Category: genre

January 14, 2021

So. Much. Winning!

This is one of those posts some folks may feel the need to argue with. It’s a writing tip that’s going to feel obvious to some of you, and ridiculous to others, but I truly think a writer needs to follow if they want any measure of success. And when I say “success” I refer to the classic definition—“making money off your material.”

If I want that kind of success, my hero has to win.

Fair warning, there’s going to be a couple spoilers coming up. Kind of necessary if we’re going to talk about how things end for a character in a story. They’re for pretty big things I’m sure most everyone already knows the ending of, but there’s the warning just in case. If you’re way behind in your required reading or viewing, you may want to stop here.

Also, I’m using hero in the gender-blind sense. If it makes you feel better, feel free to swap in heroine or protagonist. I’m not against any of these terms or the characters they attach to, I’m just using hero because it’s short, and quick and I’m trying to stay focused on this instead of everything going on in the world. So for this post, I’m just talking about the hero.

And the hero wins.

Pretty much always.

Now, there’s a belief in some circles that having the hero of the story fail and die somehow improves the story. That it’s more dramatic. It’s the belief that having something depressing and random happen to my hero is more “honest” because life is often depressing and random. I think this ties back to the frequently-waved buzzwords realism and art. Art imitates life, so if I’m imitating life, I must be making art. That’s just logic. Right?

As I’ve mentioned once or thrice before, this kind of ending sucks. It sucks because we all inherently know the hero is supposed to win, since we identify with the hero. If the hero loses, it means we lost. We’re losers, identifying with another loser.

Believe it or not, this sort of statement doesn’t go over well with most people. I mean (as we’re currently seeing in the real world) people have a lot of trouble dealing with it when a character they’ve invested so much of themselves in doesn’t win.

Now, before people start scribbling down below (for any reason, although I’m sure at least one person already has), let me finish.

I’m not saying every book has to end with happy smiles and people rolling around on piles of money in their new twelve-bedroom mansion. My hero doesn’t need to defeat the cyborg werewolves, save the world, and fly off into the sunset with nymphomaniac heiress Margot Robbie in her private jet.

I’m not saying every book has to end with happy smiles and people rolling around on piles of money in their new twelve-bedroom mansion. My hero doesn’t need to defeat the cyborg werewolves, save the world, and fly off into the sunset with nymphomaniac heiress Margot Robbie in her private jet.

Truth is, the hero doesn’t necessarily need to enjoy winning. I just said they need to win. They may be damaged physically, emotionally, or both. In fact, if my hero ends up wounded or broken after all they’ve done, it just makes us identify with them a little more, doesn’t it?

When they win like this, we often call it a pyrrhic victory. Maybe our hero solves the murder mystery, but loses their best friends in the process. She got revenge, but her lover’s still dead and now she’s a wanted criminal herself. He won the contest, but now his family’s humiliated and wants nothing to do with him. The team tried to save all the hostages but only half of them got out alive. As I mentioned above, victory isn’t an all-or-nothing thing, and my hero can still have a pile of losses even though they’ve succeeded in their main goals. A partial win is still a win.

Hell, the hero doesn’t even need to survive the story in order to win. There are plenty of characters in books and film who didn’t live to enjoy their victories. At the end of Rogue One (here’s that spoiler alert) our two surviving heroes are literally incinerated in the blast from the Death Star’s test firing. And note I say surviving heroes. The rest of their team has already suffered a series of brutal and violent ends. Nobody gets out of that movie. Same with Tony Stark in Avengers: Endgame, cooked from the inside with a single snap of his fingers.

Hell, the hero doesn’t even need to survive the story in order to win. There are plenty of characters in books and film who didn’t live to enjoy their victories. At the end of Rogue One (here’s that spoiler alert) our two surviving heroes are literally incinerated in the blast from the Death Star’s test firing. And note I say surviving heroes. The rest of their team has already suffered a series of brutal and violent ends. Nobody gets out of that movie. Same with Tony Stark in Avengers: Endgame, cooked from the inside with a single snap of his fingers.

And yet, in both of these examples, the heroes win. No question about it. Anyone who’s seen these stories will tell you the good guys won and the bad guys lost.

A key thing here is my character’s motive. What are they trying to do? Keep in mind, their stated goals and their actual goals might not always be the same. Phoebe may say she wants to date the head cheerleader, but what she’s really looking for is romantic love and companionship. Wakko may say he wants revenge, but what he really wants is justice. So they may fail at that obvious, stated goal (dating the cheerleader) or even a broader, more universal goal (keeping their left leg attached), but still succeed with their actual, motivating goal.

Now, I want to mention one other thing, because my friend Stephen Blackmoore brought it up when I mentioned this theory of winning at the Writers Coffeehouse once. There are some stories (a lot in the noir genre, for example) where the hero doesn’t win. In fact, in some cases they fail completely, on all levels, and end up much worse off than they began. This can absolutely happen in stories. Great stories, some of which get a lot of praise and awards.

But…

I think if we named some stories where the hero fails in this complete way, we’d probably realize… they’re not all that well-known. And they’re probably read even less. Again, not saying they’re bad, but it is a much smaller niche of potential readers who’ll enjoy a story where the hero, well, doesn’t really accomplish anything. Even if it’s beautifully written. So there’s nothing wrong if those are the stories I want to write, but I should have my eyes open about how wide an appeal they’re going to have.

Y’see, Timmy… we encounter enough failure and losing in real life that most folks aren’t going to also enjoy it as entertainment. We want to see victories and success and heroic sacrifice because these are the things we dream of in our own lives, and we relate to those people because they’re the kind of people we wish we could be. Even if just for a little while.

Y’see, Timmy… we encounter enough failure and losing in real life that most folks aren’t going to also enjoy it as entertainment. We want to see victories and success and heroic sacrifice because these are the things we dream of in our own lives, and we relate to those people because they’re the kind of people we wish we could be. Even if just for a little while.

So if I’m my plot ends with a massive failure or my hero dies for no reason… maybe it’s worth rethinking that.

Especially if I want to win.

Next time, I’d like to talk about Flashdance.

Until then, go write.

September 3, 2020 / 2 Comments

Comedy Hour!

I know I said I was going to talk a bit about endings but I had this kind of funny epiphany at the grocery store the other day. As in, an actual epiphany about funny things. No, really…

I’ve wanted to talk about comedy for a while. I tried once years ago, but—to be really honest—I didn’t quite have the vocabulary for it at the time. I’m not sure I do now, but at least I thought up two things that sounds kind of clever. That’s better than nothing.

Once or thrice I’ve brought up my bad movie habits and explained them. A fairly common thing I’ve seen are movies that bill themselves as comedies or something-comedies. I say “as” because they’re rarely funny, and I think there’s two big reasons for that. Well, three, but the third one’s not really relevant here. Maybe some other time. For now, two big reasons.

One is that comedy is very empathy-dependent. Possibly more than any other type of writing. If I can’t put myself in other people’s shoes, I’m going to have a tough time figuring out how to make them laugh.

The second reason is what I wanted to blather on about.

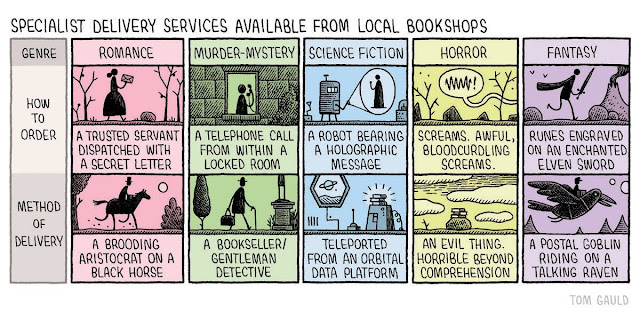

I’ve talked about genres and subgenres here a few times. Sometimes these subgenres have really specific rules. Take horror for example. Cosmic horror stories are not the same as slashers, which are not the same as supernatural thrillers, which are nothing like torture porn, which definitely aren’t monster stories. Or mysteries! There’s over a dozen sub-genres for mysteries, and publishers take them very seriously. Cozies, noir, capers, amateur sleuth, professional sleuth, procedurals… every one of them has their own expectations and requirements and guidelines. I can’t write a cozy mystery about a serial killer who collects his victims’ genitalia. They just don’t work that way.

Comedy is the same way. There are satires, spoofs, farces, romcoms, dramedys, and many more. And just like above, each of these has certain rules and expectations. I can’t just throw down a pile of funny things and declare it to be a spoof. And truth be told, no matter how big that pile of funny things is, I might not even be able to call it a comedy.

Y’see, Timmy, funny is to comedy the same way notes are to music (that’s clever thing #1). You need one to make the other, but that doesn’t mean a pile of one equals the other. I don’t expect thirty random notes to come together and make a song—we all understand I need to arrange them in a certain way, they need to work together, they need to have a certain flow to them. Just like a pile of random ideas doesn’t make a plot, just because I’ve got a pile of funny beats doesn’t mean I’ve got a comedy. What’s funny at the bar might not be as funny at work. That little bit of physical comedy from your date is definitelynot going to go over the same way at work. Heck, it might not have even been that funny on the date.

If you don’t want to believe me, I had a chance to talk with Kevin Smith years ago and we discussed ad-libs. He pointed out something you hadn’t planned or scripted can be incredibly funny on set, but the important thing is that it works in the editing room. Just because it’s funny doesn’t automatically mean it’ll make sense in the final film. ”It’s not germane to the discussion,” was how he put it.

When I’m writing a comedy story or screenplay, I need to be aware of what kind of story I’m telling. Am I adding things because they work within the framework I’ve established and they propel the narrative forward… or am I putting it in because people laugh at poop jokes? Is this part of the comedy, or is it just some random funny element? One that’s hopefully still funny in this context. Hopefully.

More doesn’t always mean better. Just because I add more funny things doesn’t mean I’ve made a better comedy, in the same way that just because I added more types of robots doesn’t mean I wrote a better sci-fi story. And really… does anyone think a bunch of jump scares make for a better horror movie?

Remember, whatever it is I’m writing, my elements should serve my story, not my genre.

(and that’s clever thing #2).

Hey, speaking of whatever it is I’m writing, he said by means of a segue, the exclusive period on my novel Terminus has ended. That means you can pick up the ebook version of the book right now. It’s not narrated by Ray Porter, yeah, but I did include a nice-sized afterword where I talked about where some parts of the book came from and how a lot of the characters developed. And if you’ve been waiting all this time for it, I made it fairly cheap, too, as a small “thank you” for your patience.

Next time… endings. Definitely.

Until then, go write.