Okay, so…

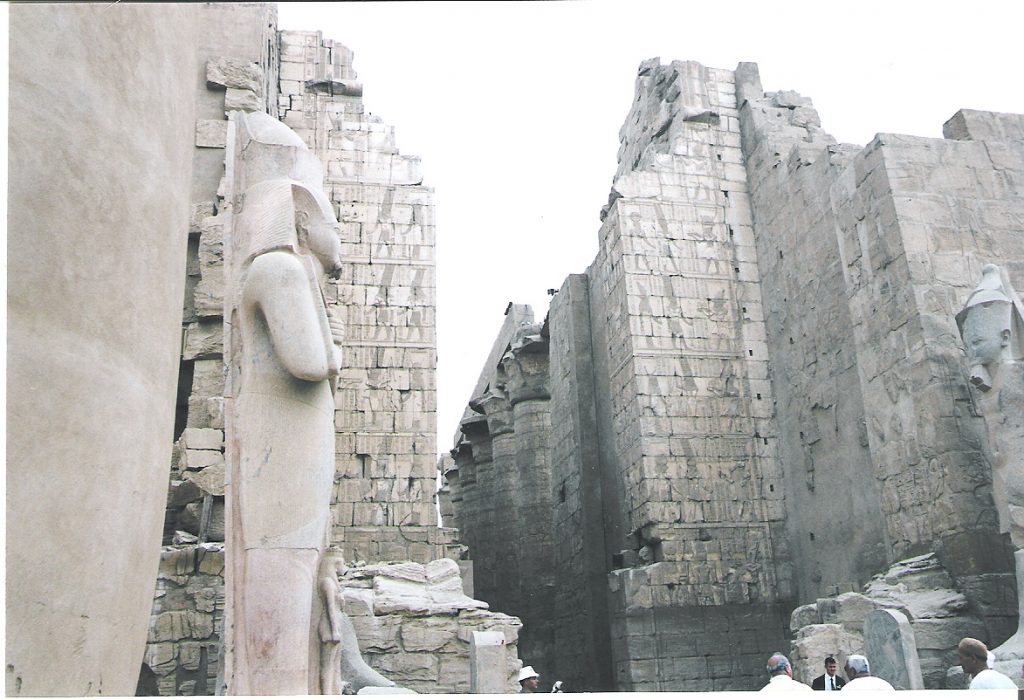

I’ve been fascinated with ancient Egypt since I was very little. Not sure what sparked it, but by the time I was ten I could rattle off the names of a dozen Egyptian gods and their relationship to one another. My fifth grade science fair project was a model pyramid with numerous “reconstructed” tools and a chart of heiroglyphs.

Many years back I was dating a woman and maybe a month into our relationship she mentioned she was going to Egypt in a few months. Would I want to come along? Spend a few weeks traveling Egypt with her?

I tried not to seem too desperate when I said yes.

As someone who grew up in New England, I was used to the idea of having history around you. Not just grandpa’s history or old family history, but serious history. Lots of buildings and landmarks in my hometown in Maine date back to the early 1700s, and the town’s history goes back even further.

But wow… getting to Egypt? There is HISTORY there. Thousands of years of it. I wasn’t ready for the crushing awe of it. And the scale of it. It’s one thing to read about how big some of these monuments are, to see them on television, but you honestly can’t grasp the size of them until you’re right there. Or in some cases, until you realize what you’re seeing in the distance.

I was very lucky that we had no set schedule, so we could go somewhere and just… spend the day. We traveled from Cairo down to Aswan. Stopped for several days in Luxor. I’d just stare at temple walls, statues, and sometimes tombs. One time I just sat for an hour or so on a small cliff above the Valley of Kings and watched boats on the Nile.

Anyway, another thing I saw a lot of in Egypt was folks who spent a lot of time… well, today we’d probably say “taking selfies.” They’d pose in front of this or that, stand with this guide or that guard or hey, look, a camel! And then they’d race off to find the next thing to take a picture with.

It took me a while to realize these folks weren’t really interested in seeing Egypt. They were more interested in telling people they’d been to Egypt. They wanted to show off the photos and tell stories. For them, it was more about the secondary aspects of taking the trip. The after-effects, if you were.

So, while I’m sure this is incredibly fascinating to some of you, I’m sure far more are wondering what all this has to do with writing?

When we talk about writing, I think one thing that gets skimmed over a lot is what our actual goals are. What do we want out of this? Our endgame, so to speak. And this is important because if I don’t know what my real objective is—or I’m not being honest with myself about it—it’s going to be tough to find the right path to reach it.

Like, I’m willing to bet at least one of you reading this has thought “the goal is to get published.” Okay, cool. But what does that actually mean? Do I just want to be able to say someone paid me for a story and it saw print? That’s cool. I think for some folks there’s a degree of validation that comes with getting published, and maybe that’s all they need.

Maybe I just want to tell stories. That’s all that matters. Getting these ideas and situations and conversations out of my head and down on paper (down on electromagnetic bubble? Down on flash drive?) and sharing it with the world somehow. Or not sharing it. Maybe I just write because it’s what I do and it’s therapeutic on some level. Maybe I write a ton of stuff that nobody will ever see, and I’m totally cool with that. Nothing wrong with that.

Or am I hoping to maybe make money? Nothing wrong with that, either. More than a few folks write as a sort of side job. They’ve got their full-time career and writing’s what they do on weekends or the occasional late night, selling a short story or novella or even a full book. Or maybe the goal is to make writing itself the full-time career. To make enough money stringing words together that I can pay my bills, live in semi-comfort, and don’t need to do anything else.

But maybe the money’s irrelevant, and so’s publication. What I really want is for people to recognize that I’m good at this. Very good. Masterclass good. Maybe I want the accolades and the starred reviews and the numerous awards where I get to stand in front of people who understand how talented I am.

Or look, maybe I just want to be a writer because I want to be part of the club. That group gathered at the bar at the con. Those people online making clever comments to each other. I want to be in with them, and maybe I want people to look at me the way they look at those folks. It might sound a little silly but there are clearly people who only want to be writers for this… the same way those folks only wanted to say they’d been in Egypt. The want the destination, not the journey.

(yes, this may be me talking about a current hot topic)

Y’see, Timmy, there’s a ton of different reasons I may want to write. And whichever one is my reason… that’s fantastic. But I think it’s important to be aware of why I’m doing this. Because there are a lot of paths open to writers these days, and I don’t want to spend time and energy on a path that’s taking me away from what I really want.

So be honest. With other folks and yourself. What do you want?

Next time…

Actually, before I talk about next time, I wanted to bounce something off you. How many of you use the “categories” there on the side (also sometimes called tag or labels or…)? I was thinking of paring the list down a bit to make it easier to use. None of the tags will actually go away, they just won’t be in that list anymore. I was thinking I’d snip out all the proper names—nice easy way to lose twenty or thirty lines, and it’ s probably one of the least-used ways to search for things, yes?

Anyway…next time I’d like to talk a little bit about the devil. Specifically, the one in the details.

Until then, go write.