Last week I ended up finishing the editing/feedback draft of my new project (as mentioned in the newsletter), which meant I woke up Thursday morning and said “crap, I need to write a ranty blog post!” But as I started hammering away at it I quickly realized this topic wasn’t quite as quick and easy as it was in my head. So it didn’t get done Thursday. And Friday is errands. And now it’s the weekend again and okay look, I missed a week.

Anyway, I’ve talked about worldbuilding here once or thrice before, but I thought it’d be worth revisiting a certain facet of it that I talked about on Twitter a month or four back.

And that facet involves my time machine.

Well, okay, let’s back up a bit.

We’ve all read stories that revolve around some shiny-new technology. Supercomputers. Self-aware androids. Teleportation machines. Dimensional gateways. They’re the basis of so many books, comics, television shows, movies, games, and probably some other storytelling format I can’t think of. Oral tradition? Probably lots of androids in those eastern European folk tales that are verbally passed down through the generations.

I think we can all agree that having some kind of future/super technology as the basis my story is a kind of worldbuilding. If I’ve got a machine that’s going to change the world, I need to understand the machine, the world, and what kind of changes it’s going to make. So, like any type of worldbuilding, I need to have a lot of it planned out from the start. I have to be able to answer basic questions about it, because my readers will ask these questions. And they’ll ask because, by it’s very nature, we expect technology to operate in specific, predictable ways. That’s one of the things that makes it different from magic (hold your Clarke’s law responses).

And that brings us to my time machine.

If I tell you I’ve got a time machine, there’s a bunch of things we can expect people are going to want to know. For example, is the time machine real? Did you build it or just find it? No, seriously, is it real? How did you build a time machine when you can’t figure out custom ringtones on your phone?

Past those, though, there’s a bunch of things people might ask. Can you travel in time both ways, forward and back? Does the machine travel through time or does it just send you through time? If the machine travels with you, does it need some kind of energy or fuel? If it needs fuel, is there a limit to how far back/forward it can go in one trip?

And that’s before we even get into all the other bigger, standard time travel questions. What happens to the present if I change something in the past? If I know the future, can I change the future? Does the time machine compensate somehow for planetary motion?

This is a standard part of any worldbuilding. If I want to alter the world in my story somehow with a new element—for example, with a piece of technology that doesn’t exist—I need to stop and think about all the ramifications this new element is going to have. How will it change things? How will it interact with the existing world? To paraphrase Fredrick Pohl (who I think was paraphrasing someone else when he said it), a good sci-fi story doesn’t predict the car, it predicts the traffic jam.

If I, the writer, don’t know the answer to any of these basic questions, I think it tends to create problems somewhere down the road. There are two big ones, I think…

The first is general inconsistency. People use the time machine this way in chapter four, but then use it this way in chapter twelve. And, yes, we killed Hitler in 1938 but we’re… uhhhh… we’re just not going to talk about it. It’s a huge, major, historical event, but let’s, y’know, just pretend it didn’t happen. Everything turned out exactly the same anyway. Because the time machine ran out of the, uhhh, chronoline that it runs on.

See, if I don’t know the rules it’s hard for me—or my reader—to know if I’m breaking them. Which kind of means I’m cheating. It’s something I’ve talked about before—trying to world build in the third act.

The second issue is that if I don’t set any rules for how my technology works, I’m going to be trying to create tension/ conflict/ drama out of nothing. If I have no context for how the tech works, it’s hard to tell if something is difficult or dangerous or even impossible.

For example, if I say I’m using the time machine to send Wakko a million years into the past for two hours. Okay, so is that… risky? Supposed to be impossible? A normal Friday? Is there a reason it’s two hours and not three? If I don’t have any ground rules for how the tech works, I can’t tell if my characters are doing something amazing with it or not. And I can’t tell if their reactions are rational, irrational, or completely melodramatic.

Really, both of these boil down to needing context. My readers aren’t going to know how to feel about something if I don’t know how I want them to feel about it. And I can’t know unless I’ve established some sort of norm.

Look at it this way. If I tell you I’m taking a plane to Boston, you’d say “Oh, okay.” If I tell you I’m taking a plane to Cairo, Egypt, you might raise an eyebrow and say “Really?” And if I tell you I’m taking a plane to Jupiter, you might think I was nuts. Or drunk. And if I told you I was taking a plane to heaven, because heaven is up in the clouds and that’s where planes go, you might be tempted to call someone for my own safety.

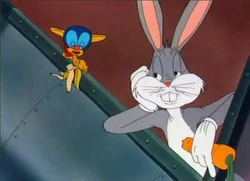

Let me give you one more. There’s an old WWII Bugs Bunny cartoon where he’s fighting a little gremlin on a plane. And after several go-rounds between them, the plane ends up in a nosedive, hurtling towards the ground as both of them scream. Fortunately, the plane runs out of gas at the last minute and ends up stopping a few feet from the ground. Laughter ensues.

All of these different statements and examples make sense because we know how planes work and how they’re generally used. It’ s pretty standard to fly cross-country, but a little unusual to fly halfway around the world. We know planes can’t fly to other planets and definitely not to the afterlife. And we absolutely know a plane isn’t going to stop moving in mid-air because it ran out of gas.

If I’m creating a new tech, I need my readers and characters to have this sort of understanding of it. Because maybe my time machine would stop in mid-air if it runs out of fuel. Or maybe it slingshots back to wherever it started. Maybe it just goes to the last destination date we gave it. Or it might just sit there until we can figure out how to channel 1.21 gigawatts into the flux capacitor.

Now, let me toss out four conditionals.

One is that I don’t need to explain everything about my time machine and how it works. Within my story, a lot of people are going to know how X works, and people usually don’t sit around talking about things they already know. Especially if they’re well-established in my world. People don’t need to have conversations about how cars work every time they go for a drive. But people in our world all understand cars well enough to know something’s wrong when the engine makes a grinding noise or fluid gushes out from beneath the hood. And something’s very unusual if the car takes off vertically and flies away. My characters should be acting and reacting in such a way that readers can tell if something’s normal or very odd or horribly wrong with how this piece of tech is working.

Two is that in my story there might be a very good reason people don’t know how my tech works, or won’t talk about how it works. Maybe they accidentally invented it just last week and are still figuring parts of it out. Maybe they’re hiding that it runs on the life-energy of kittens. Maybe it’s got some side effects they’d rather not talk about. But even then—as the writer, I should know how it works. Which means it should still act consistently.

Three is that maybe my tech isn’t doing the thing we think it’s doing. It’s not uncommon to have stories where we find out thing X is actually thing Y. My characters thought they found a time machine that projected people into the past within their lifespan, but really it just creates incredibly lifelike holograms of their own memories. Absolutely nothing wrong with this. But my characters should still have their own ideas of what the tech is doing, and there should be an understandable reason why they think this. And it should be consistent when I reveal what the tech is really doing. That’s just how a twist works.

Fourth and finally, I know somebody’s frothing at the bit to bring up Clarke’s Law, so let’s talk about it real quick. Any sufficiently advanced technology would be indistinguishable from magic. I seriously love this one (and it’s inverse, if you’re a Seventh Doctor fan). But by it’s very nature, this also excludes any such devices from this discussion. Clarke’s law literally says we can’t recognize X as technology. So we shouldn’t expect to follow tech rules while we’re writing about it.

Anyway, I’ve been blabbing on about this for a while now and I think you’ve got the idea. If I want to make a time machine– or a teleporter, a psychokinesis drug, cybernetic eyes, bio-booster armor, whatever– I need to have consistent, thought-out rules for how this technology works. And these rules need to be in place on page one. If I’m not going to even think about how time travel in the past affects the present until I’m 2/3 done with my book… I’m probably going to hit some snags.

Next time, I want to talk about Neil Armstrong’s left foot.

No, wait. Your left foot! That’s what we’re going to talk about!

Until then, go write.