A while back I saw Joss Whedon’s fun and super-low budget Much Ado About Nothing. Some of the actors were there and did a little Q & A afterwards. Someone asked Alexis Deinsof about the wisdom of deciding to do a slightly-updated Shakespeare play as a movie. He smiled and said “You can’t start at ‘success’ and work backward to ‘What should I write about?’

A while back I saw Joss Whedon’s fun and super-low budget Much Ado About Nothing. Some of the actors were there and did a little Q & A afterwards. Someone asked Alexis Deinsof about the wisdom of deciding to do a slightly-updated Shakespeare play as a movie. He smiled and said “You can’t start at ‘success’ and work backward to ‘What should I write about?’Category: tips

July 10, 2014 / 3 Comments

Reverse Engineering

A while back I saw Joss Whedon’s fun and super-low budget Much Ado About Nothing. Some of the actors were there and did a little Q & A afterwards. Someone asked Alexis Deinsof about the wisdom of deciding to do a slightly-updated Shakespeare play as a movie. He smiled and said “You can’t start at ‘success’ and work backward to ‘What should I write about?’

A while back I saw Joss Whedon’s fun and super-low budget Much Ado About Nothing. Some of the actors were there and did a little Q & A afterwards. Someone asked Alexis Deinsof about the wisdom of deciding to do a slightly-updated Shakespeare play as a movie. He smiled and said “You can’t start at ‘success’ and work backward to ‘What should I write about?’January 3, 2014

Wherein I Ramble on About What I Ramble on About…

Actually, that’s an even better analogy. Breaking rules is like demolishing buildings. It looks simple, but the folks who do it actually need to know more than the people who built it. They need to understand which walls are load bearing and which beams are supporting, but they also need to know how the material’s going to break or crumble or shatter and how much explosive is needed for each result without there being so much that the building collapses out rather than in.

November 22, 2013 / 3 Comments

The Four Step Program

October 12, 2013

But What About…

Yeah, this is a day late. Lots going on this week, so I thought I could make an exception…

Which, by coincidence, is what I wanted to blabber on about this week.

If you hang out with enough writers (or musicians, or filmmakers, or other artists), either online or in the real world, you’ve probably heard a story about someone who broke the rules and got away with it. And Wakko didn’t just break the rules, mind you… he shattered them. Every one of them. They had to write new rules for him to break. All those people who tell you do this, don’t do that—he ignored them all. And that’s how he got where he is today, with his fame and fortune and living the life we all dream about

People like these tend to get sort of a mythology around them in their respective circles. Which is kind of sad, because these folks—unintentionally or not—tend to make things a lot harder for the folks coming after them. Once I buy into the idea of being the exception, my chances of success drop drastically.

Let me give you an example…

Most of you have probably heard of Cormac McCarthy. He’s a brilliant writer who’s done some wonderful books like The Road and Blood Meridian, among others. He’s also famous for using almost no punctuation, sometimes to the point that his books become difficult to read. Seriously, you’d think the guy got beat up by a pair of quotation marks every day after school when he was a kid.

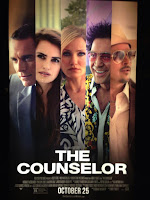

Now, McCarthy decided a while ago that he wanted to write a screenplay. But, being Cormac McCarthy, he didn’t bother to learn how to write one. He just started throwing dialogue and settings down on the page in whatever format looked right to him. And several accounts say the script was…well, a complete mess. Naturally, though, when word got out that he’d written a script, Hollywood went nuts. The script was grabbed, Ridley Scott directed, and it’s coming out in just a few weeks ( The Counselor).

Now, McCarthy decided a while ago that he wanted to write a screenplay. But, being Cormac McCarthy, he didn’t bother to learn how to write one. He just started throwing dialogue and settings down on the page in whatever format looked right to him. And several accounts say the script was…well, a complete mess. Naturally, though, when word got out that he’d written a script, Hollywood went nuts. The script was grabbed, Ridley Scott directed, and it’s coming out in just a few weeks ( The Counselor).

Now, a lot of would-be screenwriters who believe in ignoring the rules saw this as validation. How can anyone say formatting matters after a format-free script sells and becomes a major motion picture? It’s undeniable proof that sort of thing just isn’t important.

Except, well… not exactly.

Cormac McCarthy’s been a legend for twenty years, and was still famous for twenty before that. He could’ve turned in a script written on a used paper plate and the bidding would’ve started at fifty thousand. His status as a novelist made him the exception to the rules of screenwriting. Just because he can do it doesn’t mean I can. Or you can. Or she can.

Here’s the thing…

Exceptions to the rule tend to be rare. Exceptionally rare, you could say. That’s why they’re the exception and not the rule. McCarthy’s script was snatched up by Hollywood despite its poor formatting, but dozens of them are tossed aside every single day for that very reason. Because that’s the rule. Formatting does matter.

And it’s not just screenwriting. For every person who sold the first draft of the first novel they wrote to the first publisher they showed it to, there are millions of people who did not. Yes, E.L. James, Diablo Cody, J.L. Bourne, and a triple-handful of other writers started out by giving their work away for free and then spun that into successful, paying careers as writers. And that sounds fantastic until you stop to consider there are over two billion people on the internet these days. Even if only one percent of them are trying to make money by writing on a blog or website, that puts the odds of success somewhere in the neighborhood of 20,000 to 1 (about 0.0005 % if my math is right). And that’s with a very generous estimate of how many successful writers have followed this path.

I can’t use an exception to the rule as a basis for how things should be done. By it’s very nature, the exception is the freak chance, the aberrant behavior—it’s just not the way things work. Think of the stories you’ve heard about people who survive falling out of airplanes or getting shot in the head. They’re amazing and true and took almost no effort, yes, but they shouldn’t make anyone rethink using parachutes or gun safety.

If I want to succeed, the best thing I can do—whether I’m jumping out of a plane, getting shot at, or writing a story—is to follow the established rules. The absolute worst thing I can do is scoff at those rules—rules like spelling, grammar, or wearing body armor—and decide they don’t apply to me. No matter how amazing my writing is, I need to follow the basic guidelines for my craft.

The reason I should follow them, before you ask, is because the person reading my work is expecting me to follow them. The publishers, editors, and producers who see it before my chosen audience definitely will, and those readers or viewers will assume I’m going to, too. They all have certain expectations they’ve built up, and these expectations all tend to fall in line with the rules.

Now, does that mean amazing, rule-bending things won’t happen or can’t be done? Not at all. My writing may be so spectacular that no one notices the abundant typos. The basic idea could be so clever that nobody will pick up on the fact that all of my characters have about as much depth as a puddle on the kitchen floor. Heck, the structure of my story could be so rock-hard the reader will forgive and forget those incredibly boring opening chapters.

But you know what? Let’s say on page one of my manuscript I introduce school newspaper reporter Tomm Truth and Joanie Justice, and show them straggling with staph editor Barry O’Bama who doesn’t want them running a article about the poor campus seckurity. After a paragraph or two of that my editor’s going to groan out loud. I know when I was a script reader seeing stuff like that made me roll my eyes and add more rum to my glass.

Y’see, Timmy, the minute I see a bunch of clichés, misused words, poor grammar, and misspellings, I’ve rendered a judgment on that writer. Possibly two or three, depending on how many things I see that look wrong. And they may not be wrong for this story—each one may be carefully chosen to set up certain things for later on. But on page one or two or three, they look wrong, and that’s how they’ll be interpreted and that’s going to color my view of the manuscript from here on.

If I assume I’m the exception, that I don’t need to follow certain rules, I’m setting an obstacle between me and the people who are going to pay me to keep writing. Maybe even multiple obstacles. They’re not insurmountable and they don’t guarantee failure. But it does mean I’ve just limited my potential audience. Some readers will toss a manuscript in that big pile on the left after seeing two or three things that look like mistakes. Others will read ten or fifteen pages before setting it aside. And if I can’t prove I am the exception before that happens, I’m going to get a lot of rejections. My story may be loaded with promise, but if my initial foundation looks weak and poorly designed, why would anyone risk the time to see if the rest of it’s structurally sound?

So try to be the exception. Just don’t automatically assume you are. You need to earn it.

Next time… I want to talk about Guido.

Until then, go write.