As always, if you don’t get the title… your pop-culture kung fu is weak.

So, last summer a movie came out some of you may have seen called Hancock, written by Vincent Ngo and Vince Gilligan. Apparently the lead actor was in one or two other films, as well, and had a small fan following that helped a bit at the box office. I got to review it for the CS Weekly newsletter (sign up over there on the right—it’s free), and it’s what first got me thinking about this week’s topic. It came up again a few months ago over lunch with a friend of mine who’s written a few movies (and a television show I know at least one of you loved). And it’s something I had to think about a lot for my forthcoming book, Ex-Heroes.

And I thought it’d be worth bringing up here for two or three of you (almost a full quarter of the ranty blog’s readership).

When you’re playing in the genre realms, you should note there’s a very big difference between a story about a superhero and a story about someone who has superpowers. They’re not the same thing, and trying to cram one into the mold of the other will almost always cause problems.

If you think about it, stories about people with superhuman abilities have been around for thousands of years. Gilgamesh and Hercules both had superpowers. So did Anubis, Icarus, the Green Knight, and yes, even Jesus. In the classics there’s Matthew Maule, Dr. Jekyll, and even arguably the Count of Monte Cristo. There are lots of modern-day stories and films featuring people with superhuman abilities, too. The Dead Zone is about a person with superpowers. So are the Sixth Sense, Scanners, and Unbreakable. Heck, even Luke Skywalker has abilities far beyond those of mortal men (and Wookies).

However… are any of these characters superheroes?

Let’s look at a few side by side examples.

The X-Men comic books and films had characters who could control flames, read minds, and teleport. However, so did Stephen King’s novel Firestarter, Alexander Key’s Escape to Witch Mountain, and Steven Gould’s Jumper.

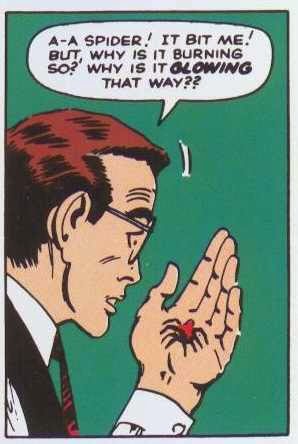

Spider-Man is a character who gets abilities when his DNA is mixed with an insect (okay, an arachnid) during a science experiment. But this is also what happens in both versions of The Fly. Spider-Man also has strength and agility far beyond that of normal men, just like John Carter of Mars in the books by Edgar Rice Burroughs.

In the Fantastic Four comics and films, Susan Richards nee Storm can turn invisible, but so could the Greek hero Perseus, Darien Fawkes in the Sci-Fi Channel series The Invisible Man, and John Griffin in its H.G. Wells namesake novel.

Batman is a guy who hides his identity, gears up, and goes out at night to fight crime in order to avenge the loss of his loved ones– just like Charles Bronson in Deathwish.

Now, if I had to nail down what the difference is, I would say that a super hero story is defined by a person who makes a conscious decision to publicly use their powers for the greater good (a wider, broader goal that does not involve them). They aren’t doing it to get even, to save someone close to them, or to show off. Most of them feel morally compelled to use their abilities this way, no matter how crappy it makes other aspects of their lives. Obvious as it may sound—superheroes act heroically.

This public nature also means they deal with public sentiment of one kind or another. Captain America is venerated as a historical figure. Superman is lauded in the press. Batman and Spider-Man receive mixed reviews. The X-Men are openly considered criminals (or were, last time I read their books—they may have Congressional Medals of Honor at this point).

I would also go so far as to say a costume is almost necessary, much in the same way a cowboy needs a hat and a horse. However, I’ll also toss out the proviso that the costume in and of itself does not make a story a superhero story, just as the hat and horse do not automatically make something a western.

The flipside of this is a super powers story. Someone who may have superhuman abilities, but all their motivation is usually personal, and their actions tend to be more behind-the-scenes. I listed a few examples of this above, side by side with their comic book counterparts. In The Dead Zone (the original book/ movie) Johnny is acting for the greater good, but he’s taking very secretive steps. In Jumper, David’s really just interested in saving himself and his girlfriend. Harry Potter is all about hiding your powers and staying apart from the world. And in Hancock, while he is acting publicly, the story itself is really all about his disconnect with humanity, not that he can fly and throw cars around. If you think about it, the story of Hancock works almost exactly the same if he’s just a powerless, homeless vigilante with amnesia.

Also on that flipside, superpowers stories involve street clothes. Even if someone has a “uniform” of some sort (John Constantine almost always dresses the same way) it tends to be boots, tee-shirts, and other things that wouldn’t look that out of place on a city street.

I also think a lot of this difference has to do with the setting for these stories. More often than not, a superpowers story has a very realistic setting. Aside from a very limited, few beings, there’s almost nothing to distinguish it from the real, day-to-day world we hear about each weeknight from Charlie Gibson and ABC News.

By contrast, look at the settings for some of our well-known superheroes. Spider-Man is a common sight swinging through his version of New York, a place where the Fantastic Four and Avengers have very public office buildings and the existence of aliens—several types of aliens– is a well-documented fact. Superman’s a known alien, too. Hellboy’s an actual demon (arguably the Antichrist) who’s gone straight and publicly works for the U.S. government.

Once you can tell them apart, I think one of the immediate problems with pushing a superpowers story into a superhero mold is the silliness factor. When someone puts on a costume in a real world setting, it suddenly feels like the writer isn’t taking things seriously. Check out a little indie film called Sidekick. It has a few flaws, but once the hero pulls on a costume in the third act (in the middle of rescuing his would-be girlfriend from a mentally unbalanced kidnapper) the audience just can’t forgive it. What would people have thought if the film version of Firestarter ended with little Drew Barrymore pulling on red tights and a cape to go fight evil as Firegirl or some such?

(Please keep in mind before answering, we’re talking about a nine-year old Drew Barrymore in spandex, not grown-up Drew. Perverts.)

You get similar issues going the other way. While the problems Peter Parker deals with because of his powers are interesting, when someone picks up the latest Amazing Spider-Man they want to see him pull on the webbed suit and fight the Lizard. Too much melodrama in street clothes with Aunt May and J. Jonah Jameson just starts to get dull (as Marvel’s sales figures over the past few years can attest to). There’s a reason the folks who read the daily Spidey strips in the newspaper also tended to skip Mark Trail and Mary Worth. People who read superhero stories aren’t looking for stark realism.

As a fun aside, some of you may remember an experiment Marvel tried years back called the New Universe. They were comics about real people in the real world who developed superpowers and reacted… well, realistically. Many of them tried to hide their new abilities, several tried to get rid of them, and more than a few were corrupted by these powers. The whole line sold horribly (so much so that I became a regular contributor to one of the letter columns with no effort) and was cancelled after barely two years—the end of which involved several attempts to turn the characters into true superheroes.

I’ve also noticed that superpowers stories tend to brush over the origin with a simple “this is the way it is,” sort of explanation. In both Jumper and the Harry Potter books, we’re just told that this is the way the world has always been. Some folks get the teleport gene. Some can do magic (why some can and some can’t is never explained, but it also seems to be genetic in J.K.’s books, too). Also superpowers stories, if they have to give an origin, tend to lean toward the hard sciences, making it as believable as possible.

With superheroes, though, the origin is almost a standard. A writer can also get away with somewhat sillier, non-scientific origin stories. The Flash was struck by lightning. More than a few characters have gotten superpowers from blood transfusions (including one of my own). Radiation is a common source of superhuman abilities, too, despite what we learned in seventh grade science. Remember how the Hulk got his powers? No, not the recent version—the original version. Mild-mannered Bruce Banner was near the prototype gamma bomb when it was detonated and received a massive dose of radiation. Yes, a mere 45 years ago, Stan Lee wrote a story where someone got their powers by standing next to a nuclear bomb when it went off. Yet here we are today and that is still the accepted origin of the Incredible Hulk (although they’ve oh-so-casually moved him a bit further from ground zero).

One last, related note– the abilities in superpowers stories tend to be a bit more plausible and limited. Jean Gray of the X-Men can alter matter on a molecular level with her telekinetic abilities, but Tony and Tia Castaway need the mental crutch of a harmonica just to move around a hat rack with a raincoat on it. In fact, the only two superpower stories I can think of where someone has overwhelming powers would be the film Dark City and Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel The Lathe of Heaven.

Wow, have I rattled on about this or what? I’m sure you’ve all got other stuff you need to go do. Like writing stuff.

Next time… well, next time I think we finally need to talk about some of these issues with your mother.

But until then, go write.

Superpowers stories involve street clothes. Even if someone has a “uniform” way of dressing, it tends to be suits, boots, leather jackets, and other things that wouldn’t look that out of place on a city street. Hercules didn’t have a special outfit for performing the twelve labors. Carrie doesn’t duck out of her prom to put on a leotard and a domino mask. On Grimm, Nick tends to just dress like a police detective, even when he knows he’s going up against Wesen or other monsters.

Superpowers stories involve street clothes. Even if someone has a “uniform” way of dressing, it tends to be suits, boots, leather jackets, and other things that wouldn’t look that out of place on a city street. Hercules didn’t have a special outfit for performing the twelve labors. Carrie doesn’t duck out of her prom to put on a leotard and a domino mask. On Grimm, Nick tends to just dress like a police detective, even when he knows he’s going up against Wesen or other monsters.