December 17, 2009 / 4 Comments

Dating Tips

December 11, 2009 / 4 Comments

I Put The Poison In Both Cups

Easy geek reference up there for you.

So, this week’s little rant is sliding in under the wire. To be honest, I’ve been buried under a ton of last-minute stuff for work. Plus the holidays. Plus some family stuff. I can’t be expected to keep up on all of it.

Well, that’s not true. It’s a bit of a cop-out, really. If I’d managed my time a bit better a lot of this would’ve been done on time. There were even two or three times this week I remember thinking “I need to start working on this week’s ranty blog post.”

Cop-outs suck, don’t they? You’ve made an investment in some piece of writing and then wham! Out of nowhere the writer just does something lame. They’ll change the rules or deliberately ignore continuity and just try to bluff their way through. Epic stories that don’t deliver. Mysteries that aren’t explained. Ominous foreshadowing that never pays off. All of these are cop-outs.

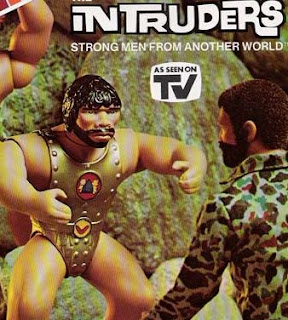

The very first story I can ever remember telling had a cop-out ending. I was about eight years old, it was summer, and Mom had taken us to the beach even though I wasn’t feeling well. Somehow I ended up sitting with the father of my friend Todd, while everyone else played in the water, and I spent the time regaling him with the epic tale of G.I. Joe fighting off the Intruders.

For those of you born after 1980, G.I. Joe used to be just shy of a foot tall and had fuzzy hair. You could even shave him. He was also firmly grounded in the real-world military. When Star Wars shifted the toy paradigm to science fiction, GI Joe suddenly gained a bunch of new friends, like the superhero Bulletman and the cyborg Mike Power. And enemies called the Intruders which were a race of alien bodybuilder midgets who  wore metal leotards… sort of…

wore metal leotards… sort of…

Anyway, on with the story.

You see, the Intruders came down in asteroids. And they all crash-landed at GI Joe’s secret base. There were lots and lots and lots of them. In fact, there were a million of them. So GI Joe was shooting at them with his gun and he shot ten of them, and Mike Power was kicking with his bionic leg–

(Mike Power had one bionic leg. Just one. Even at the age of eight, I could see the gigantic flaws in this bit of cybernetic engineering.)

–and Bulletman used his ray to lift a bunch of them into the air and send them away. This pattern of violence was repeated enthusiastically twice or thrice before I declared all the Intruders defeated.

Not so, Todd’s father told me. A million is a lot.

I conceded this, and explained that the above mentioned pattern of gun-kick-ray happened again. So now they were all gone.

No, he said with a smile and a shake of his head, a million means there’s a lot more left.

I nodded, then said that Bulletman had used his ray to scoop up everyone who was left and send them away.

It seemed like a very solid ending at the time.

Granted, it’s easy to excuse an ending like that from an eight year old, but far too many adults use them, too. Except for poor spelling, there isn’t a much more glaring sign of poor writing than a plot thread that winds up with a cop-out. It shows the writer didn’t think things out, or just couldn’t be bothered to.

A few common types of cop-outs.

Changing the rules–While it completely fits the story it’s told in, the title reference of this little rant is a perfect example of changing the rules. In the midst of this serious contest of life and death, we find out it wasn’t a fair contest. We’ve been told within the story that X + Y = Z, but the writer suddenly announces X + Y can also equal Q. This usually comes about because the story has been written into a corner and the writer won’t take the time to go back and change things (when the ancient Greeks did this, they called their cop-out deus ex machina). As Billy Wilder once observed, a problem in your third act is really a problem in your first act.

Changing the rules is inconsistent and it breaks the flow. William Goldman used it for comedic effect in The Princess Bride, but it’s doomed to almost certain failure in anything except a comedy. Heck, thanks to Goldman it’s going to look pretty tired in a comedy, too…

The so-called twist–This is a more specific type of changing the rules. I’ve set out the rules for a good twist before, and they’re pretty simple for anyone to figure out. That’s why it’s so frustrating when a writer has Debbie pull off her wig and announce “Hah!! I’m really Larry’s second-cousin!!!” This is often followed by flipping through pages to figure out who Larry is and why his second cousin would have it in for everybody.

Usually a poor twist tries to solve one problem in the story at the expense of the story itself. A weak twist isn’t just a cop-out for a plot thread, it’s almost a guarantee the manuscript will end up in the large pile on the left.

No payoff –Few things are as annoying then to go through a story waiting to see the two enemies clash or to learn the answer to the mysterious puzzle that’s plagued out heroes… only to not get it. The enemy gets away. The mystery gets skirted over. It just leaves the reader feeling cheated.

Sometimes it’s not even a question that’s not answered, it’s just a payoff that never happens. When the climactic, world-altering final battle occurs off-camera and we just see the characters talking afterward about how amazing it was, that’s a cop-out.

Just plain weak–– Sometimes when a writer uses a cop-out, they’re just choosing the path of least resistance. It’s quick and easy and wraps stuff up. Oh, he was dreaming and she was insane. Sometimes an ending can seem solid, but it’s still weak because of the promise of something bigger. A worldwide alien invasion is awesome. A worldwide invasion where the aliens can be defeated by tap water… not so much. Remember, a story can be weak by inclusion just as much as by omission.

And there you have it. I’d put more, but, as I mentioned before, I have a lot of work to do still.

Plus, I’m really Larry’s third cousin.

Still open to suggestions as we head into the holidays. If not, next time I’ll end up blathering about women I’ve dated or something.

Until then, go write. At least your Christmas cards.

December 3, 2009

The Return of The 3-D Man!!

I’d love to say there’s more to this pop-culture reference than just the number three, but I’d be lying.

Maybe.

So, it struck me a while back that I haven’t really prattled on about characters in quite a while. I’ve brought them up as kind of a sideline thing while talking about other story elements, but I haven’t focused on characters specifically. So I started thinking about them and why some come across so well on the page while others leave a reader cringing.

That got me thinking about Bob. To be honest, first it got me thinking about Yakko Warner, my usual example, but Yakko’s a pretty well-established character already. So I ended up with Bob, and wondering what could make him a good leading man for my action-adventure story about cyber-ninjas from the future.

If we want to make Bob the best character he can be, I think there are three key traits he needs to have.

First and foremost, a good character has to be believable. It doesn’t matter if said character is man, woman, child, cocker spaniel, Thark warrior, or protocol droid. If the reader or audience can’t believe in them within the established setting, the story’s facing an almost impossible challenge right from page one.

Bob has to have natural dialogue. It can’t be stilted or forced, and it can’t feel like he’s just the author’s mouthpiece, spouting out opinions or political views or whatever. The words have to flow naturally and they have to be the kind of words this person would use. I saw a story once where one high school jock said in amazement to another “You broke up with her via text?” Via? Is that even remotely the type of word or phrasing that would come out of a teenage football player’s mouth?

On a similar note, the same goes for Bob’s motives and actions. There has to be a believable reason he does the things he does. A real reason, one that makes sense with everything we know (or will come to know) about him. It’s immediately apparent, just like with dialogue, when a character’s motivations are really just a veiled version of the writer’s.

Also, please note that just because a character is based on a real person who went through true events does not automatically make said character believable. I’ve tossed out a few thoughts here about the difference between real-real and fiction-real, and it’s where many would-be writers stumble. They think because the amazing story they’re telling about Bob is true, it’s somehow valid. He really did this, therefore the reader must accept it. Alas, it just doesn’t work that way. Remember, there is no such thing as an “unbelievable true story,” only an unbelievable story.

Second, tied very closely to the first, is that a good character needs to be relatable. As readers, we get absorbed in a character’s life when we can tie it to elements of our own lives. We like to see similarities between them and us, so we can make extended parallels with what happens in their lives and what we’d like to happen in our lives. Luke Skywalker is a boy from a small town with big dreams (just like me) who goes off to join a sacred order of super powered knights (still waiting for that–but it might happen). There’s a reason so many novels and movies revolve around the idea of ordinary people caught up in amazing situations. Heck, Stephen King has made a pretty sizeable fortune off that basic premise.

Some of this goes back to the idea of being on the same terms as your audience and also of having a general idea of that audience’s common knowledge. There needs to be something they can connect with. Many of us have been the victims of a bad break up or two. Very, very few of us (hopefully) have hunted down said ex for a prolonged revenge-torture sequence in a backwoods cabin. The less common a character element is, the less likely it is your readers will be able to identify with it. If your character has nothing but uncommon or rare traits, they’re unrelatable. If Bob is a billionaire alien with cosmic-level consciousness who sees all of time and space at once and only speaks backwards in metaphor… how the heck does anyone identify with that?

Oh, but wait! I see a hand shooting up in the back. Watchmen has the all-powerful Doctor Manhattan, doesn’t it? Ahhhh, but y’see Timmy, one of the primary character traits we remember about him isn’t his omnipotence. It’s his awkward fumbling when he tries to interact with the people in his life. He’s the ultimate social outcast–trying to fit into a clique (humanity) he’s grown out of, and aware that every day he’s a little less a part of that group. He even acknowledges that losing his girlfriend–his last real connection with the clique–means he probably won’t even try to fit in anymore. If that’s not universally relatable, what is?

If readers can’t identify with Bob, they can’t be affected by what happens to him. Which brings us to our final point…

Third, a good character needs to be likeable. As readers and/or audience members, we have to want to follow this character through the story. Just as there needs to be some elements to Bob we can relate to, there also have to be elements we admire and maybe even envy a bit. If he’s morally reprehensible, a drunken jackass, or just plain uninteresting, no one’s going to want to go through a few hundred pages of his exploits… or lack thereof.

Keep in mind, this doesn’t mean a good character has to be a saint, or even a good person. The lead character of The Count of Monte Cristo is an escaped prisoner driven all-but-mad with thoughts of revenge who spends most of the book destroying the lives of several men and their loved ones. In Pitch Black, Riddick is a convicted mass-murderer who likes mocking all the people around him. Hannibal Lecter is a compelling, fascinating character on page and on the screen, but no one would ever mistake him for a role model. Yet in all these cases, we’re still interested in them as characters and are willing to follow them through the story.

A good character should be someone we’d like to be, at least for a little while. That’s what great fiction is, after all. It’s when we let ourselves get immersed in someone else’s life. So it has to be a person–and a life– we want to sink into.

Now, I’m sure anyone reading this can list off a few dozen examples from books and movies of characters that only have one or two of these traits. It’d be silly for me to deny this. I think you’ll find, however, the people that don’t have all three of these traits are usually secondary characters. Often they’re also stereotypes, too. The creepy neighbor, the gruff boss, the funny best friend, the scheming villain. They don’t need all three traits– three dimensions, if you will–because they aren’t the focus of our attention. They’re the bit players, so to speak, and a good writer isn’t going to waste his or her time pouring tons of energy into a minor character who has no real bearing on the story.

Yeah, up top when I said I was lying about the 3-D thing, I was lying. I do that.

So there you have it. Three steps to stronger, three-dimensional characters.

Next time… well, I’m running short of ideas again, so unless someone suggests a good topic, next week might be a bit of a cop-out.

Before I forget, a quick shout out to Brave Blue Mice, a fun little fiction ‘zine which asked to publish the RSS feed for the ranty blog on their site. For the record, no, I didn’t know what that meant when they asked, but Greg explained it to me in simple terms even a caveman could understand. Go visit, read some stories, and send him a few of your own.

And go write.

November 26, 2009

Time And Relative Dimensions In Space

Wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey.

This one’s just a quick thought before we all lunge into the holiday season.

Time is a tricky thing in stories. Oh, you’ve got the usual narrative time issues like skipping a few days here or there or going into a flashback, and I’ve prattled on about those a few times. There’s also continuity issues with time. Who knew what and when, was she with him at the same time she was with her, and how did he know that when he hadn’t met her yet–we’ve all dealt with these issues. Well, hopefully you’ve dealt with them…

I wanted to talk about a different aspect of time, though.

Time, and the passage of time in a story, tells us about characters. It gives us an insight when Yakko can shrug off losing a piece of jewelry after a long sigh but Dot is still crying about it two months later. It really tells us something when Wakko can’t remember what he had for breakfast yesterday and Marco can recite every item on the table from breakfast on his fourth birthday. If it takes Bob six months to hit the point where he’ll compromise his morals and Rob breaks after six hours, you know who you want to be trapped in the Andes with. How long something has an effect–or doesn’t have an effect–on someone tells us subtle thing about them that register just as much as any monologue they’re about to spiel out.

I was reading for a screenplay contest recently and came across an example of this in one script. On the off chance the contest entrant is reading this (slim, but let’s be polite), I’m going to tweak a few facts and relate the set-up more than the story. It was just such a perfect example of what I’m talking about.

We begin, as the header tells us, in May of 1999 as a stranger arrives in town. A local woman is mourning the death of her daughter, and she goes to the cemetary to set flowers on the grave. We see on the tombstone that her daughter died just over a month ago, in early April of ’99. That night, when she breaks down in tears over dinner, her husband sighs and tells her she has to get over it and it’s time she moved on.

When we see her in town the next day, most folks she meets are a bit stand-offish to her. Eventually she finds the stranger, they become friends and after another twenty pages or so she confesses how miserable she’s been since her daughter died… just over a year ago.

A quick check confirms both of the dates I’ve already mentioned to you. So which is the mistake? Was “year” supposed to be “month” or was one of the earlier dates wrong? Well, a few pages later she’s talking with a priest and the one year figure comes up again. So the problem was in the earlier dates, apparently.

A harmless typo, you say?

Well, here’s the thing. Her husband came across as kind of a jerk, didn’t he? His own daughter’s dead a month and he’s already telling his wife to move on? It didn’t matter how long she was supposed to be dead. All we have is the words on the page, and those words make us interpret and judge things in a certain way.

Look at this scene when you know it’s a year and suddenly the husband’s a much more sympathetic character. He’s barely recovered from one loss and is dealing with a wife it looks like he might lose to her own grief. Same with those townspeople. They seem a bit cold to ignore a grieving mother, but it’s a bit understandable why many of them might be put off by a woman who’s been grieving for close to thirteen months.

All that messed up in the story because of a single digit.

What this means for us as writers is that we need to be really, really careful with time and dates. They need to be double and triple-checked. Unlike a typoed word, I can’t tell if a date is wrong or not. “Birthday cale” is an easy-to-spot mistake, but “2005” is not.

Y’see, Timmy, the immediate, unconscious timelines those dates and times create are something we can all key into, and we can relate to them (and make judgements off them) almost immediately. They set up certain assumptions and conceptions about characters, and if they’re the wrong ones it can land your script in that big pile on the left.

So, as the Doctor always says, please be careful when you play with time.

Come back next week at our usual bat-time, and you can listen to me prattle on about characters.

Until then, go write. And have a Happy Thanksgiving.