It’s not a pop culture reference, don’t worry…

I haven’t talked about characters for a while, so I figured we were due.

In my opinion, character can be broken down into two sets of three. I talked about

the first set a while back, and I’ve mentioned the individual elements on and off since then. The second set is kind of a new idea here at the ranty blog, although you’ll probably see some connections with other things I’ve blathered on about.

The first set is all about hard facts. This is

character sketch stuff that may or may not come up in my actual story, but it’s still important for me to know as a writer. If I want Phoebe to be a good character, there are three traits she has to have.

Firstand foremost, a character needs to be

believable. It doesn’t matter if said character is man, woman, child, lizard man, ninja, superhero, or

supervillain. If my reader can’t believe in the character within the established setting, my story’s got an uphill battle going right from the start.

Phoebe has to have

natural dialogue. It can’t be stilted or forced, and it can’t feel like she’s just spouting out

my opinions or beliefs. The words have to flow naturally and they have to be the kind of words Phoebe would use. I’ve seen countless stories where soldiers talk like school kids or high school jocks talk like Oxford professors.

The same goes for Phoebe’s actions and

motives. There has to be a believable reason she does the things she does. A real reason, one that makes sense with everything we know about her,

or will come to know. If a characters motivations are just there to push the plot along, my readers are going to pick up on that really quick.

Also, please keep in mind that just because a character is based on a real person who went through true events does not automatically make said character believable. I’ve talked here many, many times about

the difference between real-real and fiction-real, and it’s where many would-be writers stumble. Remember, there is no such thing as an “unbelievable true story,” only an unbelievable story.

The

second trait, tied closely to the first, is that Phoebe needs to be

relatable. As readers, we get absorbed in a character’s life when we can tie it to elements of our own. We enjoy seeing similarities between characters and ourselves so we can make extended parallels with what happens in their lives and what we’d

liketo happen (or be able to happen) in our own lives.

Taken is about a father trying to reconnect with his somewhat-estranged daughter. The Harry Potter books are about a kid whose adoptive family dislikes him for being different.

Grimm is about an up-and coming police detective whose getting ready to propose to his girlfriend. There’s a reason so many movies, television shows, and novels are based on the idea of ordinary people caught up in amazing situations.

Some of this goes back to the idea of being on the same terms as your audience and also of having a general idea of that audience’s common knowledge. There needs to be

something they can connect with. Many of us have been the victims of a bad break up or two. Very, very few of us (hopefully) have hunted down said ex for a prolonged revenge-torture sequence in a backwoods cabin. The less common a character element is, the less likely it is your readers will be able to identify with it. If your character has nothing but uncommon or rare traits, they’re unrelatable. If Phoebe is a billionaire heiress ninja who only speaks in either Cockney rhyming slang or an obscure Croatian dialect and lives by the code of ethics set down by her druidic cult… how the heck does anyone identify with that? And if readers can’t identify with Phoebe, how are they going to be affected by what happens to her?

That brings us to the third point, a good character needs to be likeable. Not necessarily pleasant or decent, but as readers we must want to follow this character through the story. Just as there needs to be some elements to Phoebe we can relate to, there also have to be elements we admire and maybe even envy a bit. If she’s morally reprehensible, a drunken jackass, or just plain uninteresting, no one’s going to want to go through a few hundred pages of her exploits… or lack thereof.

Again, this doesn’t mean a good character has to be a saint,

or even a good person. Leon the Professional is a brutal hit man.

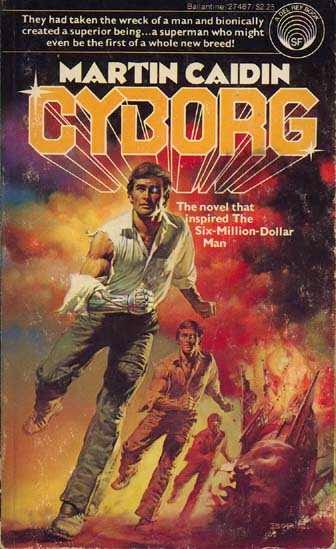

Cyrus V. Sinclairaspires to being a sociopath. Barney Stinson is a shameless womanizer. Hannibal Lecter is a serial killer with some horrific dietary preferences. Yet in all of these cases, we’re still interested in them as characters and are willing to follow them through the story.

A good character should be someone we’d like to be, at least for a little while. That’s what great fiction is, after all. It’s when we let ourselves get immersed in someone else’s life. So it has to be a person–and a life– we want to sink into.

Now, I’m sure anyone reading this can list off a few dozen examples from books and movies of characters that only have one or two of these traits. It’d be silly for me to deny this. I think you’ll find, however, the people that don’t have all three of these traits are usually

supporting characters. They don’t need all three of these traits because they aren’t the focus of our attention. If I’m a halfway decent writer, I’m not going to waste my time and word count on a minor character—I’m going to save them for Phoebe.

So, that’s the first set of three.

The second set of three is about putting all that information into my story. Y’see, Timmy, it’s not enough just to have the above character elements. They need to be established in the story in a natural, organic way.

Let’s talk about the three main ways of doing that.

Firstis the easy one—characters establish themselves through their own words and actions. I’ve mentioned before that how someone talks is very important, as well as what they talk about. If all Phoebe talks about is work, that tells us something about her. If every conversation she has leads to talking about sex, that gives us a different bit of insight. If she speaks with precise grammar it implies something about her, just like it does if she talks like a stoned surfer, or if she rarely talks at all. If I show Phoebe kicking an alley cat on her way home from work, this says a lot about her character. On the other hand, if the reader sees her giving the raggedy cat a can of tuna and some attention, it says something else (depending on

when it happens in the story).

Second is the way other characters talk about them and react to them. If Phoebe is talking in a calm, measured voice but her employees are nervous—or even terrified—that’s a big clue in to what kind of person they know she is. Likewise, if she’s trying to ream someone out over their poor job performance and they’re ignoring her, that also tells us something. A lot of my characters are going to know each other

better than the audience does, and their interactions are going to be a big hint to the reader as to what kind of person Phoebe is.

And thirdis how their words and actions jibe with the reader’s personal experience. Remember above how I mentioned Phoebe turning every conversation to sex? Well if that’s the case, but we also see her go home alone every night, that’s telling us something insightful about her. If she tells the guy at the bar that she loves animals but then throws something at that cat, it gives us a much better idea about who she is. And if she absolutely assures somebody that she can be trusted after we’ve seen her screw three other people over, well… As many folks have said, actions speak louder than words. So when there’s a contrast or an open contradiction, this can be a great way to get across major character elements.

Two sets of three. Look over some of your characters and see where they match up, and with which sets.

Next time, I’d like to step outside of the usual topics here and talk about why people I’ve slept with generally rate higher than other people.

Until then, go write.

An example I’ve used before is when a ninja leaps out of the shadows to attack me. On the one hand, I want to mention the mask and the gloves and the sash belt and those special shoes that ninjas wear. Plus maybe they’ve got weapons in their hands or tucked in their belt or strapped to their back. Maybe even cursed weapons with extra barbs or weird auras. And wait… is that long red hair? Is this ninja a woman? Holy crap, the robes are kinda loose but, yeah, I think she is.

An example I’ve used before is when a ninja leaps out of the shadows to attack me. On the one hand, I want to mention the mask and the gloves and the sash belt and those special shoes that ninjas wear. Plus maybe they’ve got weapons in their hands or tucked in their belt or strapped to their back. Maybe even cursed weapons with extra barbs or weird auras. And wait… is that long red hair? Is this ninja a woman? Holy crap, the robes are kinda loose but, yeah, I think she is.

The worst of all of these has to be the introspective moment. That point when the arrows are flying and plasma bolts are crashing around us and my character pauses to dwell on how fragile the connections are between all of us, and the series of decisions that unknowingly brought him to this moment. And this place. Of all the possible places he could’ve been right now. One different choice and maybe he’d be on a date with that cute barista, instead of here, pondering the threads of destiny…

The worst of all of these has to be the introspective moment. That point when the arrows are flying and plasma bolts are crashing around us and my character pauses to dwell on how fragile the connections are between all of us, and the series of decisions that unknowingly brought him to this moment. And this place. Of all the possible places he could’ve been right now. One different choice and maybe he’d be on a date with that cute barista, instead of here, pondering the threads of destiny…  And speaking of action and doing things… have I mentioned that my new book, Terminus, comes out next week? Like, one week from today. It’s an Audible exclusive, and if you wanted to preorder it now that’d help further convince the people who pay me that my books are a good investment. Which mean more books down the line. Which means we all win.

And speaking of action and doing things… have I mentioned that my new book, Terminus, comes out next week? Like, one week from today. It’s an Audible exclusive, and if you wanted to preorder it now that’d help further convince the people who pay me that my books are a good investment. Which mean more books down the line. Which means we all win.