Very sorry this is very late. I ended up with a clever thought about how I could restructure the whole thing. And then ha ha ha ha I kind of slashed half my fingertip open while working on some little toy soldiers (always be extra-careful when you’re using fresh X-acto blades, folks) and the bandages made typing a little challenging for, oh four days.

But here we are. Finally. For one last blathering-on about structure. This is the cool one, though.

So, I started off talking with you about linear structure, and then I talked a bit more about narrative structure. This week I want to combine these two and talk about dramatic structure.

As the name implies, dramatic structure involves drama. Not “how shall I recover from this sleight, woe is me” drama, but the tension and interactions and momentum within my story. Any story worth telling (well, the vast, overwhelming majority of them) is going to involve a series of challenges and an escalation of tension. Stakes will be raised, then raised again. More on this in a bit.

Speaking of which, before I dive in… okay, look, on one level I hate breaking all this stuff down and quantifying it because we’re talking about art. We’ve all got our own likes and dislikes and styles and methods, and there’s rarely any good, one-size-fits-all advice The art part of this is personal, and we should all be a bit cautious when some guru starts telling you how stories go together and slaps down graphs and charts or some nonsense like that.

So. with that out of the way… let me dive in and tell you how stories go together. I’ve got graphs and charts to help out.

Now, dramatic structure means I want to arrange my story so tension is rising. The plot needs to advance. Characters need to make decisions, and those decisions should have an effect on them and what’s going on around them, for better or for worse. Usually for worse. It may sound silly to say out loud, but tension should be higher at the middle of my story than the beginning, and higher at the end than it was in the middle. That’s just common sense right? Nobody wants to read (or write) a story that gets less interesting and compelling as it goes on. Or a story that starts sort of compelling and then stays… sort of compelling, and at the big climax is sort of compelling. I mean, maybe I’m just weird that way?

Mind you, these don’t need to be world-threatening challenges or gigantic action set pieces. If the whole goal of my story is for science-nerd Wakko to ask out popular girl Phoebe, a challenge could be working up the nerve or just finding the right clothes. But there needs to be something for my character to do to bump that tension line higher and higher. Stand up to the bully. Get to work in time for that important meeting. Come up with $30,000 by five o’clock on Friday to save Aunt Dot’s car wash. And, yes, defeating the cyborg ninja werewolf from the future so I can deactivate the terraforming device before it turns North America back into primordial tundra.

So let’s talk and let me show you some fun visual aids. On all of these graphs, the individual points are going to represent the linear structure. I’m going to be using the alphabet to mark them because we can all recognize that order pretty quick– A, B, C, D, and so on. Our X-axis (oooh, look at me, talking all mathy and sciencey) is going to be the progression of the story—our narrative structure. Think of it as the arrangement of plot points from the first page of my story to the last page (and damn, I wish I’d thought of that explanation earlier). Finally, the Y-axis is going to be our tension levels—dramatic structure.

Got all that?

Also, apologies up front. I didn’t realize how rough these graphs would be shrunken down. Sorry. Just open ’em in another tab. Also graphic design is my passion, yadda yadda, moving on.

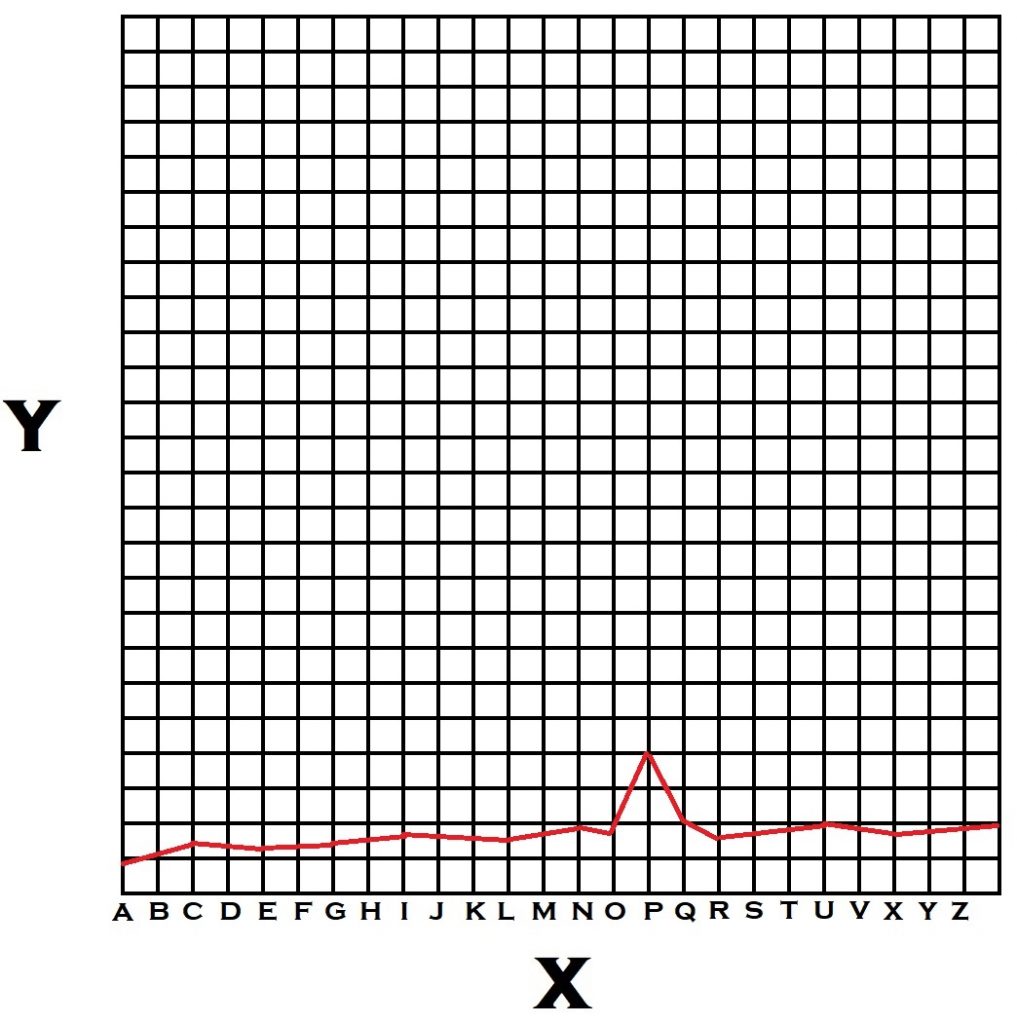

Okay, let’s do an easy starter graph.

This is the story of me sleeping. It’s pretty simple. We start when I go to bed, and end when I waking up. It’s told in a linear fashion, so the linear and narrative structures line up. There’s a brief moment in there when a cat woke me up (maybe Julius or Alucard?) and I went back to sleep, but that’s pretty much it as far as dramatic tension goes.

Like I said, simple. Really, this is a story where nothing happens. It’s pretty boring. You may notice it’s pretty close to a straight line. A flat line, really. And if you’ve watched a lot of medical shows, you probably know what it means when they say something’s flatlined…

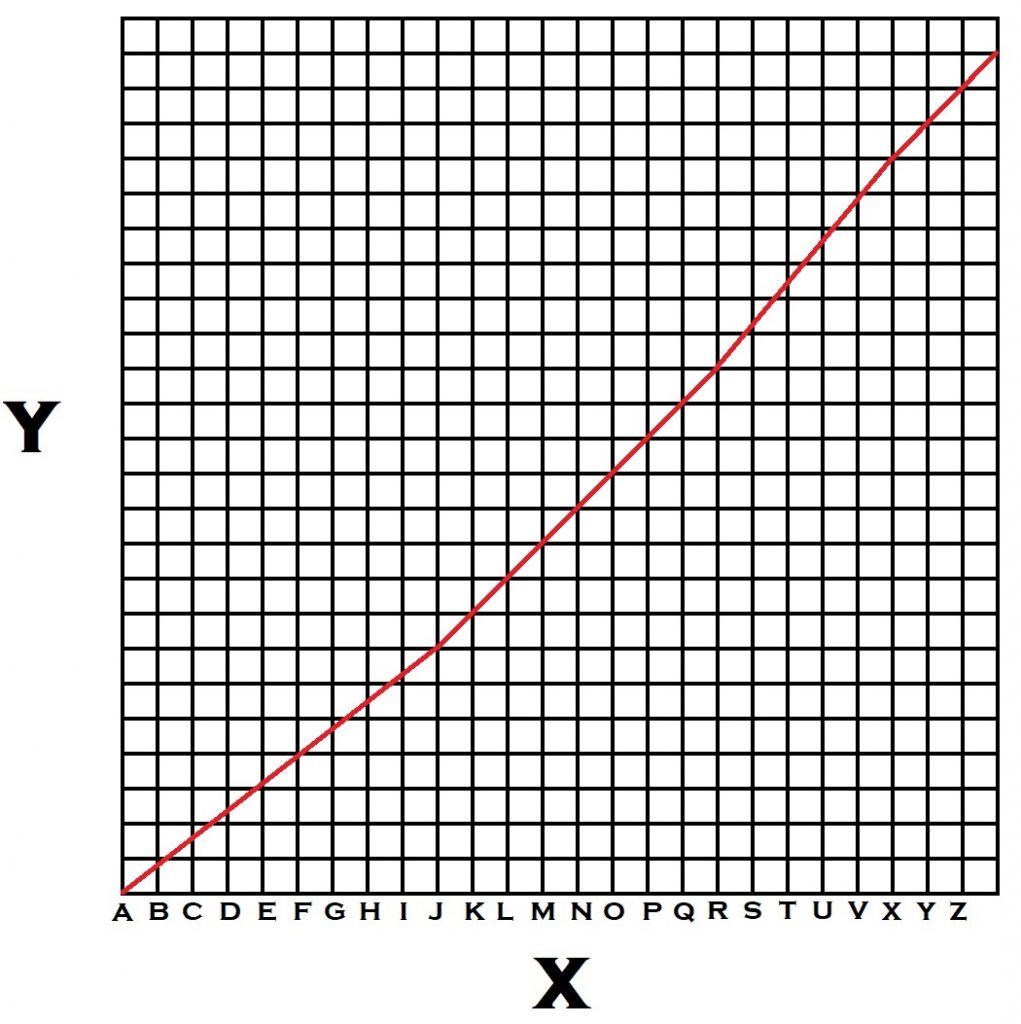

So, if we want to see our heroes overcome challenges and watch the overall tension rise… what would that look like?

Well, here’s a very bare-bones dramatic structure. We start small, and tension increases as time goes by. Low at the start, high at the end. Makes sense, right?

But… this is pretty much another straight line, right? And straight lines are pretty close to flat lines (see above). So how am I supposed to have a dramatic structure that constantly rises but isn’t a straight line?

Well, let’s think back to high school physics for a minute (sorry if this is traumatic for any of you). Did any of you ever deal with that problem of playing pool on a train? As long as the train’s moving at a steady speed, you can play a game of pool on a moving train without any weird effects. Because you, the floor, the pool table, the balls… all of it’s moving together at the same speed. We’re not aware of the speed because everything’s moving together. We don’t hit a problem until the train speeds up, slows down, or goes around a corner.

Maybe a more familiar example—if I’m driving my car at a nice, even speed, I can reach out and play with the radio. I can have a drink of water or soda or coffee. I can wiggle around and take off my jacket or get my wallet out or whatever. And it doesn’t really matter if I’m moving at 40 or 60 or even a hundred miles per hour. Going in a straight line at an even speed is just like… well, not moving at all.

Y’see, Timmy, we don’t feel a constant velocity—it’s the change that stands out. That’s what grabs our attention. When I have to hit the gas or slam on the brakes or turn fast. that’s when I’m very aware I’m on a train or in my car. And these are the moments that demand attention. These points stand out above the constant ones.

So my dramatic structure can’t be a nice, even rise like that last graph. In a good story, there’s going to be multiple challenges and my hero isn’t always going to succeed. No, really. He or she will win in the end, sure, but it’s not going to be easy getting there. There’s going to be failures, mistakes, and unexpected results. Ups and downs. Because that’s normal. We don’t want a character who’s good at everything, never has a problem dealing with anything, maybe never even encounters anything to deal with. So that line is going to be a series of peaks and drops. For every success, every time we get a little higher, there’s going to be some setbacks. Any time my characters complete a challenge, new, bigger challenge is going to appear. Hell, it might even appear before they finish the current challenge.

Still with me?

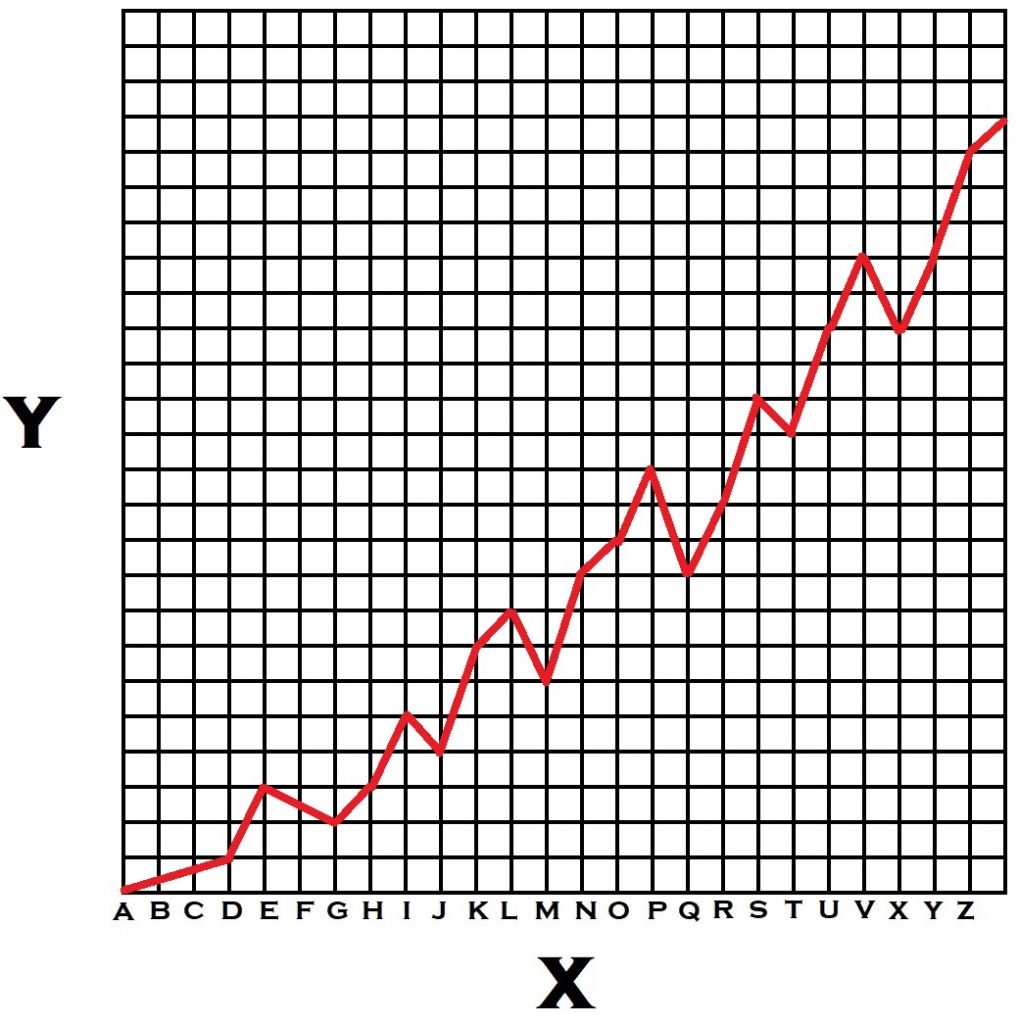

Okay then, let’s try a third graph.

So, now we’ve got peaks and valleys. Things start small, but are pretty much always rising. Also, notice how even when there are lulls or setbacks, things never go all the way back to zero. The breather we get on page 150 is not the same as the one we got back on page 16. The overall dramatic structure is that tension is rising.

This might sound like a blanket statement, but pretty much every story should look something like this graph if I map it out. I mean, they’re not all going to match up precisely peak for peak, but they should all be pretty close to this pattern. Small at the start, increase with peaks and dips, finish big.

That’s it. The easy trick to dramatic structure that Big Novel doesn’t want you to know. No matter what my narrative is doing, the tension needs to keep going up.

Simple, yes?

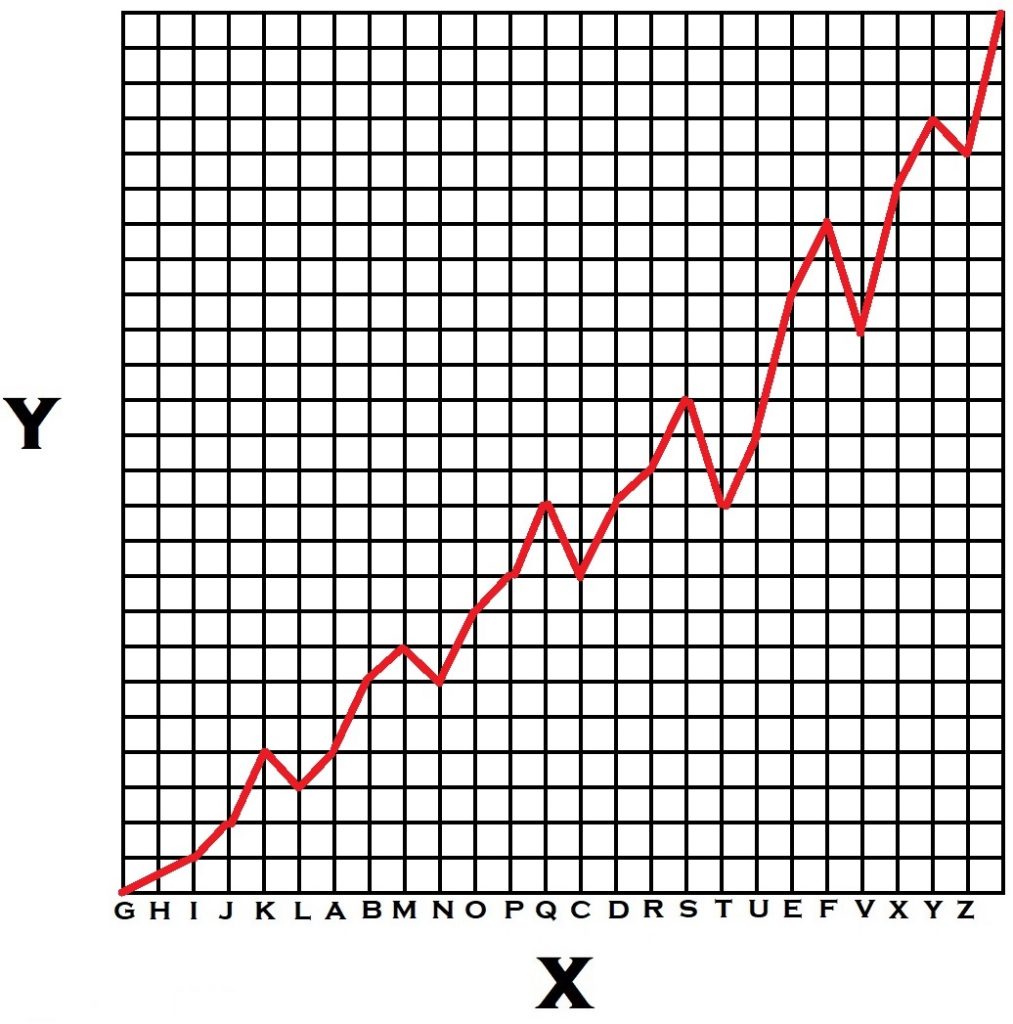

Okay now let’s take a look at another one…

Do you see what’s different about it? Looks the same at first glance, yes? But check out that bottom row. I’ve changed the narrative structure by breaking up the linear structure. There are three flashbacks in the story now. So—for the reader—the events aren’t unfolding the same way they did for the characters.

BUT… again, the overall graph still isn’t that different. For this story, the flashbacks are adding to the tension. Learning this information at this point has made the drama stronger. I’m choosing to put this plot point here in order to create a specific dramatic effect.

This is something I’ve mentioned twice or thrice here on the ranty blog. There needs to be a reason for this shift to happen at this point—a reason that continues to feed the dramatic structure. If my dramatic tension is at seven and I go into a flashback, it should take things up to seven-point-five or eight. And if it doesn’t—if it actually drops the dramatic tension to go into a flashback—why am I doing it? I shouldn’t be having a flashback right now. Not that particular one, anyway.

Now to be clear, this isn’t an automatic thing. Events E-F aren’t ten times more dramatic just because I stuck them near the end of the story instead of the beginning. This is something I need to be aware of—me, the writer—while I’m working out my narrative structure. if I map out my story like this, even in my head (and be honest about it), I can get a better sense of how well my story’s structured. I probably don’t want a super-fast, high-tension story beat right at the start of my story. A scene with no dramatic tension in it most likely shouldn’t be in my final pages. If I’ve got a chapter that’s incredibly slow, it shouldn’t be near the middle of my book.

And if I do have things like this—things that are bending that story structure waaaay out of shape—it might mean I’m doing something wrong.

Okay, I think with that I’ve thrown enough at you. Ask any questions down below. Just remember, a lot of this is going to depend on you. The other two forms of structure are pretty logical and quantifiable, but dramatic structure relies more on gut feelings and empathy with my reader. I have to understand how information’s going to be received and interpreted if I want to release that information in a way that builds tension. And that’s a lot harder to teach or explain. The best I can do is point someone in the right direction, then hope they gain some experience and figure it out for themselves.

On which note… next time, I think we’re due for another talk about Zefram Cochrane.

Until then… go write.