Revisiting an older post with a Halloween themed post! Sort of! But still with lots of thoughts and (hopefully) informative tips and hints.

I’m going to go out on a limb and guess most of you are familiar with The Twilight Zone. It’s one of those lightning in a bottle things that people have tried to re-create again and again over the years. I think we’re up to… three remake series? And the movie?

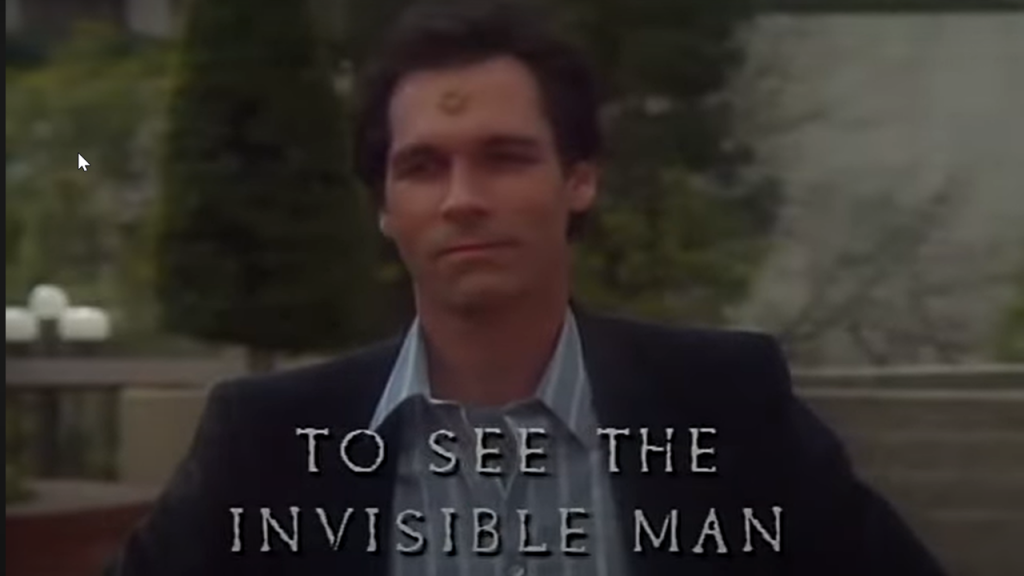

During the ‘80s revival, they did a story called “To See The Invisible Man” (adapted by Stephen Barnes from an old Robert Silverberg short story). It’s about a man in a somewhat-utopian society whose asshole behavior gets him sentenced to a year of “public invisibility.” Key thing though…

They don’t actually turn him invisible. He just gets a small sort of implant-mark on his forehead that tells everyone to ignore him. That’s the curse of it. Everyone can see and hear him–and he knows they can– but no one’s allowed to react to him or anything he does. Even when he desperately needs to be acknowledged (I remember an eerie scene in a hospital emergency room after he’s been hit by a car), people just all pretend he’s not there. Even though they know he is.

Why do I bring this up?

In a weird way, this story’s kind of a metaphor for being a writer. The reader absolutely knows I’m there, that I’ve created this story, made up these characters, and chosen these individual words. But at the same time… they don’t want to admit that. They want to get caught up in the flow and immerse themselves in the story and pretend for an hour or an afternoon or a commute home that all of this is real. That it’s just them and the characters and the plot and I’m… not there. Not part of it.

It’s just my opinion, but I think one of the worst things a writer can do is draw attention to themselves in their writing. We need to be invisible. I mean, we want our characters to be seen. We want our dialogue to be heard. We want our action and passion and suspense to leave people breathless. But us—the writers? We’re just distractions. Less of us is more of the story. Being able to restrain myself is usually just as impressive as how excessive i could be.

So here are some ways not to be seen.

Vocabulary— A fair amount of would-be writers are determined to prove they’re cleverer than everyone else. More often than not, they latch onto (or look up) obscure and flowery words because they don’t want to use something “common” in their literary masterpiece. These folks write sprawling, impenetrable prose and all too often they’ll try to defend this habit by saying it’s the reader’s fault for having such a limited vocabulary. After all, I can easily picture a glabrous man in habiliments of titian and atramentous, not my fault you’re so basic.

Any word I’m choosing just to draw attention, to prove I don’t need to use a common word, is the wrong word. Any word that makes my reader stop reading and start analyzing is the wrong word. I can try to justify my word choice any way I like, but when my reader can’t figure out what’s being said for the fourth or fifth time and decides to put the book down and go get caught up on Haunted Hotel… well, there’s only one person to blame. And it’s not them.

Complication— This is kind of like the vocabulary issue. Sometimes folks try to prove how clever or artistic they are by creating overly-elaborate sentences or structuring their whole narrative in a needlessly complicated way. I mean, I once tried to read a book with—no joke—a three-page opening sentence. Yes, sentence.

If I have an actual reason for doing this sort of thing in this piece of writing, fantastic. But if not… why would I do something that makes my readers more and more aware they’re reading a book rather than letting them get immersed in it? My writing should be clean, simple, and natural.

Said— I just talked about this recently so I won’t spend a lot of time on it here, but said is invisible. People skim over said on the page. It’s fantastic that I know a hundred other dialogue tags, but save them for when they matter. If every single tag is the special one, then none of them are special. So I shouldn’t draw attention to myself with twenty different descriptors on the page when I could just use said.

Names. If I use them in moderation, names are invisible. They’re just shorthand for the mental image of a character. But any name that repeats too often becomes the name we see everywhere and then it becomes noise distracting my readers from, y’know, the things I’m actually trying to show them. When Dot talks to Bob and Bob talks to Dot and Dot calls Bob by name and Bob calls Dot by name and then Bob and Dot… I mean, personally I start flinching a bit at that point.

Y’see, Timmy, every time I make the reader hesitate or pause for a second, I’m breaking the flow of the story. I’m encouraging them to skim at best, put the manuscript down at worst. I never want my reader thinking about how much they’re enjoying the latest Peter Clines book—I don’t even want them to think about the fact that they’re reading. I just want them to be immersed in this world alongside Noah, Parker, Olivia, Sam, Josh, the Castaway, Ross, Dieter, Neith, and all the rest.

If I’m the one they’re looking at, something’s gone wrong.

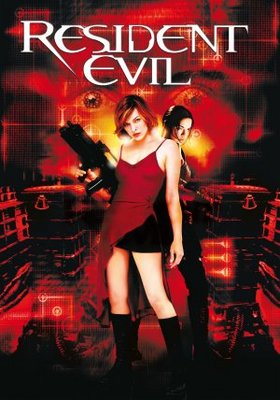

Next time… I thought I’d stick with the Halloweenish theme and do something I’ve threatened you all with for a long time now. I’m going to talk about Resident Evil. A lot.

Oh! And this coming Tuesday night I’m going to be at Mysterious Galaxy in San Diego talking with Eric Heisserer about his fantastic new crime procedural-reincarnation book Simultaneous. You should stop by and check it out.

(and do your homework– go watch Resident Evil)

Until then, go write.