There’s a little maxim you may have heard– work smarter, not harder. If you haven’t, what it means is some folks solution to every problem is to throw 100% of their effort at it. They’d throw 110% at if that was possible. But it’s not.

Meanwhile, another type of person will look at the problem and figure out how much effort it actually needs. Do we want to do the time and work to dig through the mountain when we could go over it? Or around it? And then we can save all that effort and energy for somewhere we actually need it rather than burning out early on problems we could’ve just, well, easily gone around.

I mention that so I can tell you a few stories. There’s a theme. Trust me.

A bunch of you know I worked in the film industry for about fifteen years. Mostly television, some movies. Some of it’s even stuff you’ve heard of.

An all-too common problem I saw from beginning directors (and let’s be honest– also from plain bad directors) was an urge to make every single shot special. Every one had to be Oscar or Emmy-worthy. Didn’t matter if it was a wide shot, a close-up, a master, or coverage. Didn’t matter where it fell in the story. Didn’t matter what the day’s schedule looked like. Every shot of every scene required hours of set up and rehearsals and discussions and little tweaks and adjustments.

Now, on one level, yeah, this is sort of the director’s job. To make it all look good. But there’s a lot of nuance there. I can make an individual shot look good, sure. But does it fit with the last good shot? Does it fit with the rest of the scene? Is the editor going to be able to cut these shots together in a way that works within the filmic, visual language we all know on some level? Heck, does it even fit in the story I’m telling?

Plus, well… this is going to be an awful shock for some of you, but there are a few capitalist aspects to filmmaking. Yeah, sorry you had to find out this way. Making a movie costs money. It has a budget, and one way that budget’s expressed is in how long you have to shoot something. Spielberg can take a week waiting for the absolute perfect sunset his heroes can ride off into, but I’ve got today and it took us too long to get to this location so I might get two tries at this if I’m lucky and that’s it.

Anyway, what this amounted to was we’d get stuck with a new (or bad) director and they’d spend hours on the first two or three shots of the day. Like I mentioned above, it didn’t matter what they were or were they fell in the story. These folks would spend the whole morning working on whatever scene happened to be first up, and then we’d come back from lunch and surprise we still have 83% of today’s schedule to shoot in the last six hours of the day. So we’d rush through all that stuff—again, no matter what it was—and then come in the next day and, well, usually watch them do the whole routine again.

And this was really bad, from a storytelling point of view. The final film or TV episode would end up uneven because there was all this visual emphasis on random scenes that didn’t need it and often very little on scenes that did. Heck, once or twice I saw folks spend all this time on a random “pretty” shot and it wouldn’t even get used because there was no way to cut it in. These directors were so focused on making individual shots look amazing—no matter what that particular shot was—that they didn’t stop to think of the film as a whole.

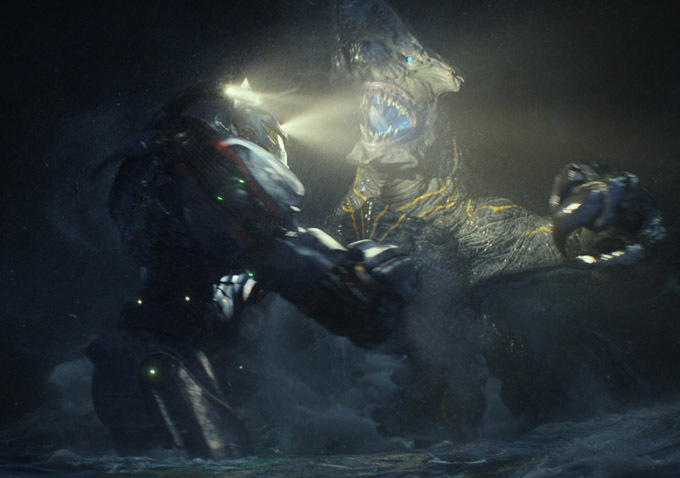

Okay, this actually reminds me of another fun story (still semi-related). A few years after I got out of the industry, my beloved took me to an Academy screening of Pacific Rim (yeah, she’s super cool) where Guillermo del Toro was there to talk about the movie. One of the things he stressed was even though he knew large swaths of the movie were going to be mostly computer-generated, he didn’t want any sort of wild, impossible “camera moves.” You know, the ones where the camera’s essentially whizzing through the air and then it loops down under the monster’s armpit to come back up between punches from the giant robot and then it circles around the two of them before pulling back for the panoramic shot of the city in flames as they fight? We’ve all seen some of those, right?

Yeah, del Toro didn’t want any of that in Pacific Rim. He understood those sort of visuals becomes distracting very easily, and once the audience is thinking about them they realize how impossible these moves are. And suddenly a big chunk gets lopped off their willing suspension of disbelief. They become consciously aware they’re just watching a movie rather than getting drawn into the story. That’s why the CGI camera shots in Pacific Rim are all set up as if actual, physical cameras are there doing regular, normal shots.

Now… I told you all this so I could tell you about Krishna Rao.

I worked with Krishna on a show called The Chronicle, back when the SyFy Channel was called the Sci-Fi Channel. Krishna started out in the crew (one of his very first film credits is on John Carpenter’s Halloween) and over the years worked his way up the ladder (seriously check out his list of credits), becoming a director of photography and quite often a director as well. Which is how I knew him. He had a loose rule he tended to follow when he was filming an episode. Honestly, I’m not sure he ever even put it into words, because it didn’t really click in for me until the second or third time I worked with him.

Krishna would only really plan on one pretty shot a day. That’s it. Once a day we’d have a complicated move with the camera dolly or some other elaborate shot that required lots of set-up and rehearsal. Everything else would be simpler, workhorse stuff– masters, overs, some coverage if it was needed. And I’m sure a few folks reading that may have some thoughts about “real” directors or the lack of art in American television or whatever. But here’s a few things to keep in mind.

Krishna made his schedule pretty much every day. Because he didn’t overload himself trying to do too much, he could make sure all his material fit together just how he wanted. He still had at least seven solid, very pretty shots per episode—that’s a cool shot every six minutes in a standard 42 minute television episode. And because he was being careful about using them, they always landed where they’d have the most visual impact.

And, sure, like any rule, sometimes he’d bend it a bit. He wasn’t against doing something fun or clever if he could do it quick. Sometimes we’d do two pretty shots in a day, maybe because of stunts or special effects. But these were always the exception, not the rule.

And his episodes always looked fantastic,

Okay, all interesting, but what does it have to do with books? With, y’know, our kind of storytelling? We don’t deal with visuals.

Y’see Timmy, something I’ve talked about a few times here on the rant writing blog is pointless complexity. In structure. In dialogue. In vocabulary choices. I’ve seen stories with the most confusing non-linear structure just because the writer… felt like using non-linear structure. There are folks who scoff at using pedestrian words like blue or house or said. They spend all their time figuring out how to bury their story (or hide the fact that they don’t actually have one) behind layers of complexity.

To be clear, I’m not saying any of this stuff is bad. Personally, I love a story with a clever structure, an author who knows how to use their full vocabulary, and some twisty-turny character motivations. But a key thing is that when they do this—when they make a choice that isn’t the basic, workhorse choice—is that it’s actually making things better. This added complexity is an improvement, not an affectation.

And one other thing to consider. Sometimes… we need the simple stuff. We need the workhorse to just come in and deal with this paragraph or page. Because if I try to make every single sentence/ paragraph/ chapter the one that gets me an award, what I’ve really done is make a flat, monotone manuscript. If every single line is the utterly amazing artistic-piece-of-beauty one, they all have the same weight. Nothing has emphasis. To paraphrase one of great modern philosophers, once everyone is super… no one is.

So think about where you’re putting your effort. And how much of it you’re putting there. And how much you might want somewhere else.

Next time, I may blather on about the Children of Tama. Haven’t talked about them in a while.

Until then, go write.