Many thanks for your patience after a very fun but also kind of exhausting SDCC week. I saw some fantastic things, got to talk with some fantastic people, picked up a few great exclusives, and overall had a wonderful time. But yeah… all set to not do anything for a week or so now.

Except some book stuff.

And staying caught up on the ranty blog.

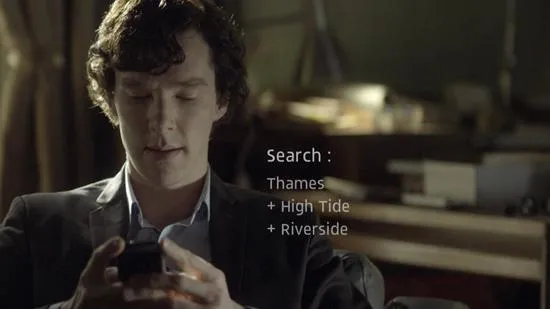

There’s a concept you may have heard of (or some variation of) that we’ll call compressed storytelling. As the name implies, some events are compressed or eliminated so I can focus on others, usually with the goal of keeping my story from getting much larger than it needs to be. Alfred Hitchcock—director, storyteller, partner of the Three Investigators—once said that drama is real life with all the boring parts cut out. That’s also a good way to sum up compressed storytelling.

Most short-form type of storytelling—movies, episodic television, comic books, short stories—are usually compressed to some degree or another. If you think about it, in the vast majority of cases, I can’t turn in a three hour script for an episode of Strange New Worlds or a ninety page script for a comic book. Either of these will get my submission tossed immediately. Ugly truth is, this holds for novels, too. They have an upper limit (for a few reasons) and if my first novel is a thousand pages long it’s probably not going to find a home anywhere.

Also, it sounds kind of obvious, but compressing the story builds pressure. It increases tension for the reader and knocks the stakes up a bit. There’s a big difference between having two months to raise the money to save Uncle Ricky’s Surf Shop and only having two days to do it. Likewise, if I’m telling the story of those two weeks in three hundred pages or six hundred pages… one’s probably not going to feel quite as urgent, even though they’re telling the same story.

Another way to think of it is compressed storytelling is the idea that we can skim over a lot of events and time without it affecting our story. In fact, often things work a lot better without it. I’m actually dealing with this right now—trying to figure out how much I can cut from a draft while keeping the story and the tone intact.

Plus, let’s be honest. As it is, we don’t need to see everything. We all know this. If it’s day one and our heroine’s wearing a red shirt and on day two it’s a blue shirt, we don’t need a chapter where she changes clothes to understand what’s happened. Or even a page. Odds are we don’t need to bring it up at all.

Now, we could call the flipside of this decompressed storytelling. It’s when I take my time and include everything. And I mean everything. Every single fact and detail and random thought, whether they’re relevant to the story or not. If we’re going to believe that Hitchcock quote up above, this is when we add all the boring parts back in. And this is often done in the name of art and drama.

Y’see, Timmy, the problem here is that decompressing the story takes the pressure off my characters. When I pause to describe all the different aliens in the bar, it means the pacing in my story has slowed way down. If my characters have time to sit around discussing Phoebe’s string of failed relationships (again) then it’s hard for me to say all that other stuff going on is that urgent. I can’t tell you it’s life or death important that Wakko and Yakko reach Washington before noon tomorrow, but then have ten pages of them stopping for lunch, chatting with the waitress, considering today’s specials, discussing franchise restaurants vs small town diners, and then describing each exquisite bite of that club sandwich in vivid detail. Also, why are they in the diner? Were they going somewhere to do… something?

And yeah, of course there will be exceptions. Good characters will have a weird conversational segue or two… but not thirty of them. That one person walking by might deserve an extra-long look because they’re so creepy or sexy or suspicious… but not every pedestrian we pass. We want to know what Yakko is doing while he’s waiting for the kidnapper to call, but we probably don’t need to keep track of how many times he absently scratches his butt.

Okay, moment of brutal honesty. In my experience, some writers fall back on this sort of decompressed storytelling because… well, they don’t actually have much story to tell. I can’t make my novel lean and tight, because if I did it’d only be three chapters long. So I fill it up with segues and character moments and drawn out descriptions.

The excuse is that I’m being “literary.” I’m raising the bar and writing at a higher level than the rest of you. All you people who keep skimming over those introspective monologues and exquisite details and beautiful language in favor of things like “plot” and “action”… all of you are the real problem here.

Again, there’s always a place for these things, like I said before. But if my writing is all one or all the other, though—completely stripped down or not stripped down in the slightest—maybe I should pause for a moment and look at this from both directions. Do I actually have a story and a plot? Are my characters dynamic and trying to resolve a conflict? Or am I using decompressed storytelling to hide the lack of these things behind a lot of flowery language and drawn out, irrelevant dialogue?

Are my characters fleshed out? Is my setting well established? Am I skimming past plot points as fast as I can so nobody has time to notice I don’t actually have any…?

If any of this rings a little too true… maybe it’s time to adjust the pressure a bit.

Next time, I’d like to share a few thoughts about getting into (and out of) trouble.

Until then, go write.