Despite the title, you might like this little rant…

We talked about characters for a while at the Writers Coffeehouse this past Sunday. Mostly about my long-standing (but sometimes contentious)

three necessary character traits. And I figured I’d already threatened all of you with a character post, so we could spin off in a slightly different direction here…

I can’t have a story without characters, right? Should be obvious. Oh, sure, I’ve seen one or two clever pieces that are just elaborate settings with no actual people in them, but I’m going to say

999,999 times out of a million no characters means no plot, no story, no nothing. They don’t need to be human. They don’t even need to be alive. But if my reader doesn’t have someone to focus, I’m going nowhere fast.

For all of us, the goal’s to create characters that seem alive on the page. People a reader can identify with and picture in their mind. Characters will make or break my writing, which means they deserve attention.

A mistake I see again and again and again, however, is writers who give their characters

too much attention. Their writing becomes all about character and not about

anything else. These characters never get off the page because… well, they get buried alive there.

A couple of good rules-of-thumb. As always,

your mileage may vary, but these seem to be pretty solid and common, in my experience.

I shouldn’t describe characters in exacting physical detail. I’ve mentioned this before. We, the audience, don’t need to know someone’s precise height, weight, waist, inseam, shoe size, cup size, hair color, eye color, or how much of what they shave and how often. We really don’t need to be told the exact tie pattern he’s wearing, where her skirt hits her thigh, if he likes boxers or briefs, if she likes thongs over bikinis, how many fillings either of them have, the name of her first pet, the state his parents grew up in, how they both did on that third grade geography test, and precisely what they had at the restaurant last night for dinner–including condiments.

I don’t need any of that in my writing. I promise. Because these sort of long descriptions bring things to a grinding halt. The longer the description, the louder the squeal of brakes. And the harder the crash.

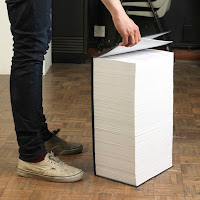

When I do this, I’m doing an infodump. I’m throwing out

a pile of information at a time the reader wants action and forward motion (which is—for the record—always). It’s wonderful to know that, as Phoebe steps out into the street, everyone notices her D & G bag, Yves St.Laurent jacket, eel-skin boots, platinum wedding band with matching engagement ring (not to mention the size of that rock—three carats, easy), the small St.Christopher’s medallion she wears outside her emerald-green satin blouse, her meticulous eyeliner, and her $300 hairdo that’s starting to sag, giving her one loose strand that hangs loose over her face in a kind of sexy way as she puffs and swipes at it with her free hand.

You know what’s far, far more interesting than all of that, though? Why’s Phoebe stepping into the street? Is it a crosswalk? Is she getting into a limo? Throwing herself in front of a bus? She’s been frozen there in mid-movement while the writer (in this case, me) prattles on about her clothes and hair. Heck, after all that description, did you even remember she was outside?

There’s another simple reason to not spend time on

physical descriptions, whether I’m writing a novel or a screenplay. Silly as it sounds… I don’t have much say in what this character looks like. When we read, we all form our own mental images, and they’re usually pretty different from the ones written out. An example I’ve mentioned before, from Dan Abnett’s excellent

Ravenor books, is the character of Kara Swole, who I always picture like my friend Penny from college. Their descriptions don’t really match up (well, they’re both female gymnasts, but that’s about it) yet this is how I picture Kara as I read each chapter. Something just clicked in my mind and that’s what she looks like.

But

my Kara probably doesn’t look like

your Kara. If you read the books, maybe you picture her more like Melissa Benoist. Or Zazie Beetz. Or that cashier at the grocery store you were kinda crushing on.

So extensive, super-elaborate physical descriptions are probably going to be a waste of everyone’s time. I should use broad strokes and only fill in details where I really need to. Pick three or four good descriptive words for the character (not their clothes), and stick with them. Their dialogue and actions will bring them to life and my readers will fill in the rest.

In the novel I’m finishing up right now, one of the main characters is a tall, dark skinned woman with frizzy hair who wears the same uniform/jumpsuit as everyone else. You’ve got her in mind just off that, don’t you? Without anything else. Yeah, a hundred people are going to interpret that description a hundred different ways, but

you’ve got a solid image in your head, yes? Which means I’m now free to go talk about her new Caretaker job on the Moon and how it goes

horribly wrong when that meteor hits out at Hades Cemetery and the dead start to rise and hey this is already more interesting than a long list of personal details, isn’t it?

Now, as far as the

mental/ emotional/ historical side of my character goes, if this stuff is important, of course it should be included. If my romantic lead has lost everyone he’s ever cared about, if my adventurous heroine suffered from asthma as a child, or if a knowledge of rural New England history will be critical to resolving this mystery, then there’s a chance these things need to be in my writing.

However, there’s a good rule of thumb for all of this stuff, too (so many thumbs).

Is it critical to what’s going on

within these pages? My audience is going to assume

if I’m giving all this information, it’s because they

need this information. After my fourth or fifth exhaustive description of a given character’s childhood traumas, college love life, or medical history, my reader’s going to make the natural assumption none of this is going anywhere and start skimming. First they’ll skim paragraphs, then pages, and then over the bookshelf or television listings to see what else could be filling this time…

Now, there’s an argument to be made that any event in someone’s past affects their present and every single decision shapes a person’s life to some degree. As a wise man once said, we are the sum of our memories. Thus, anything I choose to include is relevant to the story on some level, right?

Well… sort of. A point I’ve tried to hammer home many, many times before—

this is not real life. No one wants to read about a character’s personal or family history that doesn’t have any bearing on what they’re experiencing right now.

Again, for example…

When I was five years old I saw my dog, Flip, get hit by a car in Maine. That same year I got stabbed in the eye with a pair of sewing scissors. I got my heart horribly broken junior year of college, to the point that several friends thought I might kill myself. A year after graduating from UMass, I decided to move to California on a whim, quit my job on the spot, and spent two weeks quietly terrified that I’d made the worst decision of my life.

All formative event that still affects me to this day? Absolutely.

Do they have anything to do with the tips, rules, and suggestions I post here?

Not really.

But they build character, right? They all expand the vast tapestry of my life. They tell everyone here a little bit about me and make me more human.

So what?

I’ve got an actual story, don’t I? I don’t want to waste your time with stuff that has no bearing on the writing advice you’re here for. If I want to focus on one thread in the tapestry of my life, I should choose one that shows them how my life relates to this.

I’ll tell you about how annoyed barely-a-teenager me was when a doctor casually told me that writing wasn’t “a real job.” I can explain how thrilled high school-senior-me was when I got a personal letter from Tom DeFalco rejecting my Marvel Comics story but including some tips, a Marvel submission guide, and a full copy of one of his

Thor scripts for reference. I can give you the wonderful visual of me in a panicky, cold sweat sitting outside Ron Moore’s office, waiting to pitch a few

Deep Space Nine stories I’d come up with. And maybe I can break

the rule of threeand finish it off with the story of

financially-desperate megetting an offer to write

some bonus material for Audible just when I

reallyneeded the money.

See? That’s all relevant. You’re reading that and saying “Wow, this guy’s been serious about writing for a while now, hasn’t he?”

That’s the kind of stuff I need to put in my writing. The relevant

description and backstory. The stuff that matters to the story I’m telling.

And you’ve forgotten my dog’s name, haven’t you? No, don’t worry about it. He’ll always be important to me, but I understand why he’s not important to you. Especially in this context.

No, really, I do.

Build fantastic characters. But don’t build unnecessary stuff. Or, at least, don’t put it in your story.

Next time… well, I’m on a deadline so you may just get something quick from me. or maybe a guest post. We’ll see.

Until then… go write.

In the novel I’m finishing up right now, one of the main characters is a tall, dark skinned woman with frizzy hair who wears the same uniform/jumpsuit as everyone else. You’ve got her in mind just off that, don’t you? Without anything else. Yeah, a hundred people are going to interpret that description a hundred different ways, but you’ve got a solid image in your head, yes? Which means I’m now free to go talk about her new Caretaker job on the Moon and how it goes horribly wrong when that meteor hits out at Hades Cemetery and the dead start to rise and hey this is already more interesting than a long list of personal details, isn’t it?

In the novel I’m finishing up right now, one of the main characters is a tall, dark skinned woman with frizzy hair who wears the same uniform/jumpsuit as everyone else. You’ve got her in mind just off that, don’t you? Without anything else. Yeah, a hundred people are going to interpret that description a hundred different ways, but you’ve got a solid image in your head, yes? Which means I’m now free to go talk about her new Caretaker job on the Moon and how it goes horribly wrong when that meteor hits out at Hades Cemetery and the dead start to rise and hey this is already more interesting than a long list of personal details, isn’t it? I’ll tell you about how annoyed barely-a-teenager me was when a doctor casually told me that writing wasn’t “a real job.” I can explain how thrilled high school-senior-me was when I got a personal letter from Tom DeFalco rejecting my Marvel Comics story but including some tips, a Marvel submission guide, and a full copy of one of his Thor scripts for reference. I can give you the wonderful visual of me in a panicky, cold sweat sitting outside Ron Moore’s office, waiting to pitch a few Deep Space Nine stories I’d come up with. And maybe I can break the rule of threeand finish it off with the story of financially-desperate megetting an offer to write some bonus material for Audible just when I reallyneeded the money.

I’ll tell you about how annoyed barely-a-teenager me was when a doctor casually told me that writing wasn’t “a real job.” I can explain how thrilled high school-senior-me was when I got a personal letter from Tom DeFalco rejecting my Marvel Comics story but including some tips, a Marvel submission guide, and a full copy of one of his Thor scripts for reference. I can give you the wonderful visual of me in a panicky, cold sweat sitting outside Ron Moore’s office, waiting to pitch a few Deep Space Nine stories I’d come up with. And maybe I can break the rule of threeand finish it off with the story of financially-desperate megetting an offer to write some bonus material for Audible just when I reallyneeded the money.