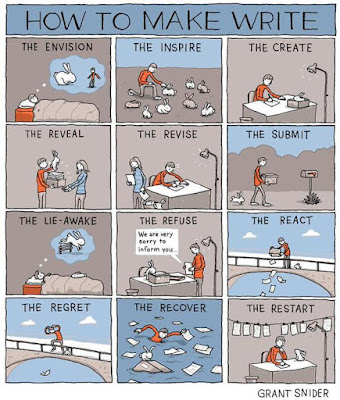

If the title of this week’s rant sounds familiar, you’ve probably read or watched a lot of how-to pieces. Y’know, the ones that say something like “Here’s how to turn this stuff we scavenged from a dumpster into a full wedding reception –with food—in just six simple steps.” Or maybe it’s “Learn how to play concert piano in four easy lessons.”

We’ve probably all tried one of these at least once. Okay, maybe tried the belly fat ones twice. And a few things become clear pretty quick. If I’ve tried a few of these, I’ve probably also noticed a few recurring issues with these steps…

1) They still require lots of practice. Yeah, this is easy to do—on the nineteenth try. The first eighteen are going to be messy and somebody might die, but by my nineteenth attempt I should be getting completely adequate results.

1) They still require lots of practice. Yeah, this is easy to do—on the nineteenth try. The first eighteen are going to be messy and somebody might die, but by my nineteenth attempt I should be getting completely adequate results. 2) They often require lots of other skills or equipment. Learning the ceremony is easy once you’ve got a working knowledge of the Basque language. Yes, making these carrot roses is no problem at all as long as I have a 1 3/4” mellonballer (not a 2”—that’ll ruin the whole thing).

3) They’re rarely simple. A lot of times each of these “easy steps” ends up sounding like that guy at Comic-Con who walks up the microphone and says “I have a five part question, but first I just want to say how wonderful it is that all of you have come out to meet all of us, and the positivity in this room reminds me of a poem by Emily Dickinson, which I’d like to read a few lines from…”

4) They’re rarely effective. In the long run, most of these “four-or-five easy steps to accomplish something” methods just aren’t worth it. Oh, I might learn a small trick or polish a skill, but in the end, all the money and time and frustration wasted on trying to do it the easy way could’ve been spent on learning… well, how to do it. If I really want to learn how to make carrot roses that look fantastic, maybe I should actually… well, learn how and not try to figure out some trick that’ll let me skip the learning curve.

4) They’re rarely effective. In the long run, most of these “four-or-five easy steps to accomplish something” methods just aren’t worth it. Oh, I might learn a small trick or polish a skill, but in the end, all the money and time and frustration wasted on trying to do it the easy way could’ve been spent on learning… well, how to do it. If I really want to learn how to make carrot roses that look fantastic, maybe I should actually… well, learn how and not try to figure out some trick that’ll let me skip the learning curve. Oddly enough, this kind of ties back to something I mentioned a while back. It’s a hypothesis I came up with during my time in the film industry and, well, it’s stood up to all my testing and research so far. Maybe next time I write about it I’ll be able to refer to it as a theory.

I call it the four step rule. Pretty much everyone’s professional career goes through four stages.

*Not knowing what I’m doing.

*Thinking I know what I’m doing.

*Realizing I don’t know what I’m doing.

*Knowing what I’m doing.

I don’t remember exactly how I stumbled onto this, but it was one of those instantly-makes-sense things. I know my film career followed it. And just looking around set, I could see it in all the people I worked with and where they fit into this pattern. In fact, the more I looked, the more I came to realize this pattern applied to almost everything. I could see it with people on movie sets, yeah, but also with the staff members for an online game I worked on for a while. I have a friend who was a police officer, and he agreed a lot of cops followed the same pattern.

Now, there’s an unfortunate side-effect of this. I also noticed a few people who were pretty mediocre workers, but were convinced they were amazing. These folks were stuck at step two because they never had (or never acknowledged) that slap down moment. They never bothered to improve because they never acknowledged a need to improve. They just stayed at those early, flawed levels.

I’m sure most of you can see that all of this applies to writing, too. When I first sat down to write a story in third grade, every aspect of it was a mystery to me. I didn’t even know what I didn’t know. Character elements, linear and narrative structure, dialogue —these terms meant nothing to me. Of course, once the words were typed out in front of me, it was clear I was a genius. I mean, look at them—they’re typed!

Alas, many editors did not agree with my assessment of those pages, and I had a good sized stack of rejections before I had body hair. And that file folder got thicker and thicker for many years.

I think I was in college when I started to consider that every single editor I submitted to might not be the problem. Maybe my stories weren’t genius just because they were typed. Yeah, the ones I was writing at that point had a much more elaborate vocabulary than my old ones (and I used it as often as I could), but were they really any better than the ones I’d been writing at age eleven…?

I had dozens and dozens of rejections under my belt, but it turned out I really didn’t know much about writing or storytelling. All my “experience” was essentially eight or nine years of doing all the wrong things. I’d missed opportunities and ignored good advice because I was convinced I knew it all.

And being able to admit that was what let me finally improve. And improving was what let me get where I am today. Working with other professionals who treat me like a professional. Able to offer actual advice with experience backing it up (even if a chunk of that experience is, “wow, I screwed up a lot back then…”).

Now, last time I talked about these four steps, a few folks asked me if it was possible to skip some of them—specifically, step two. If I realize I’m at step one, can I jump right to step three? I’ve thought about this on and off, and also heard a few things in other interviews and articles that fit into this little outline. So I’m going to say this…

No. You cannot skip any of the steps. If I tell you that I did skip step two, it really means I’m stuck there and in denial.

It comes down to, as my lovely lady has called it, paying your dues. We all have to do it. We can pay our dues sooner and get it over with or pay them later with interest. I can get down in the gritty, sweaty, unrewarding trenches and take the long route—doing all the work and learning how to do it. Or I can rely on nothing but luck, tricks, and gimmicks to get me there in a tenth the time—and then fall from a much greater height when it comes out I don’t know how things are done. I’m sure we can all think of tons of Hollywood stories of someone who shot to the top in record time, only to come crashing all the way back down to where they started out (or even lower…).

It comes down to, as my lovely lady has called it, paying your dues. We all have to do it. We can pay our dues sooner and get it over with or pay them later with interest. I can get down in the gritty, sweaty, unrewarding trenches and take the long route—doing all the work and learning how to do it. Or I can rely on nothing but luck, tricks, and gimmicks to get me there in a tenth the time—and then fall from a much greater height when it comes out I don’t know how things are done. I’m sure we can all think of tons of Hollywood stories of someone who shot to the top in record time, only to come crashing all the way back down to where they started out (or even lower…). Y’see, Timmy, we need that screw-up stage. It’s important. Not to sound all new-agey or melodramatic, but it’s the crucible that burns away the screw-ups and forges us into better writers. We go in like iron, but we come out like steel. If we don’t go through it, we’ll never be as good as we could be.

All that being said… It is possible to manage how much time you spend on step two. How do we do it?

I need to be open to criticism. And to listen to it. Try not to be defensive. Learn how to tell valid feedback from personal preferences. Be able to admit something isn’t good or doesn’t work like it’s supposed to. Yeah, it’ll be frustrating and disheartening and there’s a good chance I’ll find out I spent a lot of time on something that’s just going to go in the circular file. But if I’m open to learning from all that—to admitting I need to improve—that’ll speed up the learning process.

One last thought. Joe Quesada—an artist/writer/editor-in-chief at Marvel Comics—made a wonderful observation in his foreword to Brian Michael Bendis’ storytelling book Words For Pictures. “If you’re not falling, you’re not trying hard enough.” If I don’t screw up now and then, it’s probably a good sign I’m not trying too hard. If I never challenge myself, I’m never going to get better.

We all need to fail. And it’s okay to fail. The only problem is if I’m determined not to learn from it.

Next time, I’d like to talk to you about something you may have seen before. And before. And before.

Until then, go write.