paying them (so at least buying lots of pizza and soda, plus enough plates, cups, ice, napkins, trash bags). Two is that you’ll probably need extra help getting them all to do what they need to do. Three is paperwork—if someone’s on film, they need to sign release forms for us using their image, even if we’re not paying them (especially if we’re not paying them). Essentially, crowds burn up a lot of our resources really fast.

–Food—let’s say I’m going to have someone take a bite out of a hot dog in this scene. That’s all. They grab a hot dog at a backyard barbecue, have one bite while they’re talking, put it down. So that’s one hot dog for the master shot, and one for the reverse master (because they’ll need an unbitten dog to take a bite out of). One for each angle of the overs. One for the coverage. So at the bare minimum, we just went through five hot dogs. And that’s assuming we got everything in one take. This one-bite shot can add up to three or four packs of hot dogs and buns really fast. And again—this is just one person having one bite. And we’re not even considering someone’s going to have to keep cooking them, so we’re going to need a working grill, fuel for the grill… seriously, just cut the food scenes.

–Kids and Animals—if we have kids and animals as possible assets to use for our movie, that’s fantastic. But it’s a safe assumption that every scene with kids and animals are going to take twice as long to shoot. That’s the big reason they’re expensive, especially on this level. They use up time we could be using for other things.

–Getting dirty—throughout the course of a story, somebody could get smeared with dirt or blood, maybe get a sleeve torn, get their hair mussed up, something like that. Maybe they just fall in the pool. Heck, maybe they’re just putting mustard on that hot dog. If I see a change like this happen on screen—let’s say Phoebe gets mud thrown on her shirt—then we need multiple shirts for every single take of this (again, I refer to the hot dog). Plus, it’s another time expense as the actress playing Phoebe has to go get changed, maybe clean mud off herself, fix her hair back to how it was. Again, looks simple on the page, but it adds up really quick when you talk about production. I’ve been on shows where they’ve bought four or five matching shirts for gags like this, and it still didn’t end up being enough.

–Night shots—it’s hard to tell sometimes, but exterior night shots in movies and television often use a lot of lights. Dozens. Yes, even some found footage stuff. There’s a real art to making well-lit darkness. That means good night shots require someone who knows what they’re doing and the equipment they need to at least do it passably well. If I have to have a night shot… could it maybe happen in a well-lit parking lot?

Okay, this one got really long, but you get the general idea. I could probably come up with five or six more examples. Thing is at this level, I need to think about how stuff will actually be shot and what that could involve.

Moving on…

4) Know What I’m Writing

Once we’ve juggled all these assets and limitations with our own goals and desires, we should have a pretty clear idea of what kind of movie we want to make. Yeah, it’s a B-movie, but is it a supernatural thriller? Urban fantasy?

Also, who is this for? Who’s our audience? Are we looking to make something family- friendly or a little more for the 18-35 range? All these decisions should help shape some scenes a bit.

5) Know Who My Hero Is

I’m mentioning this because it’s always the #1 problem when I’m watching my Saturday geekery B-movies. Like I was just saying about the genre, when we’re hammering out this story together, we need to figure out who our main character is. Is it him? Is it her? Are those three our mini-ensemble? This is storytelling 101—who should my audience be paying attention to? Who should they be rooting for?

Once we know who they are, we need to make sure they’re a good character. And, weird as it may sound, Wakko being our main character means they should be, y’know, the main character in the movie. There should be more pages about them than about Yakko. Or Phoebe who’s willing to wear that tiny bikini on film. The hero is the person we should be spending the most time with. They should be the one driving the plot forward.

6) Be Cautious of Camp

This is a tough one. At this budget level, it’s really tempting to just wink at the camera and make a joke out of how silly that costume is or that we’ve go three people standing under a paper-and-sharpie banner that says “

Thing is, this type of comedy wears thin really fast. One of the secrets of camp is that the best examples of it never give the audience that little nudge-nudge, wink-wink. They play themselves completely straight. Too much obvious camp makes it look like we’re not taking this seriously, at which point… why should the audience take us seriously as filmmakers?

If we’re not making a comedy, resist the urge to lean into comedy. Especially as an excuse. We want to embrace our strengths, not mock our weaknesses.

Speaking of which…

7) Think Big

I know with everything I’ve said so far, it probably feels like our best bet is that old indie standard “three people trapped in a hotel room that looks a lot like the bedroom of my apartment.” But just because we don’t have any money doesn’t mean we can’t have big ideas. We can’t have battlemechs fighting kaiju, but that doesn’t mean we can’t have a big concept.

There are so many examples out there of high-concept, low budget movies. Saw is literally just the old bar question of “what would you do to escape this?” asked with some low level special effects. Primeris a time-travel movie where their big expense was some cardboard boxes wrapped in tinfoil. The Blair Witch Project. Monsters. Chronicle. All of these movies are really big story ideas that people figured out how to do in small, low-budget ways. We should absolutely aim as high as we can.

Okay, just a few more…

8) Format It

I’ve talked about screenplay format in the past. Technically, yes, if I’m only writing this to shoot with my friends, it doesn’t matter if I’ve got the format down or not

But… if I do have it formatted correctly, there’s a bunch of really helpful tricks I can use. Like timing my script. You may have heard that one page is about a minute of film time (according to a good friend of mine who’s a script supervisor it’s closer to 53 seconds on average, but one minute’s an easy rule of thumb). So if I’ve got this in the right format, I can immediately look and know this scene is probably going to run long, or that the whole thing is barely an hour.

Another good one. We should generally figure it’s going to take about 90 minutes to shoot one page (again—talking about a properly formatted script). Some may go faster, some slower, but in my experience 90 minutes a page is a good estimate. Which means now I can schedule a shooting day (more on that next time)

It may be a bit of a pain, but there are some serious advantages to formatting this correctly. I don’t even need special software—if someone happens to have it, cool, but I’ve written pretty much all my scripts in Word with a few formatting macros set up. Hell, my first few I just wrote ‘em and then went back through and got all the formatting right.

Yeah, fine, maybe you can come up with an all-new, far-better way to write and format screenplays. You’re not part of the

9) Top Screenwriting Tip—RIGHT NOW

I’ve mentioned this before so I’ll give you a link and not go into it too much here. Because this whole post is getting really long. Super short version, if it’s not on screen right now, it shouldn’t be on the page. Are we shooting backstory in this scene? No? Then there shouldn’t be any backstory on the page. No inner monologues or struggles. No character sketches. No notes to my friend (or future me) who’s directing this. What’s on the page should be what’s on the screen right now, and vice-versa.

I know it’s tempting to put all that stuff in the script (it’s got to be somewhere, right?). But one of the reasons people growl about details like this is because it messes up all those estimates we were just talking about. Because none of this stuff actually gets filmed.

And now, my final big tip for writing a B-movie…

10) Actually Write The Script

Because this is just us and our friends making a movie, it kinda feels like we don’t need to bother with putting the whole thing down on paper. I mean, we hashed out all this stuff I’ve been talking about last night over pizza and rum, right? We know what genre this is, who our hero is. The big stuff’s done, we can work out all the fine details on set.

The truth is, a complete script just makes it much easier to tell a cohesive story. The less I plan out, the more things veer off the path. If the actors want to ad lib on set and the director wants to let them ad-lib and the ad-libs are actually useful and germane to the discussion, as someone once said… cool. But until then, I need an actual, finished script. For all those formatting reasons I mentioned above, but also so I can actually plan this out.

Plus, it’s just more professional. True story—I worked on a low-budget TV show and one episode… we didn’t get a script. Seriously. This was an actual, on-television show and they didn’t give us a script. The actors didn’t have anything to rehearse. The costumer and I got called into the line producer’s office to discuss prep and he just said “Get some military stuff.” When we tried to ask what year, what branch, dress or combat, for how many people… he actually got annoyed with us and said we’d have to “think on our feet” for the next episode.

Don’t be like this to your cast and crew. You can be more professional than that. Hell, you can actually be more professional than that professional.

And look at that. There’s ten tips for writing a better B-movie script. And a ton of links to guide you back to some other stuff I’ve said about the process.

Next time, we’re going to give this script to the director (who, granted, might also be us) and talk about a couple ways to make sure this whole filmmaking thing goes smoothly and maybe gives us something we’re willing to show people.

Well, go write.