My sincerest apologies for being late with the ranty blog. Again. It’s not that I don’t care about the baker’s dozen of you who read this collection of nonsense. It’s just that I care more about keeping a roof over my head. It’s nothing personal. Plus, I had a very old friend visit from the east coast, and I care more about her, too.

So, anyway… if you know the second part of that title (many thanks to Paula Abdul), you’re already way ahead of the pack…

I left off in mid-rant having talked about linear structure. Your characters and your action need to have a logical order to them–even if they’re not presented to your audience in that order. Which brings us to the second thing I wanted to talk about, and that’s dramatic structure. While linear structure is experienced within your story (but still perceived by the reader) dramatic structure is experienced by the reader (yet your characters are still aware of many of its elements).

All stories need some level of drama. Drama comes from conflict, and that comes from challenges the characters have to face. They can be action challenges, emotional, intellectual, almost anything. Having to blow up the Death Star before it destroys the Rebel base is dramatic. So is having to face the love of your life who abandoned you in Paris. And so is having to deduce why someone would hire a red-headed man just to copy the encyclopedia.

Now, one challenge all by itself is not a story. If all I have to do is beat the monster and I win, that’s not much of a story, is it? It’s just a step. Readers and audiences don’t want to see someone do X and win. That’s boring, no matter if we’re talking about action, emotion, or pure cleverness. They want to see the hero do A, B,C, X, Y, Z, and win by the skin of his or her teeth. So a good story has a series of challenges for the hero to face, and this is where dramatic structure comes in.

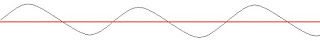

For this next bit, it’d help if you pictured a wave diagram. Just one of those nice up and down ones, perhaps with the zero-level line drawn across the horizon.

(this graphic, by the way, sent today’s ranty blog almost two hundred thousand dollars over budget. Just saying…)

A good story is like a series of waves, each one representing different challenges your characters encounter. The troughs are setbacks they suffer between, or perhaps because of, each success. For example, Indy finds the Ark of the Covenant, but then he gets sealed alive in the Well of Souls with a few thousand Egyptian asps. If your characters never suffer any setbacks (and you’d be amazed how many stories and scripts I’ve seen with this problem) you don’t have waves, you have a line. Likewise, if your story is nothing but an ongoing string of defeats and failures (which tends to go with “artistic” writing), that’s just another line, too. And let’s face it, lines are flat and boring. It’s the same thing as having nothing but “cool” dialogue. It’s just monotonous.

Which brings us to the second part of good dramatic structure. As the story progresses, the waves should be getting taller, every one a little more than the last. The troughs between them should get deeper and deeper. The height of the waves is a good measure of the tension level the characters are facing. The troughs is the level of failure or setback they’re encountering. If you have a kayak or a surfboard, the journey’s pretty smooth near the shore as you’re starting out. You can coast over those little waves without even noticing them. As you get further out, though, closer to where you want to be, the waves get bigger and there can be some serious drops between them. Then you’re at the point where staying down too long means that next wave will just crush you…

To go back to our very expensive graph, there’s a reason for this ever-increasing structure. If the story’s waves are always five up and five down, they cancel each other out and we’re back at that very dull, monotonous line. The all winning/ all losing lines are boring, yes, but you really don’t want that line to be at zero. Each victory should lift the hero (and the reader) a little higher, just as each setback should send them reeling a little harder.

Let’s take a minute to look at Raiders of the Lost Ark. Once we get past that wonderful opening sequence and into the main story, the first few challenges are almost imperceptible. Indy tries to keep his students’ attention, worries about why government agents want to talk to him, and is excited to hear they’ve enlisted him to search for the Ark. He saves Marion from the Nazis only to have her die in an exploding truck. He learns the secret of the medallion and the location of the Ark, but Sallah’s grabbed before he can escape the Map Room. He finds the Ark, but the Nazi leave him buried alive in the Well of Souls. There’s always a “but” in there, all the way up to Indy infiltrating the secret Nazi island and getting Belloq in the sights of an RPG, but Belloq calls his bluff and Indy is finally captured by the Nazis. After all these increasing ups and downs, the big, terrifying up the film ends on is God himself coming down to stomp the bad guys.

Try to beat that.

Now, a few things to watch for as you consider waves, the expensive graph, and your own story.

One is you shouldn’t have two waves which are the same height. If this challenge is equal to that challenge, one of them either doesn’t need to be there or needs to be lessened/increased a bit. Again, when things are the same, it’s monotonous.

Two is these should be valid challenges and they really should be bigger. Don’t fabricate a wave just so your character has a challenge and then try to convince the readers its a vital, integral part of the story. A ninja attack is cool. A ninja who attacks out of the blue just to create an action sequence is not. You don’t want to be the literary equivalent of the surfer who insists the waves in Lake Michigan are just as big as the ones at Venice Beach.

Three is something I touched on above. Dramatic structure is separate from linear structure, because it’s more what the audience is experiencing. Your story can be structured like this…

Ghijkl abcdef mnopqrs wxyz tuv

…but the dramatic challenges still need to go from smallest to biggest. The waves always have to increase with the narrative, not with the actual order of the story. In this example, abcdef should be a bigger wave than ghijkl, even though abcdef happened to the characters first. If it doesn’t increase drama to have it at this point in the narrative, why is it here? This is one of the biggest problems non-linear stories have–there’s no dramatic reason for them to be out of order. I saw one film that was a non-linear mish-mash, but it accomplished nothing except to confuse the audience.

This is leading into something else, and I’ve prattled on a bit too long as it is. So why don’t I stop again and next week I’ll try to finish up with a convoluted definition of narrative. And maybe some more pictures.

Until then, go write.