Enough holiday stuff for now. Let’s get back to what you’re all really here for—the thing you specifically came here for. Half-assed writing commentary! That’s the deal, right? You keep showing up, I prattle on for far too long and maybe make one or two useful points.

Which is, ho ho ho, what I wanted to talk about.

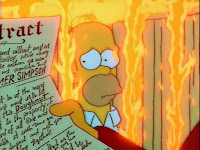

The act of telling a story is sort of an unspoken agreement between two people. Kristi Charish has called it “the invisible handshake.” As audience members, we expect certain things from our story. As storytellers, we expect certain things from our audience. When we sit down together, even if we’re separated by a few months and a printed page, we’re both assuming the other half of this experience is going to follow certain conventions.

So let’s talk about this contract between writer and reader. Or storytellers and audience, if you’d like to keep it a little broader. I think this agreement is kind of universal in that regard.

As the writer, what am I promising you?

This Is Readable

I think we can all agree books come with different levels of reading difficulty. They get aimed at different age groups or demographics. So it’s not impossible to believe we could stumble across a book that seems too simple or too difficult for us.

But this should never be my goal as a writer. Nobody should struggle to get through a book, fighting through convoluted, never-ending sentences filled with obscure words that describe dozens of irrelevant characters. And if I’m writing specifically to exclude people (“Only the people who really understand art will enjoy this…”) I’m doing this wrong. If you pick up one of my books, I want you to feel welcome, and to actually enjoy the act of reading it.

This Makes Sense

It doesn’t matter if my book’s set on a cruise ship, in a Victorian mansion, or on a space station—it has to have an internal logic. Characters need to make decisions and take actions that fit within their world and their personal experience.

A simple test I always try to give myself is “would this book be enjoyable to read again?” If twists aren’t earned, if betrayals aren’t set up, if explanations don’t line up with what I’ve said before this… my story probably doesn’t make sense. And you deserve better than that as a reader.

This Finishes Arcs

Nobody likes getting to the end of a book and finding out ha ha maybe everything will get answered in the next book. If we’re going to get immersed in a story, one thing we’re inherently expecting is some kind of resolution at the end. That sense of closure is a natural part of storytelling. We expect the heroes to have a final showdown with the villains, for this year’s Hunger Games to end, or for them to perform the last exorcism. And when they don’t and everything’s left unresolved… it just doesn’t sit right.

And sure, there might be dangling threads or even an overall arc that needs to continue. But when we get to the end of this story we expect, well, an ending. Some aspect of this story has to be done and wrapped up in a satisfying way (to the reader if not the characters)

This Was Worth It

This is a twofold thing. One ties back to an idea I’ve mentioned before—we want our hero to win, even if it’s a pyrrhic victory. We need to see them have some level of success, because if not we’ve just read a book where the hero, the person we’re supposed to relate to and empathize with… loses. Or doesn’t do anything. Or just has a textbook ending we’ve seen dozens of times before. After three hundred or so pages, these things can really make a book feel like it wasn’t worth reading.

Two is that, well, we want to feel like it was worth it financially. Nobody likes shelling out ten or fifteen bucks for a book that just wasn’t their thing, but shelling out that much for a book that’s incoherent, filled with typos, and half-copied from an old Doctor Whoplot? And then has a bad ending? I mean, even a buck can feel like too much for something like that. If I’m trying to get you to give me money for this story, this story should be worth money.

In my opinion, that’s all the big promises we’re expecting on the writer side of things. Yeah, there might be more expectations depending on the genre, the author, the intended audience, but I think this is probably a good contractual boilerplate. From this direction.

Coming from the other side of the negotiating table, what should I expect from my storytelling audience? If someone’s willing to engage with the story, there should be a few basic things they’re promising me, the storyteller. Things like…

The Benefit of the Doubt

If I’m going to pick up a book, I should at least begin with the basic assumption the writer knows what they’re doing. They meant to use this word or that term, and yeah, there’s a reason these people have a collection of HD-DVDs and not Blu-rays. If something isn’t clear on page two, I should be assuming there’s a reason things aren’t clear on page two, not that the writer has somehow screwed up telling their story.

This doesn’t mean there can’t be problems in those first few pages or minutes. But if I see something I don’t understand I shouldn’t be immediately labeling it as a mistake or a problem and using that to guide my ongoing interpretation of things. There’s a term for that—it’s called hatewatching.

The Time to Tell Their Story

Related to the above, if I pick up a murder mystery, I shouldn’t be complaining that we still don’t know who the murderer is in chapter three. Those two cute folks may not have kissed by page forty-two. There’s a good chance the aliens’ true motives could still be unclear a third of the way in.

Stories take time to unfold. We need build-up. We need to establish things. Some narrative devices just won’t work at certain parts of a story. If I’m reading a book, I need to be willing to accept that not everything’s going to be given to me in the first hundred pages—and that’s okay.

Judging It for What It Is, Not What I Want It to Be

It’s not uncommon to pick up a book not being 100% sure of what it is. What I thought was a sci-fi story might be more of a horror novel. This romance might involve a lot of historical drama. This superhero book might really be more of a superpowers thing. And sometimes this shift of genres and/or perspectives might be really annoying for us as readers.

But that doesn’t make the story wrong. Maybe it was poorly marketed or maybe I just don’t like horror novels. Maybe I wanted Dot to find true love or Yakko to go on a revenge-fuelled killing spree, and neither of these things happened in the book. But these things aren’t inherently flaws in the story. The writer told story A, it isn’t wrong because I wanted story B.

That’s what I think we should be expecting from the other half of the contract. And again, we could probably add other things depending on the book, the genre, the author. That’s why contracts get adjusted. This is, as I mentioned before, the basic starting form that you get for free on the internet.

And I’m sure some of you think this has just been some silly, meta-writing thing that you skimmed over. But y’see, Timmy, when this doesn’t happen—when one side or the other breaks the contract—we get frustrated. As audience members, we hate it when we need to struggle through a story, not getting the relevant details or getting buried in irrelevant ones. As authors, we grind our teeth when someone gives negative criticism because “I didn’t know this was a horror novel” or “I quit reading after three chapters” or “Amazon delivered this with a folded cover.”

Okay, that last one has nothing to do with our storytelling contract, but we all still grind our teeth when we get a one star review for that kind of nonsense.

So remember the contract. Make sure you’re holding up your end of it. Because nobody wants to be known as the person who breaks it. That’s just not a good look from either side.

Next time… well, I want to talk about what you’re not getting for the holidays.

Until then, go write.