I spent time at a few conventions last year and, as I do, I tried to get lots of photographs of the various cosplayers there. I’m always blown away by that sort of thing. I worked in the film industry for years and it’s amazing to see so many folks who are so dedicated they can do costumes that are on par (or better, in some cases) than the ones that end up on film.

Alas, one or two of my shots were spoiled by photobombers. You know that term, right? The folks who decide to lean into a picture and draw attention to themselves with a goofy grin or thumbs up, even though it’s really clear they’re not who the photographer wants things focused on. If you’re Chris Pratt, Hayley Atwell, or William Shatner and you end up photobombing somebody—hey, power to you. How fantastic would that be, looking at your pictures later and finding Hayley Atwell smiling and waving at you?

Alas, one or two of my shots were spoiled by photobombers. You know that term, right? The folks who decide to lean into a picture and draw attention to themselves with a goofy grin or thumbs up, even though it’s really clear they’re not who the photographer wants things focused on. If you’re Chris Pratt, Hayley Atwell, or William Shatner and you end up photobombing somebody—hey, power to you. How fantastic would that be, looking at your pictures later and finding Hayley Atwell smiling and waving at you?

On the other hand, if I’m someone that’s going to make 99.9999% of humanity say “who the hell is that?”… I’m kind of being a jerk. Because I’m not supposed to be the focus of this picture. And by drawing attention away from what is supposed to be the center of attention, I’ve messed up this image.

Or, for our purposes, this story.

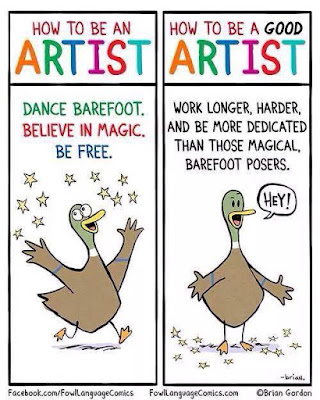

In some ways, being a writer is a thankless job. If I do it right, people shouldn’t even notice me. If I do a spectacular job, people should forget me altogether. Screenwriters get hit even worse with this—their work is often credited to the actors or director. The ugly truth of storytelling is that none of us really care about the storyteller, we just want to hear the stories.

Some storytellers try to get noticed. It’s a deliberate choice. They lean in and draw attention to themselves. They wink and point. Sometimes they make goofy expressions and shout “Look at me! Look what I’m doing!”

When I do this as a writer, it’s just like photobombing. Textbombing? Prosebomb? Whatever we want to call it, it’s me drawing attention away from telling my story, which—in theory–is supposed to be the focus of my writing.

Here’s a few simple ways I can make sure I’m not ruining my focus…

Vocabulary—Stephen King once said that “Any word you have to search for in the thesaurus is the wrong word.” And, personally, I think he’s completely right about that. I don’t think using a thesaurus is bad. I’ve got one right here on my desk. I often use it to jog my memory when I know there’s a specific word I’m looking for, and the easiest way to find it is to look up a synonym.

But some folks default to their thesaurus. They have a sentence—let’s say “The thin woman wore a red hat.”—and then just immediately go to find bigger, better words for it. That’s how you end up with sentences like… well…

But some folks default to their thesaurus. They have a sentence—let’s say “The thin woman wore a red hat.”—and then just immediately go to find bigger, better words for it. That’s how you end up with sentences like… well…

“The rawboned feminine figure accoutred her cranium with a chapeau of deepest carmine felt.”

That’s me, as a writer, trying to draw attention to myself when you, the reader, want to be focused on the story.

Any word I choose just to get attention, to prove I don’t need to use a common, blue-collar word, is the wrong word. Any word that makes my reader stop reading and start analyzing is the wrong word. I can try to justify my word choice any way I like, but absolutely no one is picking up my manuscript

hoping for a vocabulary lesson. When my reader can’t figure out what’s being said for the fourth or fifth time and decides to toss said manuscript in the big pile on the left… there’s only one person to blame.

Like I said, I’ve got a thesaurus on my desk. But it’s not right here in arm’s reach, like the dictionary. It’s a shelf up and off to the side. Just enough that I really need to stand up to get at it. And move some LEGO people.

Structure—A friend of mine is really into cirque school. I’ve seen her do some of those aerial silk tricks where she’ll climb to the top of the studio, wrap her legs, bring the silk around her body, and then sort of roll down the silk. She spins and the silk twirls all around her and it takes two or three minutes for her to work her way back down to the floor. I’m sure most of you reading this have seen some version of this, either live or maybe on television. Its really beautiful and amazing when done right.

It’s also—and she’d be the first to admit this—a really inefficient way to get from point A to point B. And taking even longer to do it, well, that just gets exhausting for the performer and the audience. None of us have the stamina for that kind of thing. Getting there is half the fun, absolutely, but the point of most trips is still getting there.

When the trip itself becomes the focus, it means my goals have shifted. Getting to point B isn’t the important thing anymore. And since storytelling is, in essence, getting characters from point A to point B… well…

If I think of my story as an A—B line (to fall back on geometry), how often does my chosen structure

deviate off that line? How many times does it not move along the line at all? How often does it go backwards?

And how much of this is because of how I’ve chosen to structure things?

I’ve seen people write page-long sentences which serve no purpose except to be a page-long sentence. Sure, it’s very impressive in an MFA, grammatical-accomplishment kind of way, but past that… does it really advance the story? Is it pushing the narrative, or just pushing the fact that I sat through half a dozen classes on creative writing?

If I’m overloading my story with

flashbacks, a non-linear plotline, or twenty-two points of view… what am I hoping to accomplish? Are they adding anything? Would it honestly lessen the story to not have them? Or am I just adding in gimmicks that

I’ve heard make a story betterwithout any real understanding of how or why they work?

Said

Said—I’ve mentioned this a few times. People will never notice if you use

said. Honest, they won’t.

Saidis invisible. What they notice is when my characters retort, respond, pontificate, depose, demand, declare, declaim, muse, mutter, mumble, snap, shout, snarl, grumble, growl, bark, whimper, whisper, hiss, yelp, yell, exclaim, or ejaculate. Yeah, ejaculate. Stop giggling, it was

a common dialogue descriptor for many years. Once I’ve got three or four characters doing this all over the page, I shouldn’t be too surprised if my audience stops reading to shake their heads or snicker.

Now, granted, there are times where my characters will be hollering or whispering or snarling. And when that happens, I don’t want my readers to already be bored by my constant use of different dialogue descriptors.

I want it to count. Overall, they’re just going to be saying stuff. So I shouldn’t overcomplicate things and draw attention to myself.

These are just a few things to watch for in my writing, granted. There’s always going to be that person who finds a clever new way to draw attention to themselves. And

there will always be exceptions, sure. Really, though, photobombing my own story isn’t going to be a winning strategy.

Never forget… first and foremost, people are showing up for the story.

Quick note, before I forget. If you happen to be in the Los Angeles area, this weekend I’m hosting the Writers Coffeehouse at

Dark Delicacies in Burbank on Sunday. It’s three hours of writers talking about writing, it’s open to everyone, and it’s free. Stop by and talk. I guarantee it’ll be highly adequate.

Next time, I’d like to talk about a big car accident I was in many years back.

Until then, go write.

Just don’t be seen doing it.

Alas, one or two of my shots were spoiled by photobombers. You know that term, right? The folks who decide to lean into a picture and draw attention to themselves with a goofy grin or thumbs up, even though it’s really clear they’re not who the photographer wants things focused on. If you’re Chris Pratt, Hayley Atwell, or William Shatner and you end up photobombing somebody—hey, power to you. How fantastic would that be, looking at your pictures later and finding Hayley Atwell smiling and waving at you?

Alas, one or two of my shots were spoiled by photobombers. You know that term, right? The folks who decide to lean into a picture and draw attention to themselves with a goofy grin or thumbs up, even though it’s really clear they’re not who the photographer wants things focused on. If you’re Chris Pratt, Hayley Atwell, or William Shatner and you end up photobombing somebody—hey, power to you. How fantastic would that be, looking at your pictures later and finding Hayley Atwell smiling and waving at you? But some folks default to their thesaurus. They have a sentence—let’s say “The thin woman wore a red hat.”—and then just immediately go to find bigger, better words for it. That’s how you end up with sentences like… well…

But some folks default to their thesaurus. They have a sentence—let’s say “The thin woman wore a red hat.”—and then just immediately go to find bigger, better words for it. That’s how you end up with sentences like… well… Said—I’ve mentioned this a few times. People will never notice if you use said. Honest, they won’t. Saidis invisible. What they notice is when my characters retort, respond, pontificate, depose, demand, declare, declaim, muse, mutter, mumble, snap, shout, snarl, grumble, growl, bark, whimper, whisper, hiss, yelp, yell, exclaim, or ejaculate. Yeah, ejaculate. Stop giggling, it was a common dialogue descriptor for many years. Once I’ve got three or four characters doing this all over the page, I shouldn’t be too surprised if my audience stops reading to shake their heads or snicker.

Said—I’ve mentioned this a few times. People will never notice if you use said. Honest, they won’t. Saidis invisible. What they notice is when my characters retort, respond, pontificate, depose, demand, declare, declaim, muse, mutter, mumble, snap, shout, snarl, grumble, growl, bark, whimper, whisper, hiss, yelp, yell, exclaim, or ejaculate. Yeah, ejaculate. Stop giggling, it was a common dialogue descriptor for many years. Once I’ve got three or four characters doing this all over the page, I shouldn’t be too surprised if my audience stops reading to shake their heads or snicker.  Back in 1989 (just around the time I was questioning my professor about Brown’s book), Robin Williams gave an interview where he talked about a production of Waiting for Godot that he’d been in with Steve Martin the year before. “I dread the word ‘art,’” Williams told the AP. “That’s what we used to do every night before we’d go on with Waiting for Godot. We’d go, ‘No art. Art dies tonight.’ We’d try to give it a life, instead of making Godotso serious.”

Back in 1989 (just around the time I was questioning my professor about Brown’s book), Robin Williams gave an interview where he talked about a production of Waiting for Godot that he’d been in with Steve Martin the year before. “I dread the word ‘art,’” Williams told the AP. “That’s what we used to do every night before we’d go on with Waiting for Godot. We’d go, ‘No art. Art dies tonight.’ We’d try to give it a life, instead of making Godotso serious.”