No, the title’s relevant. Really. Just wait.

Okay, so… we started with linear structure, and last week I went on for a bit about narrative structure. This week I want to close up my extended TED talk by discussing dramatic structure. It’s the way I weave the previous two forms together to form a killer story.

Fair warning up front—this one’s going to be the longest, so if the others strained your patience or ate into your lunch break… hey, I told you. Go hit the restroom, grab a snack, and pour yourself a drink.

Fair warning up front—this one’s going to be the longest, so if the others strained your patience or ate into your lunch break… hey, I told you. Go hit the restroom, grab a snack, and pour yourself a drink. What, now you’re drinking at work? Seriously? You might need to talk to someone.

You might recall I said that linear structure is how characters experience the story and narrative structure is how the author chooses to tell the story. In that vein, dramatic structure is how my audience receives the story. As the name implies, dramatic structure involves drama. Not in the “how shall I make Phoebe love me” sense, but in the sense that the tension and interactions in my story should almost always be building. Any story worth telling (well, the vast, overwhelming majority of them) are going to involve a series of challenges and an escalation of tension. Stakes will be raised, then raised again. More on this in a bit.

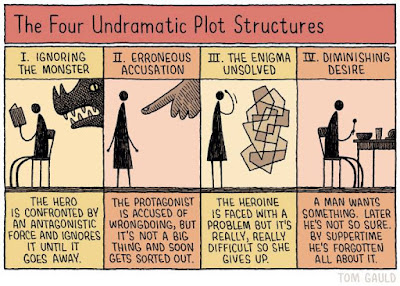

I hate getting really clinical with this stuff because… well, we’re talking about art. Not in that “ARRRRRTTTTT!!!” sense, but in that golden rule, we’ve-all-got-our-own-methods-of-doing-things way. The art part of this is personal and we should all be cautious when someone starts slapping down graphs and charts of how “good” stories go together.

But… I also think most of us here have been doing this writing thing long enough to understand that sometimes there are rules. There may be a few exceptions here and there, but that doesn’t change the fact that there are some very solid guidelines that cut across the vast majority of stories. Especially the vast majority of popular, successful stories.

That being said…

Let me show you some graphs and charts of how good stories go together.

No, don’t freak out. They’re really simple, and this is the easiest way to demonstrate the points I’m trying to make. Hell, if you’ve been following the ranty blog for any time now (or gone back and read a lot of it) you’ve probably seen them before.

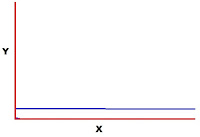

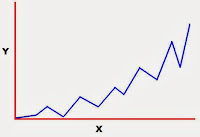

On all these graphs, X is the progression or the story from beginning to end, Y is dramatic tension, high to low. This first graph shows nothing happening. Absolutely nothing. This is me getting a good night’s sleep. From my point of view. I didn’t even have any interesting dreams. No highs, no lows, no moments that stand out. It’s flat and monotone.

Boring as hell.

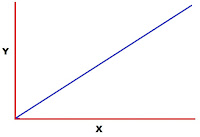

As my story progresses, I want the tension to rise. Things need to happen. Challenges need to appear and be confronted by my protagonists. By halfway through, the different elements of the story should’ve made things much more difficult for my heroes. As I close in on the end, these difficulties and stakes should be peaking.

Check this out. Here’s a bare-bones dramatic structure. We start small, and tension increases as time goes by. Low at the start, high at the end.

Mind you, these don’t need to be world-threatening challenges or huge action set pieces. If the whole goal of my story is for Phoebe to ask Yakko to the Sadie Hawkins dance without looking like an idiot, a challenge could just be finding the right clothes or picking the right moment in the day. But there needs to be something for my character to do to get that line higher and higher. There’s a movie out right now called Please Stand By where the main character’s goal is traveling to Los Angeles so she can submit her amateur Star Trek script to a screenplay contest. The challenge is that she’s kind of high on the autism spectrum, so doing something this far out of her routine is a huge deal for her.

Make sense so far?

Okay, now here are a few things we need to keep in mind.

And there are visual aids, too

First, you may have heard that “starting with action” thing that so many gurus preach. A lot of folks start with that line up around eight… and then they increasing tension. This doesn’t leave a lot of room for things to develop, but we’re hitting the ground running and going until we drop.

Thing is…when we plot this out, the line looks a lot like the one on that first graph up above. It’s pretty much just a straight line because there isn’t anywhere for things to go. And, as we established earlier, straight lines are pretty boring whether they’re set at one-point-five or at eleven. They’re monotone, and monotone is dull.

Thing is…when we plot this out, the line looks a lot like the one on that first graph up above. It’s pretty much just a straight line because there isn’t anywhere for things to go. And, as we established earlier, straight lines are pretty boring whether they’re set at one-point-five or at eleven. They’re monotone, and monotone is dull. This brings me to my second point. Dramatic structure can’t be a nice, even rise like the second graph. That’s another straight line, and straight lines are… well, you get it by this point.

Think back to high school physics for a minute. We don’t feel a constant velocity. If I’m driving a car at a nice, even speed, I can reach out and play with the radio. I can have a drink of water or soda or coffee. I can wiggle around and take off my jacket or get my wallet out or whatever. And it doesn’t really matter if I’m moving at 40 or 60 or even a hundred miles per hour.

Y’see, Timmy, we don’t notice the constant, we notice the change. That’s what grabs our attention. When I have to hit the gas or slam on the brakes or turn fast—these are the moments that grab me. These points stand out above the constant ones.

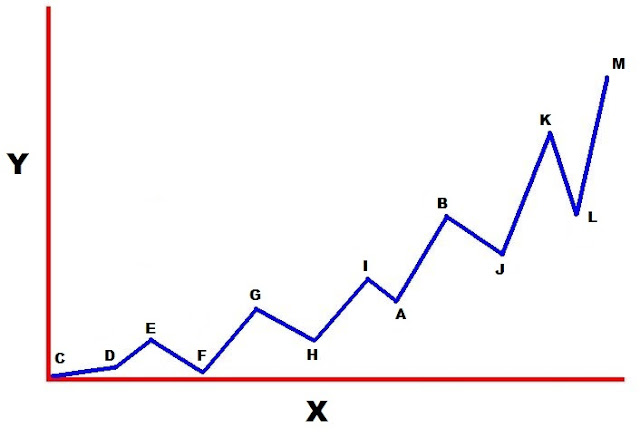

In a good story, there’s going to be multiple challenges and my hero isn’t always going to succeed. No, really. He or she will win in the end, sure, but it’s not going to be easy getting there. There’s going to be failures, mistakes, and unexpected results. Ups and downs. Because that’s normal. We don’t want a character who’s good at everything and never has a problem. So that line is going to be a series of peaks and drops. For every success, every time we get a little higher, there’s going to be some setbacks. A new, bigger challenge that appears.

Still making sense?

Good.

So, with that in mind, here’s my big graph.

Pretty much every story should look like this graph if I map it out. Not exactly peak for peak, no, but they should all be pretty close to this pattern. They’re all going to start small and grow. We’ll see tension rising and falling as challenges appear, advances are made, and setbacks occur. Small at the start, increase with peaks and dips, finish big.

That’s it. This is the big, easy trick to dramatic structure. No matter what my narrative is doing, it has to keep increasing the tension.

Simple, yes?

Keep in mind, this isn’t an automatic thing. This is something I, as the writer, need to be aware of while I craft my story. If I have a chapter that’s incredibly slow, it shouldn’t be near the end of my book. If a scene has no dramatic tension in it at all, it shouldn’t be in the final pages of my screenplay. And if it is, it means I’m doing something wrong.

Not to hammer the point, but this is what I’ve talked about a few times now. There needs to be a reason for this shift to happen at this point—a reason that continues to feed the dramatic structure. If my dramatic tension is at seven and I go into a flashback, that flashback better take it up to seven-point-five or eight. And if it doesn’t, I shouldn’t be having a flashback right now. Not that one, anyway.

See, let’s take another look at that A-B flashback up above. Even though it’s near the end of my story, it’s still pushing the story higher than everything that came before it. I’m choosing to put this information in this place in order to create a specific dramatic effect.

Think about a lot of your favorite stories. When the readers learn things affect the kind of stories they are. And that change affects the dramatic structure. Because dramatic structure tells us that things in the beginning are small, things at the end are big. Something I know at the start is automatically a minor point, but it could be a major one if it’s revealed closer to the end.

Got all this so far?

Don’t worry, we’re almost done.

There’s one last cool thing I can do with dramatic structure. It makes it easy to spot if a story is worth telling. I don’t mean that in some snarky way. The truth is, there are a lot of stories out there that just aren’t that interesting. We all know this. Since we know a good story should follow that ascending pattern of challenges and setbacks, it’s pretty easy for me to look at even the bare bones of a narrative and figure out if it fits the pattern.

For example…

I’ve read a lot of zombie books (not surprising) and seen a lot of movies. I’ve read and watched stories set in different climates, different countries, and with different reasons behind the end of the world. I’ve also seen many different types of survivors. One that crops up too often is the protagonist who decides on page seven to turn their house into a survival bunker for the thinnest of reasons. They stockpile food, weapons, ammunition, and other supplies. But twenty pages later, when the zombies finally appear out of nowhere… damn, are they ready. Utterly, completely ready. There’s no mistakes, no problems, no setbacks, because they have prepared for everything.

In other words… there’s no change. No challenge. The plot just drifts along from one incident straight to another, and the fully prepped, fully trained, and fully loaded hero is able to deal with each one with minimal effort. That’s not a story worth telling, because that story is a line.

And I’m sure you still remember my thoughts on lines…

On the flipside, some of the best zombie stories have people caught unawares, or finding their plans collapsing around them. The Undead Situation has a young protagonist who suspects the end’s coming and stocks his home… with candy and pet treats. In Fiend we find out that meth addiction makes you immune to the zombie plague… but being on meth makes it challenging to survive the zombie apocalypse. Roads Less Traveled has the protagonist work out a meticulous zombie-survival plan with her friends… which slowly unravels as people don’t follow the rules, come up short on their requirements, and generally act like, well, people.

On the flipside, some of the best zombie stories have people caught unawares, or finding their plans collapsing around them. The Undead Situation has a young protagonist who suspects the end’s coming and stocks his home… with candy and pet treats. In Fiend we find out that meth addiction makes you immune to the zombie plague… but being on meth makes it challenging to survive the zombie apocalypse. Roads Less Traveled has the protagonist work out a meticulous zombie-survival plan with her friends… which slowly unravels as people don’t follow the rules, come up short on their requirements, and generally act like, well, people. Again—dramatic structure isn’t an automatic thing. Just because I reveal something later on doesn’t guarantee it’ll be more dramatic. But if I map out my story like this, even in my head (and be honest with myself about it), I can get a better sense of how well my story’s structured.

And honestly… I think with that I’ve thrown enough at you. I wish I could offer you more. But a lot of this is going to depend on you. While the other two forms of structure are very logical and quantifiable, dramatic structure relies more on gut feelings and empathy with my reader. I have to understand how information’s going to be received and interpreted if I’m going to release that information in a way that builds tension. And that’s a lot harder to teach or explain. The best I can do is point someone in the right direction, then hope they gain some experience and figure it out for themselves.

On which note… next time I’d like to talk about getting started.

Until then… go write.