Very sorry about missing last week. Copyedits. And Thanksgiving is this week, so I know nobody’s going to be reading this on Thursday. So I figured I’d get this up today and hope to break even. Sort of…

Anyway, this week I wanted to blab on about dating your work. And I figured the best way to do that would be to talk about the Cat & Fiddle.

If you’re not familiar with Los Angeles, the Cat & Fiddle has been a Hollywood landmark for about thirty years now. It’s a little pub in the middle of Hollywood with a nice outdoor patio. It’s always been popular, but I think it managed to avoid being hip or trendy in all that time. Part of Casablanca was filmed on that location. Seriously.

Heck, there’s a reference to the Cat & Fiddle about halfway through my book, 14. It was a landmark, as I said, and my story is very much about Los Angeles. Why wouldn’t I refer to it?

Except now it’s closing. The landlord found someone willing to pay twice as much so, well, the cat’s out in the cold. No more Cat & Fiddle unless they can find a new place. Somewhere else.

Just like that, 14 has become dated.

Still, I’m not as bad off as James P. Hogan. When he wrote his novel Inherit the Stars (first book in the Giants series) back in 1977, he envisioned the US facing off against the Soviet Union in a race to colonize the solar system (a race that gets interrupted by an amazing discovery, granted…). Needless to say, the first three books in that series are extremely dated.

Still, I’m not as bad off as James P. Hogan. When he wrote his novel Inherit the Stars (first book in the Giants series) back in 1977, he envisioned the US facing off against the Soviet Union in a race to colonize the solar system (a race that gets interrupted by an amazing discovery, granted…). Needless to say, the first three books in that series are extremely dated.

When we say a book is dated, we mean it’s a book someone can look at and say “Ahhh, well this was clearly written back when…” It’s a book that isn’t about now, it’s about then. And when my book’s not about now, that’s just another element that’s making it harder for someone to relate to my characters and my story.

Remember in school when you had to read classics? Some of the hardcore Dickens or Austen or maybe even Steinbeck. One of the reasons they can be hard to read is because of the references in them. They talk of events or customs or notable persons that are foreign to us. Hell, half the time so foreign they’re just gibberish (bundling? What the heck is bundling..?).

When we hit these stumbles, it breaks the flow and makes the book harder to enjoy. A dated book has a shelf life, like milk or crackers. The moment it gets this label, there’s an end in sight.

Because of this, there’s a common school of thought that I shouldn’t make any such references in my work. My story shouldn’t mention current fads or events. I don’t want to have references to celebrities or television shows or bands or music. If I want to have my writing to have any sort of extended life—the “long tail” as some folks like to call it—it can’t be dated.

And there is something to this. I’ve seen metaphor-stories fall flat with readers less than a year after the events they’re referencing. It was funny at the time, but if you watch Aladdin today it’s tough to figure out half the stuff the Genie’s riffing on (what the heck’s with the whoop-whoop fist thing…?).

However…

When the GOP shut down the US government last year, my friend Timothy Long pounded out a longish comedy short story called Congress of the Dead. And for a few months it sold really, really well. It’s not doing much these days (it’s still funny but not as topical), but he knew going in that it wasn’t going to be timeless and used that knowledge to his advantage.

So, which way should I go?

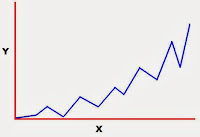

Well, here’s the catch. My work is always going to end up dated. Always. There’s no avoiding it. Stories get dated by technology and cars and geography. Things people assume will never change (like the Cat & Fiddle or the U.S.S.R.) end up changing. It happens all the time. It can’t be helped.

Consider this…

Stephen King’s Cujo couldn’t happen today. Cell phones undermine the entire plot. Same with Fred Sabehagan’s Old Friend of the Family. The entire plot of Lee Child’s first Jack Reacher book, Killing Floor, hinges on an idea that was obsolete six months before the book even reached stores.

Let’s not even talk about speculative fiction. How many sci-fi shows predicted events we’ve since caught up with and passed? Buck Rogers left Earth on a deep space probe in 1987, and Thundar the Barbarian saw the world collapse in 1994. Star Trek told us the Eugenics Wars happened in the 1990s, which was also when Khan and his followers were launched into space in cryogenic suspension (presumably using the technology from the Buck Rogers deep space probes). According to the Terminator franchise, Judgement Day happened in 1997 (later adjusted to 2004). Then there’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and it’s sequel 2010. Heck, even Back to the Future is just a few short weeks away from becoming a silly, dated comedy. It’s going to be 2015 and there are no self adjusting clothes or flying cars or Jaws XIX (it looks like we did get hoverboards, though…). And, hell, supposedly in 2015 people are still using faxes as a high-tech method of communication.

If I really don’t want to date my work, I can’t mention anything. Cars, music, movies, television shows, networks, books, magazines, sports teams, games, cell phones or providers, Presidents, politicians, political parties, countries, businesses of any kind, actors, actresses… all these things and a few dozen more. All these things change all the time in unpredictable ways. So if I want to be timeless, I can’t bring up any of them.

The problem is, though, these are all things that are part of our lives. They come up in conversations. They shape how we react to other things. So if I’m writing a realistic character with natural dialogue… these things will be there.

So what’s this all mean?

In the big scheme of things… don’t worry about it.

That being said, I probably shouldn’t base my entire plot around readers knowing the lyrics to Taylor Swift’s latest single, and (much as I love it) I might not want to use a reference to the second season finale of Chuck as the big button on my chapter. There’s a reason some things stand the test of time, some become cult classics, and others become… well, we don’t know, do we? And I should never be referencing something no one knows about.

There isn’t an easy answer for this. I’d love to list off some rules or just be able to say “8.3 references per 50 pages is acceptable,” but it isn’t that simple. A lot of this is going to be another empathy issue. As a writer, I need to have good sense of what’s sticking around and what’s a fleeting trend. What references will people get in ten years, which ones they’re going to forget in six months, and how blatant these references need to be to get the job done.

Getting dated is unavoidable. It is going to happen to my work. And yours. And hers. But if we’re smart about it, we can get the most out of it while we can and still make sure that date’s as far off as possible.

Next time, I’d like to talk about dialogue. And I’ll probably make a mess of it.

Until then… go write.