Very, very sorry it’s taken me so long to get something up. I’m in the home stretch for the new book and it’s eating up all my time. I haven’t had a chance to write out the animation post. Or stay caught up on email. Or… well, many other things.

Anyway, here’s something a little different. And it’s huge to make up for the time off. And there’s lots of pictures to help you deal with the fact that it’s so huge.

Here’s one of those interviews I did a while back. I’d wanted this to be a conversation I had with Nora Ephron back in 2009, but I can’t find my original transcript and don’t have the time to find the recording and type up a new one. Alas, this has now ended up becoming an Ernest Borgnine memorial piece…

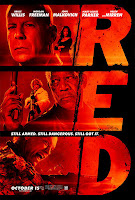

So, here’s a very fun conversation I had with Jon and Erich Hoeber, two screenwriting brothers who wrote the action-comedy movie RED, based off the comic miniseries by Warren Ellis. They’ve since moved on to do a few other big-named movies and are working on a sequel to RED. Jon and Erich were probably one of my favorite interviews I ever did in my years at CS, and we talked for almost an hour about the many aspects of screenwriting. It was far too much to use for the space I was allotted (despite repeated begging to the editor), and it’s even too much for here. So what you’re seeing is a somewhat truncated version of that interview (about 2/3 of it).

A few points, but you’ll probably figure it out as it goes. I’m in bold, asking the questions. Keep in mind a lot of these aren’t the exact, word-for-word questions I asked (which tended to be a bit more organic and conversational), so if the answer seems a bit off, don’t stress out over it. If you see a long line of dashes (————) it means there was something there I didn’t transcribe, probably because it was just casual discussion or something I knew I wasn’t going to use in the final article. Any links are entirely mine and aren’t meant to imply Jon or Erich endorsed any of the ideas here on the ranty blog. It’s just me linking from something they’ve said to something similar I’ve said. And by the very nature of this discussion, there will probably be a few small spoilers in here. If you haven’t seen the film yet, check it out. It’s fun and you’ll get a bit more out of this discussion.

Material from this interview was originally used for an article that appeared in the September/October 2010 issue of Creative Screenwriting Magazine.

So, anyway, here’s me speaking with Jon and Erich about writing RED.

==========================================

So, let me ask this. Why did you guys end up writing together? What made you pick your brother as a writing partner?

E: We kind of fell into it. My background is music. I studied composition and conducting. At the same time my brother was in film school. He called me to write some music for a film he was making. It was, in a way, the first time we’d reconnected as adults, because as kids we’d fought like crazy. So I wrote the score for his movie.

A couple years later, maybe a year later, we were both in Los Angeles. I’d come out here to sell out and write jingles or something.

Probably if we had any idea how hard it was going to be we would’ve been stockbrokers. Whatever it is people do who have real jobs.

So, how did you guys end up on RED? Was this something you went after or something that got brought to you?

J: It’s interesting. First of all, we’ve been big fans of Warren Ellis for quite a while. What’s awesome is that we share a manager with Warren. So we were able to run around RED and try to set it up with a little inside help, which was great. But it was also a small, obscure-enough book that we were sort of operating outside the system. We weren’t having to do battle for a big-money title.

E: We also knew at that point Gregory Novak. Around that time he had just started working for DC and he’s an executive producer on movie. We got him involved We got Mark Vahradian, who’s another producer. And we ran around and tried to set it up.

When was this?

E: Initially we got hold of the book… I would say about five years ago. We tried to set it up then and we failed. But we always liked it and we always wanted to get it done. And then a couple years later we had the opportunity to try again.

J: Mark at that point had joined forces with Lorenzo diBonoventura, who’s a powerhouse.

E: So we tried again and we were able to set it up with Summit Entertainment. We had written a very detailed treatment, and they basically bought it just off the treatment.

J: There was a fantastic meeting after they had agreed to hire us to write it, where they called us in for a ‘creative session.’

E: It was the best notes meeting we ever had.

J: We sat down with them and all the producers were there and their assistants were there. They said ‘Well, guys, we really like the outline you wrote and we think this’ll be very cool. So don’t screw it up.”

E: That was it.

J: It was like that moment in Forrest Gump– ‘I shure hope ah don’t let him down.” (laughs). Summit has been fantastic. They have things to say and great opinions, but in a very collaborative, open way, as opposed to ‘Here are the studio notes!’ My way or the highway.

When you made the deal with Warren, did you buy the rights outright or was this a handshake deal or what?

E: We hadn’t bought the rights ourselves but we had agreed with our manager and with Warren Ellis that we would try to sell them and then they’d have to make a deal with both him and us.

J: No money exchanged hands but it was a secured position.

This movie has a really slow start. It’s almost kind of an indie film, where we go for ten or fifteen minutes and… well, nothing happens. Was that a tough sell?

J: The opening, from a writing point of view, was a fascinating thing for us to play with. Obviously when there’s a marketing campaign you know exactly what you’re getting into. But generating a cold script, when this was first crossing people’s desks, it was a very odd departure to have seven pages of relationship going on between two people. Somebody at work and somebody at this house. And seeing there were tiny little bits of oddness about him. You know he’s not normal, but what’s his problem? Why does he have this empty life? He’s sort of pretending to be a human being but he’s not quite a person. And the fact that it goes on– when was the last time you saw an action film that didn’t start with action? The fact that you’re talking about this as ‘indie tones’–

E: It actually makes us smile.

J: It was something that was a big ballsy choice for us. For us the most important thing is that it’s a character piece that turns into an action movie. Or is also an action movie. As opposed to, here is our high-concept action structure that you’re desperately trying to stuff character in, which is how the jobs usually go.

Now, there area lot of differences between the graphic novel and the film. Were these things that the studio wanted from the start, or were these things where you looked at it and said “cinematically, this would work better if…” ?

E: That’s very perceptive. Our first take was hewed a bit closer to Warren’s original tone. We loved the character he’d created, this guy leading this empty life and trying to figure out how to be human. But obviously his original work was very, very, very dark.

J: And we talked about that. Wouldn’t it be cool to do a stripped-down, lower budget, John Boorman-style action film. And that’s neat, but it’s sort of unsellable.

E: We came up with this very low-budget, very bloody version, and no one wanted to buy it. Then when we revisited it a couple years later we sort of thought what if you just used this character as a departure, a starting-off point. This relationship as a starting-off point. What if this guy becomes sort of a metaphor in a way for what happens to people when they retire in general.

J: And Warren Ellis’s theme of weapons of the Cold War left over, sitting around.

E: Yeah, this dangerous, unexploded ordnance that’s left sitting around in the form of these people. And what if you sort of expand that world. So that led us to invent and create many, many more characters to populate this world.

J: And ended up as a radical departure from the source material. But the big question we asked ourselves at that moment was the tone question. What kind of a movie is this going to be like? At the end of the process it always ends up being very clear. Along the way it’s perhaps the most challenging balance of the whole creation process on this one. A touchstone for us was going back to Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid. Butch and Sundance was something we felt like you hadn’t seen in a long time. It had that brilliant balance of character and humor but also those real stakes. People get killed. Our heroes die at the end of the movie. You buy this threat that’s chasing them all the way along.

E: There’s not a lot of movies that occupy that space, and I don’t know why. But the idea that you could have real fun and real jeopardy at the same time is something that’s very interesting to us.

J: Then, thematically, once you started playing with the idea of older actors, older characters with these massive histories behind them, that became another big driving force in the movie. That was awesome.

E: We actually wrote this part for Helen Mirren. We wrote it with her in mind. You never do that because you always get your heart broken. For Helen it worked because you’re writing a part for her that she hasn’t played in a very long time. She’s been in gangster movies before, but everyone knows her now as the Queen. But if you put a machine gun in her hand… One way to sell this movie is just say ‘Helen Mirren with a machine gun’ and everyone starts cracking up.

J: It’s an amazing thing to take these iconic bad-asses and bring them back to that, which is a big twist of genre and a lot of popular perceptions.

The whole idea of the title, the meaning behind being flagged “red” is radically different. When did that happen?

E: In Warren’s book it’s a code where he becomes active again. We initially tried to put that in the movie but it didn’t really work. And there was some discussion about whether the title was going to change or not. But Summit really liked the idea of using the original comic book and we did to. So we thought, well, if we’re going to use the title RED we better get it back in here somehow. We came up with ‘Retired- Extremely Dangerous,’ which has now become the tagline for the movie. And that seems to work pretty well. Everybody thinks that’s funny. And obviously having Ernie Borgnine deliver it is just great. He is the nicest guy.

J: Celebrated his 93rd birthday on set up in Toronto. Bruce took him out, we took him out. Just partying like a rock star on his 93rd birthday.

What’s your usual process? Are you outline guys, notecard guys, do you like to get it all in your head and dive in on page one?

E: We write treatments. Usually we’ll brainstorm the movie and one guy will go off and write a treatment, and then he’ll flip it over to the other guy.

J: Jointly we create these incredibly elaborate, detailed treatments. Which tend to be sort of the contract to keep everybody on track. After the treatment’s set we just start breaking it up. You write the first ten, I’ll write the next ten, and we start passing pages back and forth. So everybody knows exactly what the other guy’s doing. But our first push is to just get to the end of the movie as fast as possible. Don’t look back too much, try to keep it alive and bright. And sometimes one of us’ll latch onto a certain character a little more than another. But once we get to the end we just start going through it again and again and again. That’s the genius of partnership. Constant fresh eyes. Constant challenge. Constantly challenging the other person. What if we did it this way? What if we did it this way? So we are fast but massive rewriters. Never stop pushing on it. Which is why a lot of our scripts tend to be tightly integrated, complex movies where you’re juggling a whole bunch of things at once.

E: No matter how well you outline there are things you can only discover when you’re writing the script. Voices and the way people do things and the little things that integrate from scene to scene along the way. Jon actually invented the Ivan-Victoria love story when we were writing the script. It wasn’t in the treatment. Things like that are things you kind of discover along the way.

J: I’m always amazed when I hear writers–most of them tend not to be pros– but when people say ‘I don’t outline. I like to discover it.’ And I’m like, man, I hope you discover an ending along the way, otherwise you’re going to be in a world of hurt.

E: We’re big believers in our structure. If we have a structure that we really like than we never really worry that we can fill it in. The big question is what’s the best way to do it. But we always start knowing exactly how the thing is structured.

J: As opposed to tone. Tone changes. Tone flexes. Sometimes you just realize the thing you’re working on is a little funnier or a little a darker or a little different than you really thought once you start filling it out. That’s a very odd and interesting part of the creative process.

How much of an outline are we talking about?

E: We sort of do a ten to fifteen page treatment that pretty much says what every scene in the movie is. But it’s short enough that it’s not unmanageable. That you can’t just work with it quickly and move things around when you’re developing it. If you start to get bigger than fifteen pages, for us, it starts to become a big enough document that you start to get lost in it. So we try to keep it short enough that it’s manageable and long enough that it has all the information in it.

J: It’ every scene listed and sort of an emotional check-in of where the characters stand. What the beats and changes and emotional arc are.

How long does it take to get a draft?

E: Usually about three weeks, I guess.

J: There’s two levels to that. There’s the first pass through the treatment which generates 120 pages or 110 pages, and that’s probably three weeks. But I think it’s probably another three weeks of going back and forth before I feel like it sort of looks like a movie. He says three, I’d say six to get it to what I think you’re asking.

E: We rewrite constantly, and the more we do it the more complexity and refinement we get. By the time we gave Summit our ‘first draft’ we’d been through it many, many times.

J: But it was great because it was then at the point that they read that first draft and greenlit the movie. And I have to throw out credit there to the producers, who in this case were incredibly about challenging us on things without telling us how to do anything.

E: We’re at our best when someone tells us ‘Can you make this better?’ and we’re at our worst when they say ‘Do it like this.’ Because if they say do it like this you can only do it like that, and we always feel trapped.

J: Because maybe the solution to that line or that character or that problem has nothing to do with that scene. It’s an act and a half away in the movie.

One thing that really amazed me is that tonally this movie is so spot-on. How did you manage that? Comedy is usually tough to pull off in a comedy film.

E: One thing is, we do a lot of comedy but most of our comedy is not comedy that’s making an obvious joke. It’s comedy that comes out of character. All the characters take themselves seriously, but they have very different worldviews. So John Malkovitch has a way of seeing the world that is the complete opposite to the way that Sarah sees the world, and the two are naturally going to be funny when they’re put up against each other. If you do it where it is really character based as opposed to more slapstick, then you get away with more comedy closely connected to drama.

J: Because the drama comes from the same place the comedy does. It’s all character driven, as opposed to trying to just make up a situation. The other thing, though, is that Eric and I have always written in a lot of genres. We love to go see all kinds of movies, we love to go write all kinds of movies. And we’ve been doing that for a long time, much to the annoyance of our management.———– It’s nice to have all those tools in the wheelhouse, which in a movie like RED really come into play. You have to have this mystery-thriller line to hang it all on, which ultimately no one will care about but if you can’t make it look good people will flag you for it.

E: And you’ve got a little bit of love story. A little bit of action. A little bit of comedy. The trick is how to make it all one thing. That is to say, it all has to come from the same place. It all has to come from character. It’s not like you’re taking these things and sticking them together. You’re taking the character, which is the heart of this movie and the heart of any good movie, and finding different ways to express that character.

It’s apparent early on that the mystery behind Moses getting targeted is a lot more elaborate in the film. Did that grow out of having a larger cast or vice versa?

E: I think in a movie like this you never care that much about what the mystery is. You just want it to work.

J: After the fact, especially.

E: Yeah. It’s sort of a MacGuffin that allows you to let the characters do what the characters do. We were sort of tweaking what that mystery was all the way through the script. At the end of the day, it was simply what will sound interesting enough and what will mechanically work well enough that we can take several steps to get there. I guess… we don’t care about it It’s not where out bread is buttered.

J: We don’t care about it? (laughs)

E: Well, we care about it. You have to do it well enough, but it’s not what makes the movie great.

J: Right. It gives you a framework to have the characters that make the movie great. You can’t ignore it, but that’s not why anyone’s going to see this movie.

E: At the end of the day you’ll remember if it worked or didn’t work.

J: But what you’ll remember is “Old man, my ass,” or “I trained Kordeski,” or “If she didn’t love me, it would’ve been in the head.”

Let’s talk about some of the new characters, where they came from, what story-need they grew out of. Sarah’s probably the closest to “in the book,” the person he calls on the phone every other day or so. Why did that part expand so much?

And into a love interest?

J: It’s always good to have a girl in the movie. (laughs)

E: Part of it is this. Warren starts with the premise of this sort of extremely dark character. He’s done this his whole life and as a result he’s sort of become inhuman. He’s not quite a human being and doesn’t know how to be a human being. Starting with that premise, we asked ourselves the question, how do you develop that character. And how you develop that character is across the course of the movie he realizes there is more for him than just being this old piece of the Cold War. That he can have a life, that he can have a love interest, that he can sort of become human. If you imagine that now as his arc, then Sarah is the character who can, across the movie, start to transform him.

J: It’s also great to have a character who’s an outsider to this group of insiders, just from a sort of exposition and comedy point of view.

E: You’ve got a straight man with all these killers.

When did the idea for Cooper, or someone in that part, come into this? He’s a younger version of Moses, but there are some very distinct differences between them.

E: Cooper is… obviously we needed a great antagonist. Everybody in this movie has a little arc, and obviously Cooper does, too. What’s really interesting is there are big cultural differences in the CIA, between what it was like 30 or 40 years ago when people went to all these Ivy League schools with this sort of blue-blood culture, almost. Also this sense of we do what we have to do and we don’t really talk about it. Now the CIA is different. It’s a little bit more corporate and a little bit more professional, in a certain sort of way. In a certain sort of not-necessarily good way. So these were some of the things we were thinking about when we were developing Cooper.

J: For me it’s a real cornerstone of how Eric and I write, which is about genre twist. Any movie of size is going to be a genre movie in some fashion. You’re going to have seen virtually every character before. So for us the question isn’t going to be how do you come up with those characters, it’s what are we going to do to show you something you’ve never seen before within a genre that you’ve seen a thousand times before.

E: How do you take that scene you’ve done a hundred times and do it fresh.

J: For us a big example was Cooper’s introduction. He’s on the phone, he’s talking to his wife, he’s talking to his wife, talking about kids, he’s got to get milk–and he’s killing somebody. And any time in a scene you can do two things at once it’s obviously a good idea. You’re establishing Cooper and you’re also really setting a lot of tone for violence and comedy that runs throughout the movie. For us it’s really about those little mini-moments that end up having these big impacts and big ripples. Like you said, he’s a junior version of Frank.

E: Almost every scene that we wrote is in the movie, but there’s one scene that’s on the floor, where Cooper is explaining to his wife how he fell down the stairs and got his shoulder dislocated. We know that Frank did it. You kind of see on her face that she knows that’s not true, but it’s a very subtle thing and I think it slowed the movie down too much, so that scene isn’t in. This movie, very surprisingly, there’s very little of it that’s not on the screen. In part, I think, because it’s so tightly plotted that almost all of it’s necessary.

==========================================

And that’s that. I’m hoping to be back on track later this week, but just in case I’ll warn you it may be another interview.

One way or another, go write.

It’s what I’ll be doing.