If you’ve been reading the ranty writing blog for a while, you may have picked up that I’m not a big fan of focusing on ART. And I’m even less of a fan of people who start to talk about ART in very lofty terms. Especially when they get dismissive of people who aren’t trying to make ART.

Just to be clear, I’m not talking about art. Writing is an art, yeah, and I’m a big believer in that. I’m referring to those folks who go on and on about the ART of writing. You know the ones I’m talking about. Those people who really believe in the ART over all things.

Now, full disclosure, part of this may be a reaction to a writing TA who berated me in front of the class my junior year of college because I wanted to write, well… fun stories. Stories that entertained people. Said TA basically shredded the story I was working on (a sci-fi horror thing about a government teleportation experiment that went wrong) and told me in no uncertain terms, that if I wasn’t trying to CHANGE PEOPLE’S LIVES with my writing, then I was just WASTING everyone’s time!

Anyway…

As it happens, a year before that fateful class, I’d been studying early American literature and my class discussed Wieland by Charles Brockden Brown, first published in 1798. It’s considered an early American classic, the first noteworthy American novel, and its author died penniless and drunk in a snowbank. Story is, his own mother wouldn’t even buy his books. Seriously. He was pretty much unknown during his lifetime outside of a small circle (which shrank rapidly after his death) and it wasn’t until the 1920’s that he became semi-known and retroactively entered into the canon of literature.

Well, I decided to be bold and asked my professor about this. Why was the book being considered literature now? I mean, it’d failed back then, barely anyone knew about it today, so how does it qualify? If it was actually great, we wouldn’t need to be told that it was great, we’d already know, right? Why should we consider it relevant now when the author’s own mother didn’t even consider it relevant then?

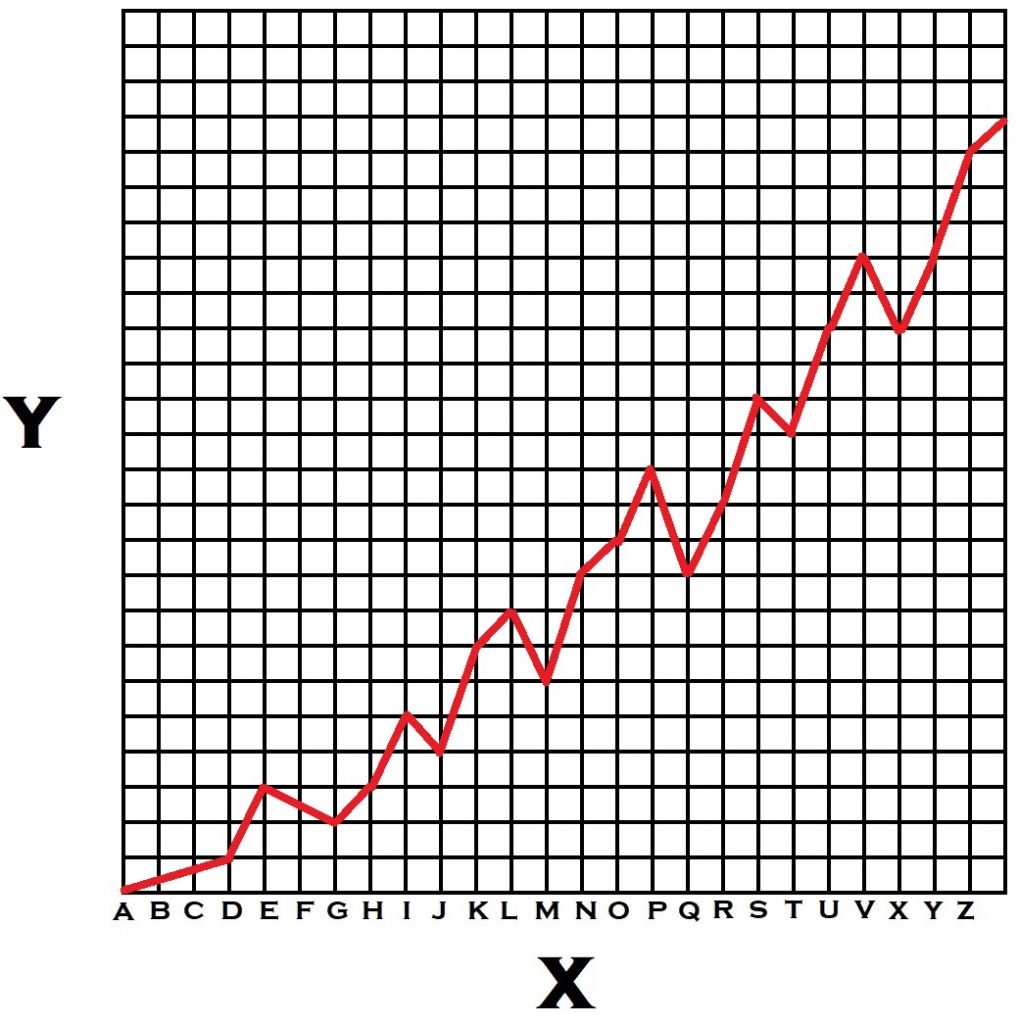

Rather then telling me to shut up or tossing me out of his class, said professor congratulated me for bringing up a good point. What’s considered “great literature” changes all the time. Every time someone publishes a new paper on Brown or Shelly or Lovecraft or Dickinson… the canon changes. A lot of what people refer to as “the classics” now were looked at very differently then. A bunch of them were critical and/or financial failures. A number of them were… well, nowadays some folks would probably call them mass-market tentpole crap. Things written to appeal to the proles. They might’ve made money, yeah, but they weren’t literature.

They definitely weren’t ART.

Now, weirdly enough, at pretty much the same time I questioned my professor about Brown’s book, Robin Williams gave an AP interview and talked a little bit about a theater show he’d done with Steve Martin. “I dread the word ‘art,’” Williams said. “That’s what we used to do every night before we’d go on with Waiting for Godot. We’d go, ‘No art! Art dies tonight!’ We’d try to give it a life, instead of making Godot so serious.”

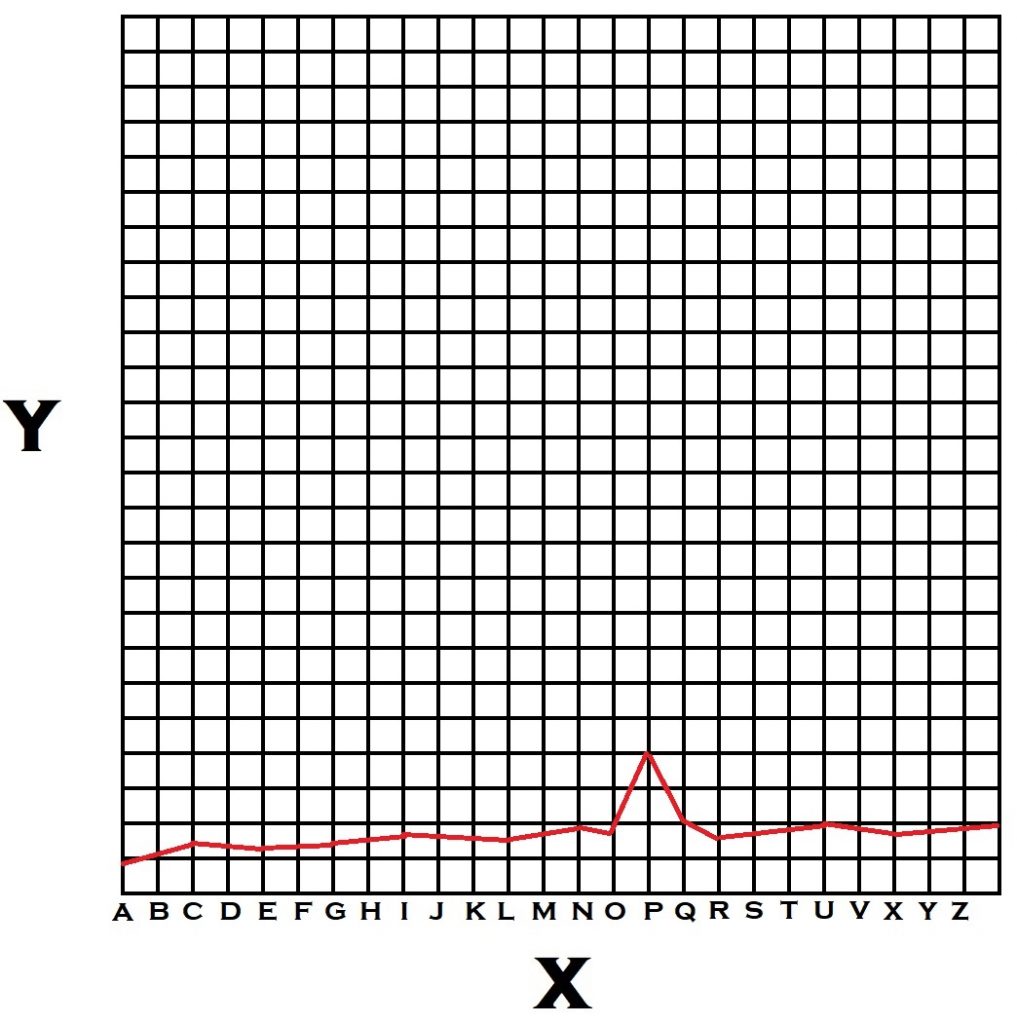

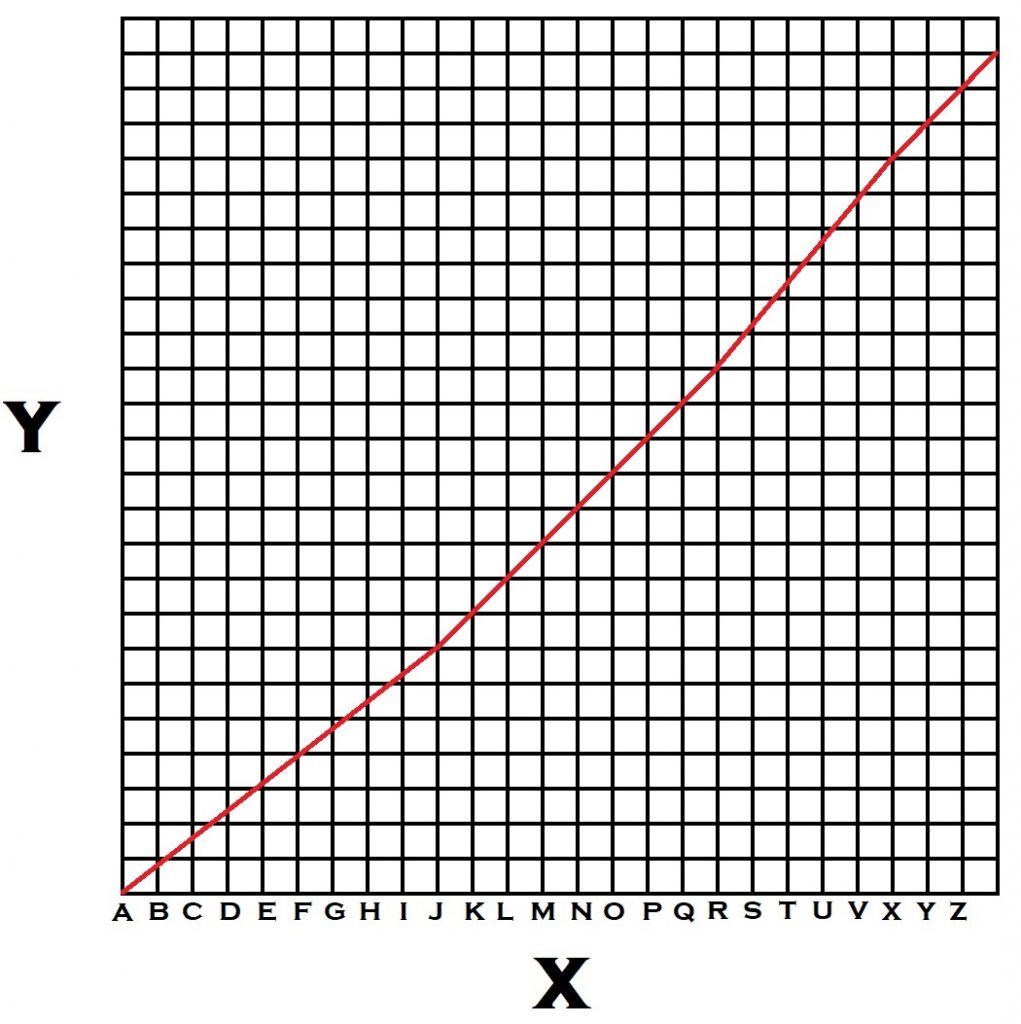

Williams understood something a lot of folks can’t wrap their heads around. We can’t make art. No matter how much I try or how long I work or how many guidelines I follow, art isn’t up to me. It’s up to everyone else. And how they define art changes all the time. With every new paper or critique or review, what was art suddenly becomes shallow and tired. And the fun, entertaining stuff that stands the test of time? Well, now that’s art. Or maybe not. Seriously, there’s no way to tell.

Y’see, Timmy, art in and of itself doesn’t suck. But I really, truly believe that trying to make art sucks. And usually (not always, but very, very often in my experience), the results of trying to make art suck. I think one of the big reasons why is that if I’m trying to make ART it means I’m trying to make my work fit a bunch of preconceived notions about what art should be. Maybe not even my own notions. Could be someone else’s.

So I end up less concerned with, y’know, creating something and more concerned with following rules and delivering messages. And it feels forced and pretentious. It’s so busy trying to be ART that it doesn’t feel alive.

In the early drafts of GJD, I tried to make art. I tried to convey my message. And I made sure that message got in there. Beat it in there. Hammered it into every little gap so people could see how clever I was. So they could see my beautiful ART.

And—looking back on it, being honest—the early drafts kinda sucked. Weird to think that all the beating didn’t make something great. One character specifically—arguably my protagonist in this ensemble piece—really suffered for it. He was just… well, a jerk. He was obnoxious. Irrationally, unbelievably stubborn. Completely unlikable. To the point that my agent cautiously suggested I might want to do a substantial rewrite.

Which I did. And the book was much, much better for it.

Look, here’s the ugly, simple truth. If I don’t have a good story, ART is irrelevant. Really. Because nobody’s going to know about my ART if nobody reads my story. Nobody walks into a bookstore and says “hey, do you have anything with really powerful symbolism?” If my characters are boring or annoying, it doesn’t matter that I’ve got the most magnificent sentence structure and vocabulary ever committed to paper. Because boring stories and boring characters are… well, they’re boring. And when readers get bored they stop reading. That sounds painfully obvious, I know, but you’d be surprised how many people ignore that in the name of ART.

Last time I ranted about this I mentioned a quote (really a quoted quote) from Star Trek: First Contact. “Don’t try to be a great man—just be a man. Let history make its own judgments.” The same goes for my story. It just has to be a good story. One people want to read. Someone else will decide if it’s art or not.

I just need to focus on writing the best story I can.

Next time, I’d like to talk about reading something for the second time.

Until then, go write.