Trying something a little new with the formatting here. Please make your comments/ thanks/ complaints in the space down below.

Anyway, looking at the calendar, it’s getting to that season where I blather on about superheroes again.

Or maybe superpowers.

Or both. They’re kinda related after all.

As some of the book covers displayed on this page suggest, superheroes are kinda my jam. Have been for years and years now. I wouldn’t claim to be an expert on the subject, but I feel safe saying my knowledge level is in the higher percentiles. I thought about these stories a lot as a kid growing up and, in a way, even more since I’ve moved into this odd career of “professional storyteller.” It’s a topic I can blather on about a lot.

As I’m about to demonstrate…

One thing I’ve noticed in some corners is a bad habit people have of labeling a lot of things “superhero” stories, because that title carries a lot of weight. About twenty billion dollars worth, if we go off the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Not exactly a bad weight to have hanging on your shoulders.

But…

I think it’s worth noting that there are a lot of differences between a superhero story and a story about people with superpowers. They are not the same thing. Not remotely. And if I try to do one while using the devices and tropes of another… well, I’m going to mess with people’s expectations. Which usually leads to a disappointed audience.

Now, granted, none of what I’m spouting here is formal rules set down by tenured professors or doctoral candidates. If we just look at a lot of fiction, though, we’ll see that this idea’s been around for ages. Superhero stories and superpowers stories have always been two very different animals.

So, what are some of those differences?

Let’s break ‘em down…

First off, superpowers do not automatically equal superheroes. We can all agree on that, right? Carrie. Blackbirds. Limitless. Girl Like A Bomb. Glass. Stranger Things. All of these stories feature people with superhuman abilities.

But are any of these superhero stories? Not really. Just having some sort of superpower doesn’t automatically make someone heroic. Heck, in a couple of those stories the person with the powers is arguably the villain.

And that brings me to my second point (one of the big ones). Heroics depend very much on motivation. The same action can be heroic in one situation, almost cowardly or bully-ish in another. Or maybe it’s just an action. We all do things on a daily basis that are personally motivated, and maybe even a bit challenging, but it doesn’t make them heroic, right? A superhero story’s almost always defined by a character who makes a conscious decision to use their powers for a wider goal that may not benefit them (and often doesn’t). Obvious as it may sound… superheroes act heroically.

And just to be clear, when I’m speaking about heroic actions… Don’t confuse heroic actions (i.e. actions that are brave and selfless and pure of heart) with the actions of our hero (i.e. actions taken by the protagonist). Just because he or she’s the hero of the story doesn’t mean all their actions are automatically heroic. Make sense?

Good.

When we read stories about super-powered folks, though, they’re almost always more personal and intimate. Dare I say… a little selfish. In these stories, people are doing things much more for themselves than for any sort of greater good. It’s not that they’re evil, it’s just that the plot concerns them first and maybe the world second or third. If at all.

When we read stories about super-powered folks, though, they’re almost always more personal and intimate. Dare I say… a little selfish. In these stories, people are doing things much more for themselves than for any sort of greater good. It’s not that they’re evil, it’s just that the plot concerns them first and maybe the world second or third. If at all.

Another common point of confusion here is doing the right thing for the wrong reason. Is Yakko taking down the bad guy because it’s the right thing to do… or just to get revenge? Is Dot stopping the bomb to save thousands of innocents… or just to save her friends who are handcuffed to it? Is Wakko fighting the Automata Society to end their reign of terror… or just so they’ll stop coming after him?

A third point (strongly related to the last one) is that superhero stories tend to be about public use of powers and abilities. They’re about people who’ve decided to use their abilities to help others, and they get seen doing it. This public nature also means they deal with public reactions of one kind or another. Sometimes they’re loved, sometimes they’re feared and hated.

I’ll note a lot of stories that are just about folks with superpowers tend to involve hiding abilities. Keeping things secret from the world at large. In the same way their motives are personal, their actions tend to be a lot more low-key and behind the scenes. In fact, when abilities get revealed in a superpowers story, it’s almost always a cause for panic.

That flows nicely into point number four. The abilities in superhero stories tend to be much more extreme. Phoebe’s not just strong, she’s throwing-cars-down-the-street strong. Wakko doesn’t just move things with his mind, he can throw cars down the street with his mind. Dot doesn’t just start fires, she can throw fireballs that blast cars down the street.

That flows nicely into point number four. The abilities in superhero stories tend to be much more extreme. Phoebe’s not just strong, she’s throwing-cars-down-the-street strong. Wakko doesn’t just move things with his mind, he can throw cars down the street with his mind. Dot doesn’t just start fires, she can throw fireballs that blast cars down the street.

You get the point. Superhero stories involve throwing a lot of cars around.

But when a story’s just about someone with superpowers, we tend to see a lot more limits on those abilities. Not always (Dark City and The Lathe of Heaven come to mind), but most of the time they seem to be much more grounded in reality. A little easier to rationalize, at least. Side effects and odd handicaps are much more common.

And for our fifth and final point, let’s talk about the elephant in the superhero room. The costume. The outfit that hides our hero’s secret identity from the world.

I wouldn’t say a costume/ secret identity is absolutely necessary, but I do think it creates a lot of odd situations in my story if there isn’t one. If everyone knows who Yakko is, then they know who Yakko’s friends and family are. They can find out where he lives and shops and eats. If he’s not using a secret identity, he’s either aiming for a very solitary life or he’s painting a lot of targets on people and places.

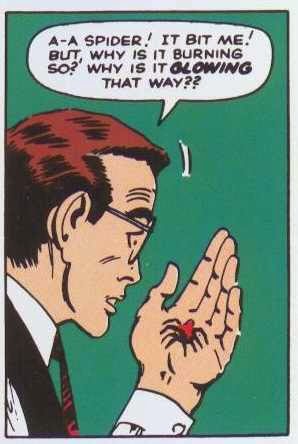

One other aspect of this a friend of mine once brought up (he’s one of the writers on the new Pet Semetary movie (shameless plug)) is that a superhero often becomes an identity unto themselves. They’re iconic symbols, and not necessarily tied to the people who first created them. Spider-Man, Batman, Ms. Marvel, Superman, Captain America, the Flash… all of these superhero identites have had multiple people behind them.

One other aspect of this a friend of mine once brought up (he’s one of the writers on the new Pet Semetary movie (shameless plug)) is that a superhero often becomes an identity unto themselves. They’re iconic symbols, and not necessarily tied to the people who first created them. Spider-Man, Batman, Ms. Marvel, Superman, Captain America, the Flash… all of these superhero identites have had multiple people behind them.

Compare all of that to a story about superpowers, where secret identities almost never come up because… well, like I mentioned in point three, nobody knows about them. I don’t have to hide my identity when I teleport because I do everything I can to make sure nobody finds out I can teleport. So the people in these stories tend to wear… well, street clothes. They never duck into a phone booth to change before using their powers in public because—again—they almost never use their powers in public.

Okay, for our sixth and final-for-reals-now point, let me add this. The setting matters a lot in these stories, too. If I’m just telling a story about superpowers, they’re almost always set in the real world. Or, at least, a world indistinguishable from the real world to the casual viewer. Because if they weren’t, it’d imply having superpowers wasn’t that impressive. Being telepathic in the sci-fi world of the Federation—a coalition of hundreds of alien races with unique abilities– is checking a box on a recruitment form. Being telepathic in a documentary about 1940’s Paris, though… that’s freakin’ amazing.

Superhero stories, though, tend to take place in worlds that are already fantastic. They’re already pre-loaded with amazing things. Consider the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Aliens are real and publicly known. Magic is real and publicly known. Cyborgs. Androids. Inhumans. Demons. People fly! Lots of people! This is not the world outside anyone’s window.

Now, again, this is not a set of iron-clad guidelines. I have not defended my thesis or gone through rigorous peer review. This is just forty-odd years of observation paired with forty-odd years of thinking about how stories are told. And, as I often say, there’s always going to be exceptions. So if I’ve got a superhero who doesn’t wear a costume or a super-powered person who’s acting very heroically, it doesn’t mean my whole story’s about to collapse.

But maybe I should run my story of super-powered beings through this list and just see what side of things they fall on. Does most of it line up with the kind of story I want to tell? Is the label I’m putting on it—and the expectations that label will bring—going to match up with what my story delivers?

Because if it doesn’t… maybe I’m writing the wrong thing.

Next time, I’d like to quickly revisit an old favorite before heading off to Wondercon for the weekend.

Until then… go write!