A random thought…

Well, not that random.

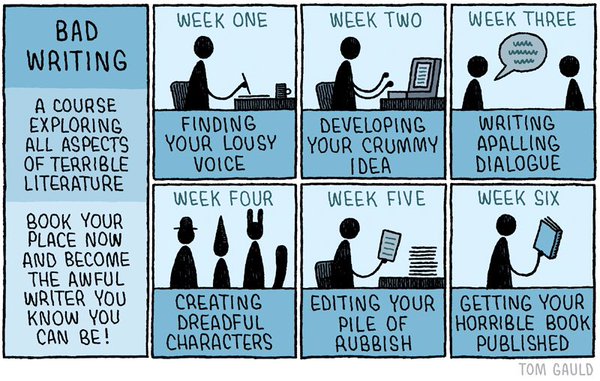

The other day I made a smart-ass response to a friend’s Twitter comment about different online writing aids and apps. There’s a bunch of them out there these days. Some of them highly publicized. My comment was… snarkily negative. Let’s leave it at that.

I know. Snarkiness with friends. What has the internet come to? It’s all downhill from here.

Anyway, it did get me thinking about these different sites a bit. I mean, a good writer wants to use all the tools available, right? Is this just me inching ever-closer to cranky old manhood?

I don’t think so.

Okay, first off, let’s not even talk about the information side of this. If someone wants to hand over a bunch of their intellectual property to a random website and feels completely confident they’ve read and understood every single line of the terms of service… that’s up to them. We’ll leave that discussion for others.

I want to blather on about how useful these sites are, both short-term and long-term.

So… let’s talk machines.

(I feel hundreds of fingers poised over keyboards, ready to lunge at the comments section…)

The most common computer tool we’re going to encounter is a spellchecker. Pretty much every word processor has one. Lots of websites do, too. Blog sites like this one, Twitter, Facebook—they’ve all got some basic spellcheck capacity.

That’s the important bit. Basic. The absolute best spellcheckers are, if I had to put a number to it, correct maybe 97-98% of the time. Don’t quote figures at me—I’m saying right up front that’s just based off my own experience. These are the spellcheckers we usually find in the word processors. The online ones… I’d drop it down into the 88-90% range. Maybe even a tiny bit lower.

What does this mean? Well, there are words that have accepted alternate spellings, but a spellchecker will say they’re wrong. There are also lots of common words—especially for genre writers—that won’t be included. I was surprised to discover cyborg wasn’t included in my spellchecker’s vocabulary. Or Cthulhu. Okay, not quite as surprised on that one, but still…

Keep in mind, spelling is a basic, quantfiable aspect of writing. We can say, no question, whether or not I’ve spelled quantifiable correctly in that last sentence (I didn’t). That’s a hard fact (and, credit where credit is due, the spellchecker kept insisting we needed to change it).

Also—a spellchecker doesn’t know what word I meant to use. It can only tell me about the word on the page. Or the closest correctly-spelled word to that word on the page. Maybe it’s the one I wanted, maybe not. At this point it’s up to me to know if that’s the right word or not. And if I don’t know… well, things aren’t looking good for my manuscript.

Consider all the things I just said. The gaps. The problems. The rate of accuracy. And this is with the easiest aspect of writing. Spelling is a yes or no thing. It’s right or it isn’t. This is something a computer should excel at… and the online ones are getting a B+ at best.

How accurate do you think an online grammar program is?

Grammar’s a lot more complex than spelling. Spelling’s just a basic yes or no, but grammar has a ton of conditionals. Plus, in fiction, we bend and break the rules of grammar a lot. I tend to use a lot of sentence fragments because I like the punch they give. A friend of mine uses long, complex sentences that can border on being run-ons. I know a few people who remove or add commas to help the dramatic flow of a sentence.

And hell… dialogue? Dialogue’s a mess when it comes to grammar. A big, organic mess. Fragments, mismatched tenses, mismatched numbers, so many dangly bits… And it needs to be. That’s how we talk. Like I’ve mentioned in the past, dialogue that uses perfect grammar sounds flat and unnatural.

Think about this. I’ve talked before about Watson, the massive supercomputer that was specifically designed by MIT to understand human speech… and still had a pretty iffy success rate. Around 72% if my math is right. And it might not be–I’m not a mathematician, after all.

Think about this. I’ve talked before about Watson, the massive supercomputer that was specifically designed by MIT to understand human speech… and still had a pretty iffy success rate. Around 72% if my math is right. And it might not be–I’m not a mathematician, after all.

D’you think the people who made that grammar website put in the time and work that was put into Watson?

So, again… how accurate is that online grammar program going to be?

More to the point, how useful is it going to be as a tool? Would you pay for a DVR that only records 3/4 of the shows you tell it to? Do you want a phone that drops one out of every four calls?

Now, I’d never say there’s no use for these tools or sites. But it’s very important to understand they’re not going to do the job for me. They’re the idiot writing partner who’d really good at one thing, so I kinda need to keep both eyes on them when they’re set loose to do… well, that thing. I need to know how to spell words and what they mean. I still need to know the rules of grammar—even moreso if I plan on breaking them.

See, that’s the long-term problem. Assuming this professional writing thing is my long-term goal, at some point I need to learn spelling and grammar. If I’m going to keep depending on someone (or something) else to do the work for me… when am I going to learn how to do the work?

Y’see, Timmy, these programs and apps are kinda like alcohol. They won’t make up for a lack of knowledge. They’ll just emphasize it. I definitely don’t want to be dependent on them. At best, if I know what I’m doing and I’m careful (and use them in moderation), they might make things a little more smooth and painless.

Next, a quick screenwriting tip.

Until then, go write.

You go write. Not your computer.

Go on… go write.