For those who came in late…

So we’re in the middle of a big discussion/lecture/infodump about story structure. To be more exact, the different typesof story structure, because there are several of them and they all serve a different purpose. If you missed me blabbing about linear structure last week, you might want to jump back and read that first. Or maybe re-read it as sort of a refresher before we dive into this week’s little rant.

Speaking of which…

Now I want to talk about narrative structure. Remember how I said linear structure is how the characters experience the story? The narrative structure is how the author decides to tell the story. It’s the manner and style and order I choose for how things will unfold. A flashback is part of the narrative structure, as are flashforwards, prologues, epilogues, and “our story begins ten years ago…” If you studied (or over-studied) this sort of stuff in college, your professor may have tossed out the term syuzhet.

One more note before I dive in. Within my story there might be a device or point of view, like a first person narrator, which gives the appearance of “telling” the story. For the purposes of this little rant, though, if I talk about the narration I’m talking about me, the writer, and the choices I make. Because I’m God when it comes to this story, and the narrator doesn’t do or say anything I don’t want them to.

That being said… here we go.

In a good number of stories, the linear structure and narrative structure are identical. Things start with Wakko on Monday, follows him to Tuesday, and conclude on Wednesday. Simple, straightforward, and very common. My book, The Fold, fits in this category. It’s loaded with twists and reveals, but the linear structure parallels the narrative. Same with Autumn Christian’s We Are Wormwood, Dan Abnett’s The Warmaster, or Maggie Shen King’s An Excess Male. These books may shift point of view or format, but they still follow a pretty straightforward linear narrative.

We don’t need to talk about this type of narrative too much because… well, we already did. When my narrative matches my linear structure, any possible narrative issues will also be linear ones. And we discussed those last week.

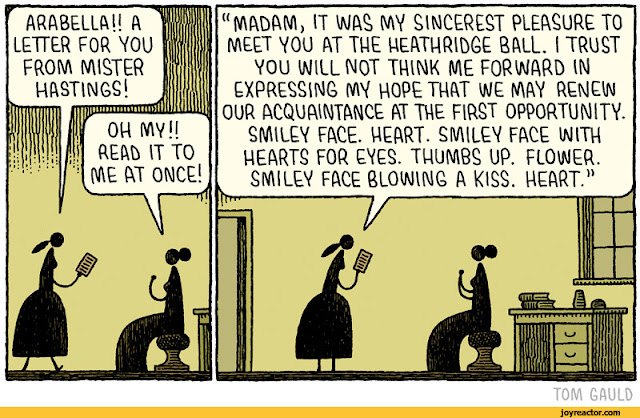

There are just as many stories, though, where the narrative doesn’t follow the timeline of the story. Sometimes the writer does this with flashbacks, where a story is mostly linear with a few small divergences. In other instances, the story might split between multiple timeframes. Or the story may be broken up into numerous sections and the reader needs to follow clues as to how they all line up. These are often called non-linear stories, or you may have heard it as non-linear storytelling (it was the hip new thing for a while there). My own Ex-Heroesseries employs numerous flashbacks, all in their own linear order. So does F. Paul Wilson’s latest, The God Gene. In his “Vicious Circuit” novels, Robert Brockway splits almost every other chapter between present day and the events of forty-odd years ago.

Narrative structure involves more than just switching around my story elements, though. It’s not just something I can do off the cuff in an attempt to look trendy. If I’ve chosen to jump around a bit (or a lot) in my narrative, there’s a few things I have to keep in mind.

Be warned, we’re moving into an area that requires a little more skill and practice.

First off, putting things in a new narrative order can’t change the linear logic of my story. As I mentioned above, the week goes Monday through Friday, and this is true even if the first thing I tell you about is what happened on Thursday. Monday was still three days earlier, and the characters and events in my story have to acknowledge that. I can’t start my book with everyone on Thursday baffled who stole the painting, then roll the story back to Monday where everyone was a witnesses and saw the thief’s face. If they knew then, they have to know now. If I have Yakko act surprised to find a dog in his house on Friday and then have the narrative jump to him adopting the dog from a shelter on Tuesday, I’m going to look like an idiot while my linear structure collapses.

These are kinda stupid, overly-simple examples, yeah, but you’d be surprised how often I’ve seen this problem crop up. Writers want to switch stuff around in clever ways, but ignore the fact that the logic of their story collapses when the narrative elements are put in linear order. This is an easy problem to avoid, it just requires a little time and work.

The second thing to keep in mind when experimenting with narrative structure is… why? Why am I breaking up my story instead of telling it in order? Sure, all that non-linear stuff is edgy and bold, but… what’s the point of it in mystory? Why am I starting ten years ago instead of today? Why do I have that flashback at that point? How is the narrative improved by shaping it this way?

Now, these may sound like silly questions, and I’m sure many artsy folks would sweep them aside with a dry laugh. But they really deserve some serious thought. I talked a little while ago about how when my reader knows things can greatly affect the type of story I want to tell. By rearranging the linear order, I’m changing when people learn things.

And if this new narrative form doesn’t change when people learn things… again, what’s the point?

The third and final issue with having different narrative and linear structures is that people need to be able to follow my plot. I mentioned last time that we all try to put things in linear order because it’s natural for us. It’s pretty much an automatic function of our brains. This flashback took place before that one. That’s a flash forward. This flashback’s showing us something we saw earlier, but from a different point of view.

The catch here is that I chop my narrative up too much, people are going to spend less time reading my story and more time… well, deciphering it. My readers will hit the seventh flashback and they’ll try to figure out how it relates to the last six. And as they have to put more and more effort into reorganizing the story (instead of getting immersed in said story), it’s going to break the flow. If I keep piling on flashbacks and flash-forwards, and parallel stories… that flow’s going to stay broken. Shattered even.

The catch here is that I chop my narrative up too much, people are going to spend less time reading my story and more time… well, deciphering it. My readers will hit the seventh flashback and they’ll try to figure out how it relates to the last six. And as they have to put more and more effort into reorganizing the story (instead of getting immersed in said story), it’s going to break the flow. If I keep piling on flashbacks and flash-forwards, and parallel stories… that flow’s going to stay broken. Shattered even. And when I break the flow, that’s when people set my book aside to go watch YouTube videos. No, it doesn’t matter how many clever phrases or perfect words I have. People can’t get invested in my story if they can’t figure out what my story is. And if they can’t get invested… that’s it.

Y’see, Timmy, narrative structure can be overdone if I’m not careful. This is something that can be really hard to spot and fix, because it’s going to depend a lot on my ability to put myself in the reader’s shoes. Since I know the whole linear story from the moment I sit down, the narrative is always going to make a lot more sense to me, but for someone just picking it up… this might be a bit of a pile. Maybe even a steaming one.

That’s narrative structure. However I decide to tell my story, it still needs to have a linear structure. Perhaps even more important, it still needs to be understandable.

Next time, I’ll try to explain how linear structure and narrative structure combine to (hopefully) form a powerful dramatic structure.

Until then… go write.