You’ll have to excuse me for running a bit late. My old laptop came to an unexpected end on Monday night and I lost the first draft of this post. Believe me, it was far more witty and insightful than what you’re about to read.

That being said…

As the story goes, there once was a young carpenter here in Hollywood

“I thought the point was you were supposed to think he was a grocery clerk,” said the frustrated actor.

And that young bellboy grew up to be Harrison Ford.

Who, let’s all be glad, also had enough sense to stop making Indiana Jones movies after Last Crusade.

(la la la la la la la la not listening la la la la la la la)

Anyway…

This fun observation by Mr. Ford hammers home a problem I’ve seen with a few narratives. It’s not uncommon for fledgling writers to center the narrative around a character and then tell a story that’s far beyond the scope of said character. nailing down the perspective a story is being told from is tough, and picking the wrong one can leave the story painted into one corner after another. This comes up most often in two forms—a first person person story and an epistolary story.

To recap…

In a first person story the reader gets everything through the eyes and thoughts of one of the characters. On the plus side, we get to know and see everything this character knows and sees. On the down side, we only get to know and see what this character knows and sees. First person is a very limited viewpoint. We don’t get the suspense of us knowing something’s happening that the character doesn’t know about. This also means we can’t be privy to extra detail, nor can we have any doubt if something did or didn’t register with the main character. To Kill A Mockingbird is a phenomenal first person novel, as are Moby Dick, A Princess of Mars, and Stephen King’s novella “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption.”

(Yeah, there’s no the in the original title. Seriously. Check it out.)

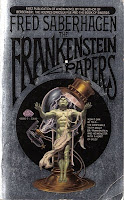

An epistolary novel is told through “existing” documents. As the name implies, it was originally letters, but it can also include journals, police reports, newspaper articles, and even blogs or tweets or social network updates. By its nature, a lot of epistolary writing comes across as first person, but there’s a notable difference. This form is very episodic. There are gaps in it where the “writer(s)” didn’t have time or inclination to put things down on paper. Dracula is an epistolary novel, as is Fred Saberhagen’s The Frankenstein Papers, and Mr. King did a rather horrific epistolary short story some of you may remember called “Survivor Type.”

Now the catch for both of these forms is that once a writer chooses to use them, they’ve just put themselves into what can be a very limiting viewpoint. If Wakko’s my main character, I can’t see, hear, or understand anything if he doesn’t. His limitations are mine. If he doesn’t know what happened out on Highway 10 that night, I don’t get to know.

More to the point, it’s going to make Wakko crumble as a character if he’s constantly stepping out of his boundaries. When he does know what happened out on Highway 10, as a reader I end up puzzling over how and when he found that out. If he suddenly reveals on page 120 that he studied Goju-ryu karate in Okinawa for twenty years, I’m going to wonder why this never came up before. Since I’m inside his consciousness, inconsistencies stand out like flares and each one means I’m going to believe in him less and less.

I recently read a book where the narrator goes to great lengths to tell us she has no writing ability. Oh, like anyone who graduated high school she knows the bare mechanics of how to write, but she’s not at that level that she’d consider herself a writer. Why, not counting work memos, this is probably the longest document she’s ever committed to paper (or computer memory). So hopefully we, the readers, will go easy on her as she tries to record the events of the past few days.

Said narrator then launches into a flourish of vivid metaphors, purple prose, elaborate sentence structure, and parallel constructions. This went on for the entire book. The vocabulary was the kind of stuff you might hear tossed around by Harvard alumns trying to outdo each other at literary conferences.

She did not come across as someone who never expressed themselves through writing.

Definitely didn’t sound like a grocery clerk.

Just as a quick note—some writers have managed to pull off stories where a first person character who should be ignorant of certain facts manages to convey enough information for the audience to understand what’s really going on. Perhaps he or she has some knowledge that goes against the character we’ve seen so far. We’ve all seen stuff like this. The illiterate guy who manages to describe a stop sign, the Neanderthal girl who explains a pistol, or the bellboy who it turns out has a degree in chemical engineering so he can help thwart a terrorist attack. You can get away with this once or twice, but it’s a device that wears thin fast so you shouldn’t be depending on it for an entire book.

Now, there’s a somewhat-related problem that tends to crop up in epistolary work. Some writers litter the journals and letters there creating with typos and misused words. The idea here is this makes the documents (and thus, the characters behind them) seem more real because they contain the kind of errors that real people make, especially folks who aren’t usually writing for an audience. And, let’s face it, it also spares those writers from learning how to spell or bothering to do any sort of editing.

The catch here is that any typo is going to knock a reader out of the story. It’s going to be an even bigger hit if the reader stops to figure out if this was a deliberate mistake or just… well, a mistake. Like up above when I used there when it should’ve been they’re. All of you stumbled on it, and a few of you probably stumbled even more as you paused to figure it out if, being the sneaky bastard I am, I was doing it for a deliberate effect. And I was. And you still stumbled and paused.

A great example of doing this correctly is the book Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes. It’s the epistolary story of a man named Charlie who’s mentally challenged. If you felt cruel, you could call him severely retarded. The book, in theory, is a journal his doctors have asked him to start writing. It’s painful to read. Charlie can barely spell, has only the barest understanding of grammar, and no real idea how to express himself.

His doctors are giving him a series of treatments and surgeries, though, and as the book progresses the journal entries become clearer and more elaborate. At one point they actually get close to going the other way—Charlie has become so smart he’s taken over the enhanced intelligence project and is using his journal for research notes and brainstorming. Now the journal’s almost unreadable because it’s so advanced! The language he uses becomes one of the elements Keyes uses to show the reader how much Charlie is changing.

So one of the big tricks with these two formats is to create a character who’s believable and relatable, but still has the abilities, intelligence, and experience to deal with whatever challenges the plot may throw at them. A cheerleader may be great for figuring out who ruined homecoming, but not as much for an assassination plot. A Nobel-prize winning physicist isn’t going to be much help at harvest time. The trans-warp drive on a starship is probably going to be out of the range of the guys who work at Jiffy Lube.

Choose your character wisely.

Next time, I was going to blather on about the world we live in. Or, at least, the one we thought we were living in.

Until then, go write.