Warp core breach! Warp core breach!

Is it just me or does Starfleet build really shoddy warp cores? “Oh my God, Ensign Lefler spilled her coffee! We have an imminent warp core breach…”

Anyway, I’ve blathered on about linear structure and then about narrative structure. Now I want to talk about how they interact and tie together. It isn’t really that complicated an idea, but I’m going to use a few examples to make things extra-clear.

As I mentioned before, narrative structure and linear structure are two very different things. The narrative structure is the story the audience is experiencing while the linear structure is what the characters are experiencing. Today I’d like to talk about how they work together, but to do that I need to talk about a third part, and that’s dramatic structure.

Dramatic structure stands a bit off from the other two. It’s an inherent quality of the story that comes about when the linear and narrative work together correctly. Probably the best way to look at it is that this story needs to be told this way to have the impact the storyteller was going for.

For example…

Spoilers, by the way, but if you don’t know this one by now… c’mon, seriously.

The Sixth Sense is the story of Bruce Willis, the ghost of a child psychologist who’s helping a little boy come to terms with the fact that he can see ghosts.

Hmmmm… Well that’s kind of lame when you tell it like that, isn’t it? Sound like some kind of Hallmark/ Lifetime/ Afterschool Special sort of story. And to be blunt, it is. If The Sixth Sense was structured that way, telling you everything up front, it would be a very different story, even with all the same events and dialogue.

In fact, that’s probably the best way to look at it. Dramatic structure is why spoilers are cool in a story, but kind of lame when your friends blurt them out or you read them on websites (sorry, AICN). It’s why a lot of screenwriters and directors don’t like to talk too much about some story elements ahead of time, and why they get frustrated with publicists who do.

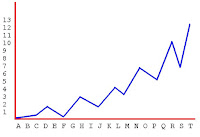

So… that being said, what I’d like to do now is show you a graph. I don’t really believe in graphs and charts and page counts when it comes to storytelling. I do believe they can make a handy visual aide now and then, though.

This one cost IBM seven-point-six million dollars. It’s the real reason they built Watson. The whole Jeopardy thing was just a fortunate side-effect.

On this chart, the horizontal axis is the narrative. It’s the book from page one to page five hundred, or the movie from opening shot to closing credits. The vertical line is, to coin a phrase, tension. It can represent kickass action scenes or romantic conflicts or scariness or just tension built from suspense.

Very, very simply put, this is dramatic structure. Going from the norm to the extreme. Starting at calm and relaxed only to end at DefCon5. Even if it’s just an emotional/ spiritual DefCon5.

A good story is a series of waves or peaks on this chart. Each one represents a different challenge your characters encounter. The high points are triumphs and peaks of action. The low points are setbacks they suffer between, or perhaps because of, each success.

This first chart is an average day in anyone’s life. To be honest, it’s my life. You can pick out me getting woken up out of a dream by my cats. There I am on the treadmill. That’s where I discovered we were out of Diet Pepsi and the Britta filter was empty. For a good chunk of it I’m sitting here at my desk writing. There’s watching Chuck and making dinner with my lovely lady and catching the end of that Castle two-parter with the dirty bomb. As you can see, nothing horrible, but nothing life-changing, either.

This first chart is an average day in anyone’s life. To be honest, it’s my life. You can pick out me getting woken up out of a dream by my cats. There I am on the treadmill. That’s where I discovered we were out of Diet Pepsi and the Britta filter was empty. For a good chunk of it I’m sitting here at my desk writing. There’s watching Chuck and making dinner with my lovely lady and catching the end of that Castle two-parter with the dirty bomb. As you can see, nothing horrible, but nothing life-changing, either.

For the record, everyday life is dull. This may have come up here before. It’s boring because we all see it every day. No matter how perfectly or beautifully or eloquently that everyday life is copied to paper or movie screen, it’s still boring. The chart proves it. Ordinary life is pretty darn close to a straight line.

Now, here’s something else important to keep in mind. If your characters never suffer any setbacks (and you’d be amazed how many stories and scripts I’ve seen with this problem) you don’t have waves, you have another line. Likewise, if your story is nothing but an ongoing string of defeats and failures (which tends to go with “artistic” writing), that’s just another straight line, too. And let’s face it, lines are flat and boring. It’s the same thing as having nothing but “cool” dialogue. It gets monotonous fast.

This brings me to the next part of good dramatic structure. As the story progresses, those waves and peaks should be getting taller, every one a little more than the last. They are, in fact, building on each other, just like a good story should. Likewise, the troughs between them should get deeper and deeper. The height of the waves is a good measure of the tension level the characters are facing. The troughs are the level of failure or setback they’re encountering.

This brings me to the next part of good dramatic structure. As the story progresses, those waves and peaks should be getting taller, every one a little more than the last. They are, in fact, building on each other, just like a good story should. Likewise, the troughs between them should get deeper and deeper. The height of the waves is a good measure of the tension level the characters are facing. The troughs are the level of failure or setback they’re encountering.

Going back to our very expensive graph, there’s a reason dramatic structure works this way. If my story’s waves are always five up and five down, they cancel each other out. The all winning/ all losing lines are boring, yes, but you really don’t want that line to be at zero. Each victory should lift the hero (and the reader) a little higher and a little further, just as each setback should send them reeling a bit harder.

Because of this, you shouldn’t have two peaks which are the same height, especially not right next to each other. If this challenge is equal to that challenge, then the writer hasn’t built anything up in the pages between them. When you see two peaks that carry the same emotional/ action/ suspense/ horror weight, you should stop and think. One of them either doesn’t need to be there or it needs to be lessened/ increased a bit. Again, when things are the same, it’s monotonous.

It’s also worth mentioning that these all need to be valid challenges. A writer can’t fabricate an unmotivated conflict or three just so the character has a challenge. Pirate attacks are cool. Pirates who attack out of nowhere just to create an action sequence are not, no matter how much the writer tries to convince readers the attack is a vital, integral part of the story. This is a common flaw you can spot in a lot of old pulp writing, because the format required multiple cliffhangers, each at a regimented spot in the story. The story would be going along and suddenly the hero or heroine would encounters a wild animal or a booby trap or find him/herself at gunpoint. There was no logic to it, it just had to happen because we’re on page 42.

So, keeping all of this in mind, I’m going to go for the big one… This is the one would-be writers mess up all the time. It’s not going to be easy, but hey… if it was, everyone’d be doing it.

Dramatic structure always wins in the end. No matter what the linear structure of your story is, no matter which narrative structure you’re using, the dramatic structure of a story should always be escalating. You can have setbacks, but all the motion has to be forward and the net gain has to be positive (positive meaning building on itself, not necessarily happy and cheerful). As I’ve said many, many times before, telling the story has to be a writer’s first priority. The narrative structure must match the dramatic structure.

However…

You may have caught up above, the linear structure doesn’t have to follow this pattern of escalation. In fact, it’s very powerful when it doesn’t. Well, when it doesn’t and you’re doing everything else right… Linear structure can start huge and then decline for the rest of the story. It can have a high point in the middle or the biggest low right in the beginning.

Let’s use The Sixth Sense again so I don’t have to spoil anything else. Bruce Willis’s death is a major emotional moment. If we were to plot it out, it’d be pretty high on our chart. It also comes very early in the linear structure. However, it’s revealed very late in the narrative structure. So his death comes at the correct point in the dramatic structure and fits the above pattern.

With me so far?

How about this. Let me be arrogant and use my own book. Ex-Heroes has nine major flashbacks in it, each one a full chapter long. However, each one follows the same dramatic structure. The flashbacks are increasing in tension even as the present day “Now” plot is increasing in tension.

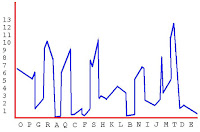

See, here’s the rough linear structure of Ex-Heroes. It begins with the rise of the heroes, followed by the rise of the zombies. About halfway through, you can see the peak of the outbreak where humanity falls and Stealth and St. George found the Mount. The narrative begins on page one of the book and around L on the graph. Once you look at these two sections (past and present) at the same time, with all the flashbacks happening where they do in the story, you see that the entire narrative fits the dramatic structure. I told a story with the linear structure I needed for the narrative structure I wanted to use, which gave me a solid dramatic structure.

See, here’s the rough linear structure of Ex-Heroes. It begins with the rise of the heroes, followed by the rise of the zombies. About halfway through, you can see the peak of the outbreak where humanity falls and Stealth and St. George found the Mount. The narrative begins on page one of the book and around L on the graph. Once you look at these two sections (past and present) at the same time, with all the flashbacks happening where they do in the story, you see that the entire narrative fits the dramatic structure. I told a story with the linear structure I needed for the narrative structure I wanted to use, which gave me a solid dramatic structure.

Make sense?

Let’s take a look at another chart. Yeah, IBM paid all that money, we should keep using them. This one’s where things go wrong, though.

It’s that exact same linear A through T story from up above, but now I’ve decided to tell it with a flash-forward near the beginning and a flashback just before the big climax. Look carefully– it’s all the same points, just in a new order.

It’s that exact same linear A through T story from up above, but now I’ve decided to tell it with a flash-forward near the beginning and a flashback just before the big climax. Look carefully– it’s all the same points, just in a new order.

See, in this example, all the structures are fighting each other. This is a story where the linear structure already matched the dramatic structure, so this new narrative structure doesn’t work. The dramatic structure’s broken, and this usually means the writer has broken the story’s flow. And we all know that’s bad.

When you look at it like this, it’s easy to see why too many frames and flashbacks start to make a jumbled mess of things when they get overused. Suppose my linear structure is that standard A though T again, which means my dramatic structure is, too. Look what happens when randomly rearrange these story points into something like our now-classic Mnbv Cxzlkjhgf Dsapoiuy Trewq order. The dramatic waves become a jagged, roller-coaster mess of different highs and lows that’s impossible to keep track of.

Look what happens when randomly rearrange these story points into something like our now-classic Mnbv Cxzlkjhgf Dsapoiuy Trewq order. The dramatic waves become a jagged, roller-coaster mess of different highs and lows that’s impossible to keep track of.

To be more specific, the whole thing becomes static.

And static’s just another word for noise we all ignore.

Y’see, Timmy, this is why so many would-be gurus take the easy route and say never to use flashbacks or any other narrative devices. Far too many writers will throw in a flashback (or two or three or five or…) that explains something in the story but doesn’t fit the dramatic structure. The fact gets out, but the story grinds to a halt in the process. Heck, sometimes you don’t even get a vital fact, just a bunch of random over-description that’s supposed to pass as character stuff. So gurus and other “experts” will tell you to avoid frames and flashbacks because it’s easier to say “don’t” then to explain how to use them correctly.

Which, hopefully, I just did. For free, no less. Even with all those high-end graphs.

Next time… well, after all this, I need to relax a bit. I’ll probably just harp on spelling again or something like that.

Until then, go write.