This week—requests are granted! Also, as you may have noticed, the majority of responses I got in comments/ tweets/ DMs/ etc were in favor of the new layout, so I’m going to stick with it for now.

A few weeks back someone asked about characters. How do I get a sense of who they are. How do I make sure when they do something it’s what they’d do instead of just what the plot (and by extension—I ) want them to do?

Okay, these are two related-but-different questions. Let’s look at each of them on their own, then figure out that relationship-overlap. Which I think is what we’re aiming for with this request.

Also, because there’s a lot to unpack here, expect a lot of links to previous posts. I don’t want to bury you in too much rehashed stuff. You’re here for exciting hot takes on the art of writing, yes?

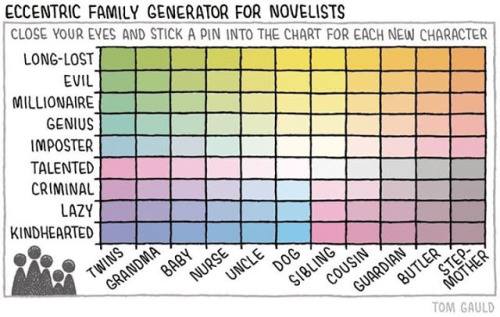

First off, how do I get a sense of who my characters are as individuals? What makes them unique? What makes them stand out?

One thing would be their general backstory and personal preferences. If I’ve got a character—especially one of my main characters or important supporting ones—I should know a lot about them. And I’m talking about me, the author. For almost all of my characters, there are things I know about them that never make it into the books. Maybe it’s about their relationship with their parents, their worst class in school, or their favorite bands. It can be games they play, people they’ve slept with, or their first car. A lot of this sounds like weird stuff, yeah, but all of this says a little something about who someone is, which means it’s going to affect how they react to the world around them.

One thing would be their general backstory and personal preferences. If I’ve got a character—especially one of my main characters or important supporting ones—I should know a lot about them. And I’m talking about me, the author. For almost all of my characters, there are things I know about them that never make it into the books. Maybe it’s about their relationship with their parents, their worst class in school, or their favorite bands. It can be games they play, people they’ve slept with, or their first car. A lot of this sounds like weird stuff, yeah, but all of this says a little something about who someone is, which means it’s going to affect how they react to the world around them.

There’s also their voice. The way people phrase things and the words they choose. Their background will have an effect on how they act, and it’s also going to effect how they talk. This is one of the easiest ways to make characters distinct on the page (or in an audiobook).

Also, I could think about how people react to this character. Do folks wince at the sound of Dot’s voice? Do they instinctively lean away from Wakko? Do they lean toward Phoebe? And are people right to react this way, or is it because they know something else that we don’t?

All of this should give me a really good sense of who my character is. Again—I probably won’t use all of it. I may never see Yakko stumbling through a date or listening to music or reminiscing about his old VW Bug. But these are all the little elements that help move a character from a basic stereotype and into actual, memorable person-hood.

Okay, the second part of all this is about these characters making decisions.

There’s a term you may have heard around the interwebs called agency. It first appeared back in the 1700s, when people were having Enlightening discussions about philosophy and sociology. At its simplest, agency refers to free will. Can a person make their own choices and affect the world around them? How much does the world they exist in restrict that ability to make choices? If I can’t travel alone, vote, or choose who to love… do I have free will, or just the appearance of free will? Do people in prison have free will? Free will may have gotten them there—or maybe the conditions forced on them by society did—but now they have almost no freedom to make choices at all, so…? Is there a point where I no longer have free will?

Anyway, that’s all heavy stuff. It’s a little different (and easier) for us when we’re talking about agency in a literary sense. Fictional entities don’t have free will because they’re… well, they don’t actually exist. But as a writer, I need to make my readers believe these characters are real people who are having an actual affect on the world around them. They need to do things, and these things need to matter. If cowards are suddenly going to leap forward and be brave, there should be a clear reason. If a cold person falls madly in love, we should understand why and how. If someone decides to open the spooky mystery box after it’s killed half their friends… well, we should be with them on this, even if we don’t like it.

Yeah, sure, it’s possible to make inconsistent decisions or choices that move the plot forward. We’ve all seen it happen. The wonderful A. Lee Martinez(he of the Constance Verity books and the Save The Movies podcast) came up with plot zombie a little while ago to explain this. It’s when characters are only acting in service of the plot, not out of any actual developed or established character traits.

Yeah, sure, it’s possible to make inconsistent decisions or choices that move the plot forward. We’ve all seen it happen. The wonderful A. Lee Martinez(he of the Constance Verity books and the Save The Movies podcast) came up with plot zombie a little while ago to explain this. It’s when characters are only acting in service of the plot, not out of any actual developed or established character traits.

This is, just to be clear, a bad thing. Y’see, Timmy, my characters need to face challenges and need to respond to them. They need to make choices—ones that are consistent with who they are. And the results of these choices should have a real affect on how the story plays out. Because if they’re not… Well, then they’re not really doing anything. They’re just empty puppets. Not even the good kind of puppets. They’re just sock puppets that I’m using to try to convince my readers this is a real story.

So make your characters do things. In character.

Next time, I’d like to look at some things from a different angle.

Until then, go write.