Easy geek reference up there for you.

So, this week’s little rant is sliding in under the wire. To be honest, I’ve been buried under a ton of last-minute stuff for work. Plus the holidays. Plus some family stuff. I can’t be expected to keep up on all of it.

Well, that’s not true. It’s a bit of a cop-out, really. If I’d managed my time a bit better a lot of this would’ve been done on time. There were even two or three times this week I remember thinking “I need to start working on this week’s ranty blog post.”

Cop-outs suck, don’t they? You’ve made an investment in some piece of writing and then wham! Out of nowhere the writer just does something lame. They’ll change the rules or deliberately ignore continuity and just try to bluff their way through. Epic stories that don’t deliver. Mysteries that aren’t explained. Ominous foreshadowing that never pays off. All of these are cop-outs.

The very first story I can ever remember telling had a cop-out ending. I was about eight years old, it was summer, and Mom had taken us to the beach even though I wasn’t feeling well. Somehow I ended up sitting with the father of my friend Todd, while everyone else played in the water, and I spent the time regaling him with the epic tale of G.I. Joe fighting off the Intruders.

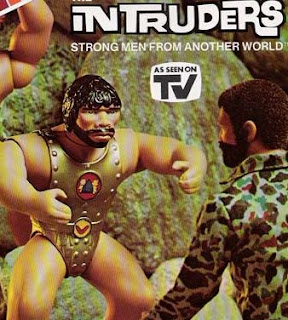

For those of you born after 1980, G.I. Joe used to be just shy of a foot tall and had fuzzy hair. You could even shave him. He was also firmly grounded in the real-world military. When Star Wars shifted the toy paradigm to science fiction, GI Joe suddenly gained a bunch of new friends, like the superhero Bulletman and the cyborg Mike Power. And enemies called the Intruders which were a race of alien bodybuilder midgets who  wore metal leotards… sort of…

wore metal leotards… sort of…

Anyway, on with the story.

You see, the Intruders came down in asteroids. And they all crash-landed at GI Joe’s secret base. There were lots and lots and lots of them. In fact, there were a million of them. So GI Joe was shooting at them with his gun and he shot ten of them, and Mike Power was kicking with his bionic leg–

(Mike Power had one bionic leg. Just one. Even at the age of eight, I could see the gigantic flaws in this bit of cybernetic engineering.)

–and Bulletman used his ray to lift a bunch of them into the air and send them away. This pattern of violence was repeated enthusiastically twice or thrice before I declared all the Intruders defeated.

Not so, Todd’s father told me. A million is a lot.

I conceded this, and explained that the above mentioned pattern of gun-kick-ray happened again. So now they were all gone.

No, he said with a smile and a shake of his head, a million means there’s a lot more left.

I nodded, then said that Bulletman had used his ray to scoop up everyone who was left and send them away.

It seemed like a very solid ending at the time.

Granted, it’s easy to excuse an ending like that from an eight year old, but far too many adults use them, too. Except for poor spelling, there isn’t a much more glaring sign of poor writing than a plot thread that winds up with a cop-out. It shows the writer didn’t think things out, or just couldn’t be bothered to.

A few common types of cop-outs.

Changing the rules–While it completely fits the story it’s told in, the title reference of this little rant is a perfect example of changing the rules. In the midst of this serious contest of life and death, we find out it wasn’t a fair contest. We’ve been told within the story that X + Y = Z, but the writer suddenly announces X + Y can also equal Q. This usually comes about because the story has been written into a corner and the writer won’t take the time to go back and change things (when the ancient Greeks did this, they called their cop-out deus ex machina). As Billy Wilder once observed, a problem in your third act is really a problem in your first act.

Changing the rules is inconsistent and it breaks the flow. William Goldman used it for comedic effect in The Princess Bride, but it’s doomed to almost certain failure in anything except a comedy. Heck, thanks to Goldman it’s going to look pretty tired in a comedy, too…

The so-called twist–This is a more specific type of changing the rules. I’ve set out the rules for a good twist before, and they’re pretty simple for anyone to figure out. That’s why it’s so frustrating when a writer has Debbie pull off her wig and announce “Hah!! I’m really Larry’s second-cousin!!!” This is often followed by flipping through pages to figure out who Larry is and why his second cousin would have it in for everybody.

Usually a poor twist tries to solve one problem in the story at the expense of the story itself. A weak twist isn’t just a cop-out for a plot thread, it’s almost a guarantee the manuscript will end up in the large pile on the left.

No payoff –Few things are as annoying then to go through a story waiting to see the two enemies clash or to learn the answer to the mysterious puzzle that’s plagued out heroes… only to not get it. The enemy gets away. The mystery gets skirted over. It just leaves the reader feeling cheated.

Sometimes it’s not even a question that’s not answered, it’s just a payoff that never happens. When the climactic, world-altering final battle occurs off-camera and we just see the characters talking afterward about how amazing it was, that’s a cop-out.

Just plain weak–– Sometimes when a writer uses a cop-out, they’re just choosing the path of least resistance. It’s quick and easy and wraps stuff up. Oh, he was dreaming and she was insane. Sometimes an ending can seem solid, but it’s still weak because of the promise of something bigger. A worldwide alien invasion is awesome. A worldwide invasion where the aliens can be defeated by tap water… not so much. Remember, a story can be weak by inclusion just as much as by omission.

And there you have it. I’d put more, but, as I mentioned before, I have a lot of work to do still.

Plus, I’m really Larry’s third cousin.

Still open to suggestions as we head into the holidays. If not, next time I’ll end up blathering about women I’ve dated or something.

Until then, go write. At least your Christmas cards.