Category: ideas

September 27, 2012

Fleshing Things Out

February 17, 2012 / 10 Comments

I Long For a Bungalow…

Long overdue pop culture reference.

Birdhouses are pretty basic things. Four sides, floor, perhaps a two-sided roof if you get fancy. They generally have one entrance and not many features past that little peg for the birds use to land on or launch from. I think I built two at different points in my childhood. Although I think one was made out of a plastic milk jug, so it doesn’t count for our purposes today.

Birdhouses are pretty basic things. Four sides, floor, perhaps a two-sided roof if you get fancy. They generally have one entrance and not many features past that little peg for the birds use to land on or launch from. I think I built two at different points in my childhood. Although I think one was made out of a plastic milk jug, so it doesn’t count for our purposes today.August 4, 2011 / 4 Comments

Simpsons Did It!

A pop culture reference that’s so spot-on it’s not even funny.

Okay, it’s a little funny…

(General Disarray, go get the minions before they get lost…)

One of the big worries with creativity is wondering if you really are being creative. Is that clever new idea of yours something you came up with all on your own, or is it something you unwittingly borrowed from someone else? Maybe you skimmed over the back copy of a paperback in your local neighborhood bookstore or read a few spoiler-filled reviews on Amazon and your brain just filed it away. Worse yet, what if your clever story gets out there and then you discover five other people already had similar ideas. Now you just look like some hack plagiarist.

I’ve been involved in a bunch of discussions about stuff like this in the past few weeks. Has anyone crossed X with Y before? Have you ever seen this element used in that genre? What about that plot but in this setting?

The answer to all of these, alas, is yes.

Some guru-types like to drawl on about how there are only seven stories (or nine, or thirteen, depending on who’s selling what this week). While I think this is an oversimplification, it does point out an obvious truth. Most stories have things in common with other stories. That’s just the way of it. The same type of characters show up. The same situations arise. The same relationships form.

Here’s a random observation for you. When was the last time you met someone who didn’t remind you of someone else? Think about it for a minute. When we were little everything was new and fresh but as we got older we started to see patterns and similarities. A guy I met at a birthday party last weekend reminded me of a guy who lived across the hall from me in college. When I first met her, I thought my girlfriend looked a lot like one of my next-door neighbors. A production assistant I used to work with looks kind of like a sound mixer I know in San Diego. Another one reminded me of my cousin Chrissie crossed with a bit of Angelina Jolie (a very good mix, I have to say).

But those are all first impressions. As I delve deeper, I start to see the uniqueness of each person. The better I got to know them, the more Leo, Colleen, Russ, and Sarah became individuals and those superficial similarities dropped away.

Still, those initial generalities can be a bit bothersome. If there’s something else out there that’s similar to your work, should you worry about it?

Probably not.

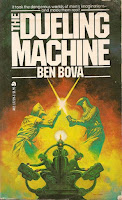

Submitted for your approval is The Dueling Machine. It’s a 1969 sci-fi novel by multiple-Hugo-award winner Ben Bova. In the far, far future, a brilliant scientist has created a machine to help reduce hostility. It’s “a combination of electroencephalograph and autocomputer” which lets two or more people connect their minds through the machine and interact in an imaginary dream world that they create inside the machine. The story comes about when someone is killed during one of these “simulated” duels—is it possible that dying in the imaginary world could make someone die in the real world?

Hopefully this premise sounds a bit familiar to you. It should because it’s a big chunk of the plot to The Matrix movies. And The 13th Floor. Also the Lawnmower Man films. Plus there’s a few books like Cybernetic Samurai and Snow Crash and Giant’s Star. And that television show VR5 that was on for a while. And about a hundred Star Trek episodes where people get trapped on the now-deadly holodeck, because the holodeck safety systems are apparently made of cobwebs and wet tissue paper. Heck, you’ve all probably got a dozen more at your fingertips, don’t you?

For the record, there are also dozens of books and movies and television shows featuring vampires in space (one’s actually called The Space Vampires—it was the basis for the movie LifeForce). And zombies in the old west. And new takes on time travel, space travel, politics, Jekyll and Hyde, all that stuff.

Now, this doesn’t mean that most stories copy other stories. We all draw from a lot of the same sources, so our thoughts are going to follow a lot of the same paths. But even on those paths we’re all going to march to the beat of our own drummer, so to speak. We’re also going to dress differently, bring different things with us, ask different people to come along, and we’re all probably heading down that given path for different reasons.

Y’see, Timmy, we put our own stamp on everything we do. If I did a modern version of Dracula and you did a modern version of Dracula, neither of us would end up writing Salem’s Lot, which was Stephen King’s modern version of Dracula. You might stick with Europe, but I’m probably going to set mine in southern California. We’d have our own ideas and notions and way of looking at it, just like Mr. King did.

Now, there’s a downside to this apprehension, too, and it’s kind of similar to the people who won’t write anything because they’re too busy learning how to write. Sometimes we—yes we—get so caught up in worrying if something is original that we grind to a halt trying to prove it isn’t. This desperate need to avoid being a copycat brings things to a dead halt.

True story —I was working on a book a few years back (right before I was inspired to start Ex-Heroes, in fact) called Mouth. As I was typing away, I suddenly came up with the coolest way to explain teleportation ever. I mean, this was Stephen Hawking-level brilliant. It was, if you’ll pardon the phrase, sheer elegance in its simplicity. I typed up a quick scene where Character A explained it this way to Character B, read through it, and realized it was even cleverer than that.

Too clever, in fact, for a guy like me to come up with it. It was too clean. Too perfect.

In a panic, I wracked my brain trying to figure out where I’d heard it before. Because I must’ve seen this somewhere. Online? In a comic book? All I was reading at the time was Amazing Spider-Man and that was all packed full of “Civil War” nonsense. Maybe a television show? What had we gotten from Netflix in the past few months?

I asked my girlfriend to read it. I figured she might recall whatever this source was, because I kept drawing a blank. She went through the chapter, got to the questionable explanation, and loved it. When I asked her where she’d seen it before, she couldn’t remember ever seeing it. After I pressed her for a bit and she re-read it again, she admitted it was vaguely like the explanation of “tessering” in Madeline L’Engle’s classic A Wrinkle In Time, but only in that it took what was plainly a very complex idea and boiled it down to an extremely simple explanation.

In other words, it was all mine. But I wasted a week worrying over whether or not I’d copied it.

Do a quick look at your chosen field. Make sure no one’s done something exactly like your idea. Then just write. Your own style and vocabulary and characters will give it a flavor all its own.

Like the Buddha says, don’t sweat the small stuff.

Next time, if I don’t get any suggestions, I may have to fall back on spelling.

Until then, like I just said, go write.

June 17, 2011 / 4 Comments

Jane, You Ignorant Slut!

Pop culture. Really. I pity you if you don’t get it.

Anyway…

I know I said I was going to write about mystery tips, but I got distracted by a few things. And then my mind went other places. So I ended up scribbling notes for some potential rants down the road rather than working on the one for… well, this week.

So I thought, hey, what if rather than doing a rant about mysteries, I did one about getting distracted by other ideas? Yeah, it’s more of the procedural end of writing than I usually deal with, but isn’t it about time to try something new? Doing something a little different could really ignite the old spark again, right?

Well, let’s see…

A while back my girlfriend told me a wonderful story about the slutty new idea. I laughed a lot and immediately identified with it. She’d read it on a message board, but couldn’t remember who posted it. I dug around and found it here on Richard F. Spencer’s blog, and he’ll be getting credit from me unless I hear otherwise.

The story goes something like this…

You, the writer, are out with your story. Maybe it’s a novel or a screenplay or just a short story you’re working on. Whichever it is, you’ve been together a while and you’ve fallen into a good pattern.

Perhaps, in fact, too good. Maybe a bit of a rut. You just don’t have the enthusiasm for the story you once did. There was a point that it was fun and exciting and all you could think of, but as of late… well, the honeymoon’s over and now it actually takes a bit of work to get anywhere with your story. Things have almost become mechanical.

So, anyway, you and the story are out and you happen to notice an idea across the room. It’s big and bright and it’s got that look to it that just says “you know it’d be fun to tumble around with me for a while.” It’s got a naughty edge to it, and it’s showing just enough to make you think about all the stuff you aren’t seeing, and how great it would be to get at those hidden parts. Just looking at it across the room you know that is the kind of smoking hot idea a writer’s supposed to have, not the dull thing you’ve somehow wound up with

In fact, let’s just take a moment and be honest with ourselves. That’s how we all want things to be with our ideas, right? It’s supposed to be a wild and spontaneous and intoxicating relationship you just can’t get enough of. You want it to keep you up late and wake you up early so you can get right back at it.

By the way, any innuendo or double meanings here are purely your own inference, I assure you.

Alas, more that a few of us know the awful truth of the slutty idea. Oh, it’s fun at first, but then one of two things happens. Sometimes you find out there’s not really anything else to it. Oh, that first night is fantastic, maybe the week after it is pretty cool, but it doesn’t take long to realize the slutty idea is… well, it’s a bit shallow. You had some fun, but after a couple days you realize things just aren’t going any further.

On the other hand, things might work out with you and the idea. The passion fades a little bit, but you’re still giving it your all and getting quite a bit in return. Eventually the two of you settle down into a comfortable story together. And just as you realize things are becoming a bit of work with your story, the two of you are sitting down one evening and you happen to notice a slutty new idea hanging out over at the bar…

Again, let’s be honest. We’ve all been there.

Now, a sad corollary to this that I’ve developed is the booty call idea. This is the idea you used to spend a lot of time with, but now you don’t for one reason or another. Maybe you needed some time apart. Maybe it just wasn’t working out between you. It’s possible you decided to call it quits altogether.

But, there you are late at night, and suddenly that idea looks really sweet again. There’s a lot of stuff you could do with that idea if you had a little time. Nothing serious, mind you, just a writer and an idea hooking up for a few hours and doing what they do. Yeah, there’s other things you should be working on—putting serious effort into, really—but one night won’t make any difference, right? Heck, not even the whole night. Just a couple hours to ease back into it and take care of that little itch you’ve had.

And yeah, maybe this time it’ll be different. But more often than not, come morning you’ll feel a bit guilty about that time you spent with the booty call idea when you should’ve been, well, doing other things.

Y’see, it all comes down to focus. Writing isn’t always going to be fun and fast and exciting. Sometimes it’s going to be work. There are going to be periods when the days just blend together. But if you stick with it and don’t just chase after every little idea that flashes you a bit of plot, you’ll find that most of the days are going to be good ones. And more than a few will be fantastic.

So, don’t chase after the slutty idea. Resist the urge to check in with the booty call idea. You’ll be a better writer if you do.

Speaking of which, I should really go work on that top ten mystery rant so I’ll have it for next week.

Until then, go write.