And I’m going under the general assumption that if you’ve slogged through all this, you’ve got at least a basic grasp of this writing thing and are hoping to go further with it. Perhaps even make a few dollars with it. And if any of you have a specific question or topic you’d like me to prattle on about, let me know.

Category: rules

January 5, 2012 / 4 Comments

Why Are We Here?

And I’m going under the general assumption that if you’ve slogged through all this, you’ve got at least a basic grasp of this writing thing and are hoping to go further with it. Perhaps even make a few dollars with it. And if any of you have a specific question or topic you’d like me to prattle on about, let me know.

January 15, 2010 / 1 Comment

The Golden Rule

Just to be clear up front, this is not about doing unto others. Sorry.

When I started this blog way, way back in the dusty year of 2007, there wasn’t much to it. To be honest, it really started as a column I was pitching to one of the editors at Creative Screenwriting. If you look back at some of those early posts you can still see that more formal edge to them. Anyway, I pitched the idea and a few sample columns to one editor, then to the editor that replaced him, and then casually to the publisher once at a party. Then I said screw it and tossed them up at Blogspot under the best name I could come up with in fifteen seconds. Where they sat for many months until I decided I wanted to spew about something else I was seeing new writers doing. I think I’d just finished reading for a screenwriting contest and was just baffled how so many people could keep making the same mistakes again and again.

It was also about the time I was giving up crew work in the film industry to start writing full time. It meant I was browsing a lot of other blogs and message boards. It struck me that while there were all-too-many folks offering “useful advice” about getting an agent, submission formats, publishing contracts, and so on, there were very few that offered any help with writing. Which seems kind off bass-ackward, as old folks say to young folks. Also, the few folks that were speaking about writing tended to do so with absolute certainty, despite a lack of credentials of any sort whatsoever. Worse still, a huge number of people were blindly following those folks and their bizarre “rules” of writing..

Now, I did lots of writing stuff as a teenager, but it wasn’t until college that I discovered how many markets there were, and how many magazines devoted to the craft of writing. Again, old fashioned as it may make me sound (granted, there was a different guy named Bush in the White House then), this pile of magazines did something the internet doesn’t. It actually forced me to learn the material rather than just plopping it in front of me. I had to search every article, every column, and read through them in their entirety hoping to find a hint or tip on how to improve my writing skills.

One thing that became apparent pretty quick, even to not-yet-legal-to-drink me, was that a lot of these tips contradicted each other. Here’s an article about how you should write eight hours a day, but this one says four, and that one says don’t write unless you’re inspired. She says to outline and plot out everything, he says to just go with the flow and see what happens. One columnist suggests saving money by not asking for your submission back, but another writer points out that this creates the instant mental image that your manuscript is disposable.

Y’see, Timmy, if you ask twenty different novelists how they create a character, you’re going to get twenty different answers. If you ask twenty screenwriters how they write a scene, you’re going to get twenty different answers. And all of these answers are valid, because all of these methods and tricks work for that writer.

Which is the real point of the ranty blog. I want to offer folks some of the tips and ideas I sifted out of all those articles and columns, along with some I’ve developed on my own after trying (and failing and trying again) to write a hundred or so short stories, scripts, and novels.

To be blunt, I don’t expect anyone to follow the tips and rules here letter for letter. Heck, as I’ve said before, I don’t follow all of them myself. I sure as hell wouldn’t call it a sure-fire way to write a bestselling novel or anything like that, because writing cannot be distilled down to A-B-C-Success. The goal here is to put out a bunch of methods and advice and examples which the dozen or so of you reading this can pick and choose and test-drive until you find (or develop) the method that works best for you. That’s the Golden Rule here.

What works for me probably won’t work for you. And it definitely won’t work for that guy.

There are provisos to this, of course. Not everything about writing is optional. You must know how to spell. You must understand the basics of grammar. If you’re going into screenwriting, you must know the current accepted format. A writer cannot ignore any of these requirements, and that is an absolute must. Past all that, you must be writing something fresh and interesting.

I think this is where most fledgling writers mess up. They assume it’s all-or-nothing. Not only do you have the artistic freedom to ignore the strict per-page plot points of Syd Field or Blake Snyder, you can actually ignore plot altogether. You’re also free to ignore motivation, perspective, structure, and spelling.

It doesn’t help that there’s a whole culture of wanna-bes out there encouraging this view because… well, I can only assume because they’re too lazy to put any real effort into their own writing. If they get everyone else doing it, then it means they’re not doing anything wrong.

To take veteran actress Maggie Smith slightly out of context (she was talking about method actors): “Oh, we have that in England, too. We call it wanking.”

Anyway, I’m getting off topic. I hope I’ve made it clear what the cleverly-named ranty blog is about, and that most of you will still tune in next week to see what I decide to prattle on about.

Speaking of which, next week I wanted to talk about prattling on.

Until then, go write.

March 21, 2009 / 1 Comment

No Exceptions. None. Usually.

A week or three back I was browsing over the responses I get here. Luckily there’s only six or seven of you reading this, and I’m sure you’re all busy writing your own stuff, so it didn’t take long.

Anyway, I noticed an interesting thing. One of the most common forms of response here was the “Ahhhh, but…” They weren’t as emphatic or strongly worded as some of the ones you often find on most message boards, but they were there. Salt and peppered throughout the ranty blog.

If you can’t figure it, the “Ahhhh, but…” response is when someone counters a point with contradictory information. For example, I could say “Writing a blog will never help you get a film deal,” and someone could leap forward and say “Ahhhh, but isn’t that just what happened to Diablo Cody, writer of Juno? Not so smart after all, are you, Mister-wise-writer-guy?”

In even simpler words, the “Ahhhh, but…” response is when people point to the exception in an attempt to disprove the rule. Usually, they’re doing this to show that someone else did it the easy way, so we can’t fault them for trying to do it the easy way as well.

Now, let’s be clear on one thing—there are always exceptions to the rule. Always. Anyone who tells you that something is 100%, never-question-it always wrong can be ignored. Especially if they shriek “no exceptions!!”

Here’s the catch… exceptions to the rule are very, very rare. Exceptionally rare, you could say. That’s why they’re the exception and not the rule. For every person who sold the first draft of the first novel they wrote, there are millions of people who did not. Yeah, Kevin Smith got into Hollywood with a successful, low-budget indie film, but tens of thousands of folks have tried the same trick with no results. And, yes, Diablo Cody made a screenwriting career out of her blog—and that’s one out of how many blogs on the internet? One out of ten million? Fifty million? More?

That’s why most people trying to give you useful information, like myself, tell you to stick with all the established rules. It’s a longer, harder, and more frustrating path, but it’s still your best bet at success. Sure, I could sound a lot more positive and cheerful a lot of the time. I could say everyone’s a special snowflake, don’t worry about doing things wrong, and we should just do what feels good because we’ll all get published or produced some day. The overwhelming odds are, though, that I’d be doing all of you a disservice with such statements.

So, here’s my bit of advice for you, and it’s one I hope you’ve seen underlying most of the stuff I’ve said here since the first post you may have read.

The best thing you can do is assume you are not the exception to the rule. No matter how clever, how witty, how perfect your writing is, do not think of yourself as the one person who gets to ignore all the established standards. The absolute worst thing you can do is scoff at the rules and think they don’t apply to you. No matter how vastly superior your work is, always consider yourself working from the same level as everyone else.

The reason you should assume this is because the person reading your work is going to assume it. Nobody goes to a Friday the 13th film thinking it’s going to have an Oscar-winning metaphor for the Israel-Palestine conflict in it. You don’t pick up a Stephen King book for a tearjerker romance. And, personally, I’d be a bit shocked if Charlie Gibson decided to perform the ABC Evening News as an opera some night. We all have certain expectations we’ve built up, and these expectations all tend to fall in line with the rules.

Does that mean all these things won’t happen or can’t be done? Not at all. Your writing may be so utterly, mind-bogglingly spectacular that no one notices the abundant typos. The structure could be so rock-hard the reader will forgive and forget those atrociously dull opening pages. It’s even possible the idea is so fiendishly, unbelievably clever that nobody will pick up on the fact that every character is a paper-thin cut out carbon-copied from the cast of Heroes (not first season Heroes, mind you… I’m talking about fourth season Heroes)

However, here’s the one thing you can absolutely count on. The moment we notice that Jason Voorhees is now dressed in the colors of Hamas, see that Camp Crystal Lake has been bought out by a wealthy Hassidic group as a spiritual retreat, and read all this through a forest of misspellings and misused words… oh, at that moment we’re all going to groan. Our collective eyes will roll and the thought will cross all our minds—Dear God, I should probably just give up on this right now.

That’s what you’re fighting against when you want to be the exception to the rule. Your audience. They’ve seen attempts to break the rules again and again and again, and the overwhelming majority of these attempts have been simply awful. Remember, the exceptions are rare. Very rare. So when you veer away from the rules, everyone is going to go with the numbers and assume your work is simply awful, too.

In which case, it’s only throwing gas on the fire if you just swaggered in, tossed down your manuscript, and announced it to be a work of staggering genius. Those two things combined will pretty much guarantee your manuscript goes in the large pile on the left, regardless of how good your writing may get around page thirty or so.

A nice, simple rule of thumb. If at any single point you find yourself questioning if something matters—assume it does. Does my main character need to be developed more than this paragraph? Will a reader care that I misspelled forty or fifty words? Do I need to make that part of the story clearer? Should I bother to look up the exact format rules for this?

Your default answer for all of these questions needs to be yes.

Again, this doesn’t mean it can’t be done, and there’s always that chance someone might sit through Friday the 13th Part XII: Dredel of Death and walk out saying “Wow… you know, I never looked at the Middle East in those terms before. It’s so clear now how foolish we’ve all been.” I mean, forget Oscars, we’re talking about a Nobel Peace Prize for Jason this time around. It’s hard for established writers to pull off that sort of thing, though, so aspirants really need to be aware of the very, very steep climb ahead of them if they go in thinking the standards don’t apply to them.

You shouldn’t be scared to do something new, because if you break the rules—break them well, mind you—you’ll get noticed and rewarded for it.

Just remember that a lot of people break the rules because they don’t know what they’re doing… and you don’t want to get lumped in with them.

Next week, we’ll discuss the fact that not all explosions are exciting, and a great deal of drama is not dramatic.

Until then, go write.

November 11, 2008 / 2 Comments

Maybe We Can Fix It In Post…

So, last week I gave a rant that was mostly designed for the novelists and short story writers who regularly look here (all three of them). This week I thought I’d put something out for all the would-be screenwriters who’ve become loyal followers of this blog (both of you).

The rest of you… I have no idea why you keep coming here.

Over the past few months I read scripts for three different screenwriting contests. Two of them are fairly well known. I’m not sure of the exact number, but I probably read well over 200 screenplays in that time period, and I was just helping out part-time.

Seeing this many scripts is, in some ways, a wonderful learning experience. Not only did I get to see the same mistakes made again and again and again (thus reinforcing the fact that I will never commit the same mistake) but I also got to see the entire review process through the eyes of a reader and share my thoughts with other people on this side of the line.

That being said, two important things to remember as I go into this list…

First, readers are human. They generally have to read about a dozen scripts every day (The Stand by Stephen King has fewer pages than a single day’s worth of feature scripts), and they’re usually only making fair to average pay doing it. They get frustrated, they get bored, and they will make snap judgments even when they’re trying to be as fair and impartial as possible. Every time you make it easier for them to render that judgment—one way or the other—you’re doing them a favor.

Second, reading scripts is not about mining for gold, it’s a weeding-out process. For most readers, the job is not to find the best of the best, but to clean away the worst, the barely-adequate, and the mediocre for the higher-paid people above them.

As an additional side note, I’ve determined a simple truth I call the 50% rule. It holds for screenplay contests, and I bet it also counts for anthologies, job applications, and blind dates.

If you take any body of submissions, about half of them will have no business whatsoever being there in that group. These are the submissions where the reader knows by page two there’s no point in turning another page. Maybe it’s because they submitted a western to a sci-fi contest, or vice-versa. Perhaps there’s a 120 page cap and it’s a 200 page screenplay. It could even be handwritten in crayon. One way or another, when you look at the odds for a contest, remember that half those people aren’t even going to be your competition. Or, awful as it may sound, you won’t even be theirs.

Here’s ten of the most common reasons why.

Typos

Yeah, can you believe I’m harping on this again? When I first wrote the “Contest Beat” column for Creative Screenwriting (recently resurrected as “Eyes on the Prize”) I interviewed dozens of contest directors and asked each of them what were some tips for aspiring entrants. Across the board, the answer that every one of them gave was spelling and grammar.

Now, a random typo is not going to sink your chances. We all make mistakes, and readers know that, too. If I’m going through your script and there’s a typo on every page, though… Heck, there were a few screenplays I looked at where I wasn’t even thirty pages in and I’d lost track of how many there were.

Whenever you hand off a manuscript you’re trying to convince the reader that you are an advanced writer. You’re ahead of the average Joe or Jane, someone who can do more with words and letters than just sign their name, send a text message, or scribble a shopping list. The absolute, bare-bones basic tools of writing – any writing– are spelling, grammar, and vocabulary. If you aren’t a master of the basics (you, not your word processor’s spellchecker), how can you hope to do anything advanced?

Apostrophe S

You could argue this goes under typos, but to be honest it’s in a class by itself. Messing up an apostrophe S will stand out on the page like a flare. There is no worse mistake you can make. Seriously. None. As I said above, we all make mistakes now and then, but it’s obvious when a writer’s just throwing down random apostrophes and getting a few right by sheer chance.

Knowing the difference between a plural, a possessive, and a contraction is past basic—it’s a fundamental part of the English language. Stop writing, go get some grammar books like Eats Shoots & Leaves or even just the MLA Handbook and actually read them. Promise yourself, as of this moment, no more guessing or taking wild stabs in the dark. A real writer has to know how apostrophe S works.

Excess Title Info

You would be stunned how many scripts were submitted to these contests with things like MY TITLE—crap draft right on the first page. One didn’t even use the crap, but a more vernacular form. No, I’m serious. Sometimes they’re in the file name with electronic submissions, which is also a bad time to see MY TITLE—(other contest’s name) Submission. Even just plain old MY TITLE—1st draft. Only your first draft? And you thought it was ready for a contest? Well, okay… I guess that’s better than the script that was copyrighted back in 2001 and probably hasn’t been changed since…

Don’t give a reader any reason to prejudge your script. Strip off any and all draft numbers or extraneous comments to yourself before you send it out. I’ve got over a dozen screenplays to read today, and honestly, if you’re going to hand yours off and tell me it’s crap right up front… well, you’re saving me some time, thanks.

The script is about a writer

Seriously, you would not believe the percentage of scripts that are about novelists or wanna-be screenwriters. Out of 150 scripts I read for one contest, nineteen of them had writers as a main character. That’s almost one out of every seven–over 14% of them! They were all awful and not one of them advanced.

Not to sound harsh, but no one cares about the day-to-day struggles you go through as a writer. Trust me, I do it for a living, I know. They also don’t care about the day-to-day struggles of a thinly-fictionalized version of yourself. And they also don’t care about the sheer joy of the creative process, the way impossibly beautiful women and handsome men are drawn to creative types, or the wild, quirky, and outgoing nature every writer has.

And for God’s sake, it’s the worst ending in the world when the writer-character finally sells their book or screenplay, everything is now wonderful and perfect in the world, and they win the Pulitzer/ Oscar/ whatever…

The story never addresses things

It’s okay to have mystery in your story. It’s okay not to reveal everything. Heck, it’s even okay to have wild, absurd coincidences. Many movies and shows have had success by not fully explaining who that cigarette-smoking man is, why that girl down in the well is so evil, or what the heck is going on on that damned tropical island. We all like this sort of stuff, and when it’s done well it what makes your story the one people talk about and remember for ages.

However, these things still need to be acknowledged. A story can’t just get away with “it’s a secret” and expect that readers (and an audience) will just accept it. A reader can see the difference between a real mystery and a bunch of awkwardly-withheld information. It’s also apparent when a writer is keeping a secret and when they’re just trying to be mysterious because… well, people like mysterious stuff.

You can get away with a lot of bizarre stuff if your characters at least acknowledge the mystery or absurdity of it. On the show LOST we found out that someone on the plane was travelling with a pregnancy test. Yet before the audience even had a chance to mock this little bit of deus ex machina, one of the characters did. “Who travels with a pregnancy test?” laughed Kate, trying to calm her friend Sun. And with that, this ridiculous coincidence was addressed and allowed. A few years back in an issue of The Incredible Hulk, writer Peter David had sidekick Rick Jones saved from an exploding Skrull warship because he always wore a mini-parachute under his clothes in case he had to escape from an exploding Skrull warship. When Bruce Banner pointed out how absurd that was, Rick looked up at the sprawling cloud in the sky and said “ What do you mean? I needed it, didn’t I?”

Again, there’s nothing wrong with mystery and coincidence. Just make sure it really is a mystery, not just an attempt to look like one.

Crowd scenes

I read one script that introduced twelve characters in the first ten pages, plus a handful of minor ones. The record was seventeen in the first five pages. As I recently explained to a friend of mine, this is like pouring out a truckload of gravel and asking someone to take note of what color stones they see.

Pace the introduction of characters. If you tell me ten people walk into a room, you don’t need to give me all their names, genders, physical descriptions, and character quirks all at once. We can get to know them as the situation arises.

Confusing names

This may sound a little foolish and obvious, but if your story has characters named Paul, Paula, Paulina, and Paola (and one short I read did) it’s going to be very, very difficult for a reader to keep track of who’s who. Confusing as all hell, to be honest. I mention it because I saw a double-handful of scripts that all suffered from this problem and it was one of the factors that kept most of them from making it to the next level of the competition. If you look at many published novels, you’ll see it’s actually rare to get multiple characters whose names start with the same letter—it just makes for an easy mnemonic. You’re more likely to see Andrew, Bob, Cedric, and Dave than to see Andrew, Angus, Bob, and Bill. The Matrix had Neo, Morpheus, Smith, Trinity, and Cypher. Casablanca has Rick, Elsa, Victor, Louis, and Sam. Raiders of the Lost Ark had Indy, Marion, Belloq, Sallah, and Toht. Even with the huge squad of Colonial Marines in Aliens, the only double-up is Hicks and Hudson.

On a somewhat similar note, if you have a wedding planner named Leslie who’s male, make sure it’s plain and obvious he’s a man. Likewise, if your grease-covered auto mechanic Charlie is a woman, it needs to be clear up front she’s a woman, with no ambiguity at all. Nothing frustrates readers more than to get ten pages in and realize they’ve mentally assigned the wrong gender to a character, because it means they have to go back over everything they just read. So be careful with names like Pat, Chris, Sam, and so on.

Nothing ever happens

Most professional script readers will give you to page ten and then stop reading if they’re not gripped by your words. If your writing in and of itself is phenomenal, they might go along with you until page twenty or so. However by page twenty if there isn’t a definite, solid story happening, your script ends up in the large pile on the left. One script page is roughly one minute of screen time (a little less, actually), so try to find a movie where at least the basic story hasn’t been set out for the audience by twenty minutes in.

If your story (your real story) hasn’t begun by page twenty, look back over your script and see what is happening in those pages. Is it vitally important to the character? Is it advancing the story? If not, you may want to trim it out, or perhaps move it to a later scene.

Pointless changes

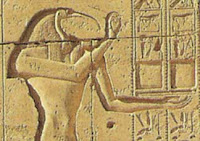

A common storytelling device is to take a known story (either fictional or historical) and change an element to put a new spin on it. Disney used to do this quite often with their animated versions of stories like Robin Hood. Another way to look at this is the “What if…” method of storytelling. What if aliens did build the Egyptian pyramids? What if a time traveler killed Kennedy? What if someone won the lottery?

The catch here, of course, is that such a change implies other elements of your story would change. If your team of agents find evidence Kennedy was killed by a time traveler and then continue to deal with the OPEC crisis… what was the point? Why bother to have your main character win the lottery if winning it doesn’t change a single thing in their life?

If you’re going to have a major tweak like this in your story, there should be a reason for it. If you’ve decided to tell the history of the Maya with cgi geckoes acting out all the parts… it should be apparent why.

Short brads

Yeah, this is stupid and it really shouldn’t have anything to do with how your script is received… and yet…

Few things are more frustrating than having a script constantly fall apart while you’re trying to read it. You turn the page, the brads bend, and suddenly you’re holding a pile of fanning papers. And the last thing you want is for a reader to be going through your screenplay and feel constantly frustrated.

If you’re alredy investing forty or fifty bucks to enter a contest, go the extra few feet and get the right size brass brads. You want the big, beefy ones that are over an inch and a half long– enough to go through 120 sheets of paper and have plenty left over to bend back.

There they are. Ten things that crop up again and again, most of which will guarantee you a place in that large, left-hand pile.

So go look at your writing, and make sure that doesn’t happen to you.