No, no… don’t rush to answer that. I’m pretty sure I can guess how most of the comments section would go.

However…it is an important question, whether I’m writing books or screenplays. The folks who just bought my new Lovecraftian techno-thriller aren’t expecting a long lesson about how memes work. If I’m billing myself as the next Dan Brown, the clue “man’s best friend” better not leave half a dozen codebreakers baffled as to what the three letter password is for the doomsday device. Heck, even if I’m hired to pen the next Pokemon movie, I probably shouldn’t spend a lot of screen time explaining all the medical reasons why little kids shouldn’t drink paint.

Cause let’s face it—nobody likes to be called stupid. Not even kids. Heck, especially not stupid people. We all hate being condescended to and having things spoon-fed to us at a crawl. We get angry about it. At best we get frustrated with the person throttling the speed we can absorb things at.

So, having established that nobody likes being considered an idiot, it stands to reason most people like to feel smart, right? And that includes my readers. I want them to like my stories, not feel angry or frustrated because of them.

But a lot of stories assume readers

are stupid. They spell everything out in painful detail. They drag things out. They repeat things

again and again and again. These authors think their readers won’t know or understand or remember anything, and they write their stories accordingly.

So here’s a few easy things I try to do so my readers feel smart and they’ll love my stories…

I know what my audience knows

I’ve talked a couple times here about empathy and

common knowledge. It’s stuff I can feel safe assuming everyone knows. Grass needs water and sunlight to grow. Captain

Americais a superhero. Nazis are still the bad guys. Maybe you noticed that a few paragraphs back I rattled off

Lovecraftian,

Dan Brown, and

Pokemonwithout bothering to explain any of them. I know the folks reading this would have—at the very least—an awareness of these words and names. Knowing what my specific audience knows is an important part of making them feel smart, because this is what lets me judge what they’ll be able to figure out on their own.

This goes for things within my story, too. Yeah, odds are nobody’s ever heard the term Caretaker used precisely the way I use it in

Dead Moon, but I don’t have to keep explaining it. I can make a couple references at the start and then just trust that

my readers will remember things as the story goes on. It’s a completely made up word, but I bet most of you know what a Horcurx is. Or a TARDIS. Or a Mandalorian. They don’t need to be explained to you again and again.

I try to be smarter than my audience

There’s an agent I’ve referenced here, once or thrice, Esmund Harmsworth. I got to hear him speak at a writing conference years ago and he pointed out most editors will toss a mystery manuscript if they can figure out who the murderer is before the hero does.

Really, though, this is how it works for

any sort of puzzle or intellectual challenge in a piece of writing. If I’ve dumbed things down to the point of simplicity—or further—who’d have the patience to read it? It’ll grate on their nerves, and it makes us impatient when we have to wait for characters to figure out what we knew twenty minutes ago.

I don’t state the obvious

Michael Crichton got a very early piece of writing advice that he shared in one of his books. “Be very careful using the word obvious. If something really isobvious, you don’t need to use it. If it isn’t obvious, than you’re being condescending to the reader by using it.”

Of course, this goes beyond just the word obvious. Revisiting that first tip up above, should I be wasting half a page telling my readers Nazis were bad? When Yakko staggers into a room with

three knives in his back just before collapsing into a puddle of his own blood, do I need to tell anyone that’s he’s seriously hurt? I mean,

you all got that, right?

I take a step back

When something does need to be described or explained, I think our first instinct is to scribble out all of it. We want to show that we thought this out all the way. So we put down every fact and detail and nuance.

I usually don’t have to, though. I tend to look at most of those explanatory scenes and cut it back 15 or 20%.

I know if I take my audience most of the way there, they’ll probably be able to go

the rest of the way on their own. People tend to fill in a lot of blanks and

create their own images anyway, so getting excessive with this sort of thing rarely helps.

I give them the benefit of the doubt

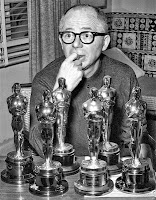

This is the above tip, but the gap’s just a little bigger. Three-time Academy-Award-winning screenwriter Billy Wilder said if you let the audience add 2+2 for themselves now and then, they’ll love you forever. That’s true for writers of all forms. Every now and then, just trust they’ll get it. Not all the time, but every now and then I just make a leap of faith my audience can make a connection with almost no help whatsoever from me. Odds are that leap isn’t as big as you think it is.

Y’see, Timmy, when I spell out everything for my audience, what I’m really telling them is “I know you won’t be able to figure this out on your own.” My characters might not be saying it out loud, but the message is there. You’re too stupid for this—let me explain.

And that’s not going to win me a lot of return readers.

Hey, next week is Thanksgiving here in the U.S. and my parents are coming to visit for the holidays and hahhaaaha I’m not stressing about it YOU’RE STRESSING HOW IS IT THE END OF NOVEMBER ALREADY OH CRAP

…sorry, that was a typo. What I meant to say was it’s Thanksgiving so I’ll probably just do something quick on Tuesday or Wednesday. And after that… well, if you’ve been following the ranty blog for any amount of time you know what I’ll be talking about on the day after Thanksgiving.

Until then, go write.

This goes for things within my story, too. Yeah, odds are nobody’s ever heard the term Caretaker used precisely the way I use it in Dead Moon, but I don’t have to keep explaining it. I can make a couple references at the start and then just trust that my readers will remember things as the story goes on. It’s a completely made up word, but I bet most of you know what a Horcurx is. Or a TARDIS. Or a Mandalorian. They don’t need to be explained to you again and again.

This goes for things within my story, too. Yeah, odds are nobody’s ever heard the term Caretaker used precisely the way I use it in Dead Moon, but I don’t have to keep explaining it. I can make a couple references at the start and then just trust that my readers will remember things as the story goes on. It’s a completely made up word, but I bet most of you know what a Horcurx is. Or a TARDIS. Or a Mandalorian. They don’t need to be explained to you again and again.