Decade-old pop culture reference, but it’s still relevant. And fun. Especially today.

As a lot of the book covers over on the right suggest, I’m big on superheroes. Have been for years and years now. They’re a popular topic these days, too. Comics. Television. Movies. I tend to get asked about them a lot, and I talk about them a lot.

Because superheroes are so popular, people are slapping that label on lots and lots of stories. There’s a distinction that needs to be made, though, and I think it’s one some folks have trouble grasping. And since so much of being a good writer is grasping those little details, I thought it would be worth going over. Apologies, because this one’s going to be a little more lecture-ish.

First… a little history.

The whole idea of masked avengers arguably started with The Scarlet Pimpernel. There’s probably a strong case to be made for the Count of Monte Cristo, but I think for this little rant the Pimpernel’s probably the best example. It was a 1904 story by the prolific Emma Orczy about a swashbuckler who fought for the oppressed in Robespierre’s France by using a series of disguises and a circle of secret operatives. There was also Doctor Syn (a.k.a. the Scarecrow of Romney Marsh) in 1915, Zorro in 1919, and then a series of comic book superheroes like The Phantom and The Spider before we started seeing familiar folks like Batman in 1939 (seventy five years ago almost to the day, in fact).

Interesting point, though… None of these characters had any sort of actual powers. They were just mortal men (and a few women, even back then) with a lot of training and skills who hid their true identities behind a mask or elaborate disguise.

Now, on the other hand, stories of people with actual superhuman abilities have been around for thousands of years. Literally, thousands. Gilgamesh, Hercules, and Icarus all had superpowers centuries before the birth of Jesus (who, arguably, also had some powers of his own). The regenerating Green Knight first appeared in medieval Arthurian legends. The Grimms wrote up several stories about the strongest man in the world, the fastest man in the world, the man with the sharpest hearing, and so on. Robert Louis Stevenson created a scientist who could change into a monster, and H.G. Wells had one who could turn invisible. In modern day times, Stephen King started his career with a telekinetic teenager, a precognizant schoolteacher, and a pyrokinetic little girl. Alexander Key, Dean Koontz, and Stephen Gould all wrote novels about people who could teleport.

However… are any of these characters actually superheroes?

My point is, superheroes and superpowers are, and have pretty much always been, two separate things. One doesn’t necessarily require the other. And, like a lot of story forms, if I get confused about which one I’m telling, things can go in a lot of weird ways that… well, don’t work.

Now, some folks claim, for example, that Gilgamesh was always a superhero story. So were all the Greek and Norse myths. That’s what superheroes are, right? Modern mythology?

I kind of disagree with this. H.P. Lovecraft once made the very clever observation that we couldn’t have true

supernatural storiesbefore the 19th century because until then people really didn’t know what the

naturalwas. So trying to re-classify older stories doesn’t work. I think the same thing applies here. There were many tales of heroes with superhuman powers and abilities before the Scarlet Pimpernel, but I’d argue the idea of an actual superhero story didn’t exist until the early 20th century. There was a definite split there into those two distinct forms—super

hero stories and super

power stories.

And, as I mentioned above, if I don’t know which one I’m writing, it can cause some problems. They’re not interchangeable, and some of the concepts don’t play well together.

Let’s go over a couple basics I’ve observed over the years…

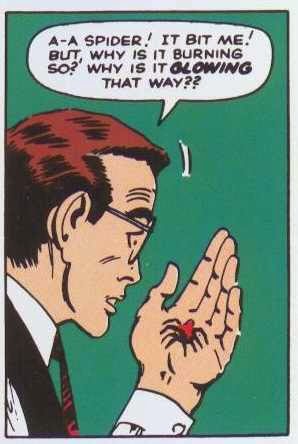

Right at the start, I’ve noticed that superpowers stories tend to brush over the origin of said powers. In both Jumper and the Harry Potter books, we’re just told that this is the way the world has always been. Some folks get the teleport gene. Some can do magic. That’s it. If superpower tales do have an origin in them, they tend to lean toward the hard sciences, making it as believable as possible… but still pretty much brushing over it.

With superheroes, though, the origin is pretty much a standard. A writer can also get away with somewhat sillier, softer-science origin stories. More than a few characters have gotten superpowers from blood transfusions (including one of my own). Lots of folks stumble across magic or alien artifacts. Radiation was a common source of superpowers for decades, despite what we learned in seventh grade science class. Heck, Stan Lee wrote a story where someone got their powers by standing near a nuclear bomb when it went off. Absurd, yes? Yet here we are today and that’s still the accepted origin of the Incredible Hulk (though they’ve quietly retconned him a bit further away from ground zero).

As far as

character motivations go, a super

herostory is almost always defined by a person who makes a conscious decision to publicly use their powers for a wider goal that may not benefit them (and often doesn’t). Most of them feel morally compelled to use their abilities this way. They aren’t doing it to show off or to get even with someone. Obvious as it may sound…superheroes act heroically.

This public nature also means they deal with public sentiment of one kind or another. Iron Man’s a celebrity in just about every sense of the word. Superman’s an iconic part of Metropolis. Captain America’s a venerable historic figure. Batman and Spider-Man receive mixed reviews. The X-Men are openly considered criminals.

In a super

powers story, the characters may have superhuman abilities, but

their motivation tends to be personal, and their actions are usually behind-the-scenes. When powers are revealed in superpowers books, it’s almost never a good thing. Consider

Carrie and

Firestarter, both of which I hinted at up above. In each book the girls hide their powers until they need them (for revenge and to rescue her father, respectively) and when their powers are revealed these are moments of absolute horror. The Green Knight tests the character of knights on a one-at-a-time basis, and if you know that tale you know the awful way people learn about his powers. In

The Dead Zone, Johnny Smith’s trying to save the world, but he has to do it alone and secretly because no one will believe him. Hiding your powers and staying apart from the world is a main theme in both the

Harry Potterand

Percy Jackson books.

The abilities in super

hero stories tend to be much more extreme, too. There’s Superman and the Sentry, two examples of

the “living god” superhero. For decades the Flash could actually run faster than the speed of light. The Scarlet Witch could alter reality on a planetary scale while Phoenix could telekinetically manipulate matter on a molecular level. The only limit to what a Green Lantern ring can do is the wearer’s imagination.

Compare this to super

power stories, where powers are usually much more “believable” and often have limiting side effects. In

The Dead Zone, Johnny Smith hemorrhages when he uses his powers too much, and so does Charlie’s dad in

Firestarter. In Dean Koontz’s

The Bad Place, teleportation can mean scrambling your body, your mind, or both. In

Limitless, the IQ-enhancing drug can (and usually does)

kill you when you go into withdrawal. In fact, the only two superpower stories I can think of where someone has overwhelming powers would be Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel

The Lathe of Heaven and the film

Dark City (but if you can think of others, please let me know).

In a superhero story, I’d say a costume is almost necessary, much in the same way a cowboy needs a hat and a horse. Mostly because it’s how my hero or heroine protects their secret identity and the people around them. However, I will toss out the proviso that putting my main character in a costume doesn’t make my story a superhero story, just like putting them on a horse doesn’t automatically make it a western.

Super

powers stories involve street clothes. Even if someone has a “uniform” way of dressing, it tends to be suits, boots, leather jackets, and other things that wouldn’t look that out of place on a city street. Hercules didn’t have a special outfit for performing the twelve labors. Carrie doesn’t duck out of her prom to put on a leotard and a domino mask. On

Grimm, Nick tends to just dress like a police detective, even when he knows he’s going up against Wesen or other monsters.

I also think a lot of this difference has to do with

the world a given story is set in. More often than not, a super

powers story has a very realistic setting. Aside from a very limited, few beings (most of whom stay out of the public eye), there’s almost nothing to distinguish it from the real, day-to-day world we read about online. And that’s going to affect what characters know and how they react to things. Even how they interact with each other.

By contrast, look at the settings for some of our well-known superheroes. In both the Marvel and DC universes, the existence of aliens—several types of aliens—is a well-documented fact. New York was very visibly invaded by aliens in The Avengers movie. Superman’s a known alien. So are Hawkgirl and Hawkman. Green Lantern works for aliens. Magic is real in both universes, too. Spider-Man is a common sight swinging through his version of New York, where the Avengers and Fantastic Four both have very public office building. Heck, I think the Avengers have two or three buildings at this point.

So, all that being said…

I think one of the problems with pushing a superpowers story into the superheromold is the silliness factor. The motivations don’t always work as well. When someone puts on a costume in a real world setting, it tends to feel like the writer isn’t taking things seriously. In the final chapter of the BBC’s Jekyll, when Dr. Jackman unites with Hyde to become truly superhuman, It would’ve been ridiculous if he’d stopped to pull on a leotard and cape. There’s a well-meaning little indie film called Sidekick where the hero does just that in the third act to rescue his love interest, and it feels completely absurd.

You get similar issues going the other way, too. People historically read superhero comics for escapism. We want to see Superman fly around the country, not walk across it. When someone picks up the latest Incredible Hulk, they want to see him get angry and perform some feats of amazing strength, usually coupled with some amazing property damage. While some of the issues Doctor Banner’s dual personality causes him are interesting, nobody opens an issue of the Hulk really hoping to see ten or eleven pages of Bruce sitting in a diner discussing physical strength vs. spiritual strength with the waitress. I think Marvel and DC’s sales figures over the past few years will back me up on this. The audience for superhero stories isn’t looking for stark realism.

This is also why some things in related universes just don’t mix well. John Constantine is part of the DC Universe, but he doesn’t really fit with in with the Superman, Captain Atom, Green Arrow crowd. Neither does Dream of the Endless. Marvel has zombie hitman Terror, who also is clearly in the Marvel universe but just never sat right alongside Spidey, Captain Marvel, Daredevil, and the rest. Whenever these two types of characters interact it always seems awkward, and one or the other doesn’t really feel right.

Now, granted, these aren’t formal rules that have been set down by tenured professors. If we just look at a lot of fiction, though, we’ll see that this separation of powers (so to speak) has been around for ages. I’ve given a bunch of examples here, and even more when I first talked about this idea a few years ago.

As always, I’m sure someone can dig around and find that one story where Constantine teamed up with Green Lantern and it was magnificent. But overall, if I’m going to play with super-powered characters, it’s probably a good idea to be clear what kind of story I want to tell. Because if I don’t… well, there might be some clashes. Not the fun bare-knuckle kind, either.

Next time, while I try to finish up this new draft before

Texas Frightmare, I’d like to talk about drafts.

But until then, go write.

It’s probably worth mentioning that if I’m making changes that do radically alter my plot or characters, what it really means is that I don’t have a solid draft yet. Yeah, even if I’ve done six drafts before this. If I suddenly realize Yakko should be my main character while Dot’s the supporting character who dies in the second act… that’s a big change. That’s a lot of changes. It means different interactions between different characters, new motivations, possibly a whole new linear structure. And it also means I’m kind of going back to square one. Now I need to tweak and cut and make adjustments to this plot and story.

It’s probably worth mentioning that if I’m making changes that do radically alter my plot or characters, what it really means is that I don’t have a solid draft yet. Yeah, even if I’ve done six drafts before this. If I suddenly realize Yakko should be my main character while Dot’s the supporting character who dies in the second act… that’s a big change. That’s a lot of changes. It means different interactions between different characters, new motivations, possibly a whole new linear structure. And it also means I’m kind of going back to square one. Now I need to tweak and cut and make adjustments to this plot and story. Well, I’d argue not much of my work falls in the same genre, unless we’re talking in broad, sweeping terms. I’ve got a superheroes vs. zombies series (sci-fi fantasy with some soft horror), a suspense-mystery-horror novel, a sci-fi thriller, a classic mash-up where I share credit with Daniel Defoe, and I just started work on a historical time-travel road trip story. I’ve also got some short stories out there that are straight horror, some that are straight sci-fi, and even a pulp action war story.

Well, I’d argue not much of my work falls in the same genre, unless we’re talking in broad, sweeping terms. I’ve got a superheroes vs. zombies series (sci-fi fantasy with some soft horror), a suspense-mystery-horror novel, a sci-fi thriller, a classic mash-up where I share credit with Daniel Defoe, and I just started work on a historical time-travel road trip story. I’ve also got some short stories out there that are straight horror, some that are straight sci-fi, and even a pulp action war story.