And I’m going under the general assumption that if you’ve slogged through all this, you’ve got at least a basic grasp of this writing thing and are hoping to go further with it. Perhaps even make a few dollars with it. And if any of you have a specific question or topic you’d like me to prattle on about, let me know.

Category: tips

January 5, 2012 / 4 Comments

Why Are We Here?

And I’m going under the general assumption that if you’ve slogged through all this, you’ve got at least a basic grasp of this writing thing and are hoping to go further with it. Perhaps even make a few dollars with it. And if any of you have a specific question or topic you’d like me to prattle on about, let me know.

November 4, 2011 / 1 Comment

Changing It Up

So, the back and forth thing really hasn’t gelled in my mind, so I’m taking the easy way out and just tossing up a quick tip. A day late.

October 14, 2011 / 4 Comments

God is My Co-Writer

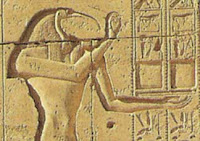

All of which leads to point two. I’m not talking specifically about God in this week’s rant, because a lot of the folks reading this are just as interested in Greek gods, Norse gods, Egyptian gods, Chinese demons, and cosmic entities from beyond time. But when it comes to stories, they all deal with a lot of the same issues.

All of which leads to point two. I’m not talking specifically about God in this week’s rant, because a lot of the folks reading this are just as interested in Greek gods, Norse gods, Egyptian gods, Chinese demons, and cosmic entities from beyond time. But when it comes to stories, they all deal with a lot of the same issues.

Don’t—The simplest thing to do. Is a personal appearance really required for this story to work? The members of Congress have a big effect on my life, but I’ve never seen a single one of them in person. Heck, the only messages I’ve gotten from them have been spam emails and robocalls. But it doesn’t mean they aren’t there influencing aspects of my existence, and it doesn’t mean I wouldn’t be impressed if one of their aides gave me a call to chat about something. Which leads nicely to…

Minions—Gods of any type are impossible to fight, so including them on either side of the story equation really unbalances things. But I believe someone could beat cultists or demons or maybe even an angel. These are the beings my characters should be encountering. Remember, you can almost never get to the CEO because there’s a wall of flunkies, advisors, junior execs, and bodyguards in the way.

Silence is Golden—They used this one way back in It’s A Wonderful Life, when Clarence the angel would have one-sided conversations with the sky. Neil Gaiman did it in both The Sandman and the wonderful Good Omens (with Terry Prachett). Kevin Smith did it in Dogma. Mere mortals can’t hear the voice of God and expect to survive, so the Lord speaks through a number of mediums… or not at all. Keep in mind, to pull this off—especially the one sided conversation—your dialogue needs to be sharp and you can’t fall back on clumsy devices like repeating everything the silent person says just to make it clear what your god hates.

Comedy—People are a lot more willing to accept divine intervention (of one kind or another) if it has a comedy element. If I had to guess, I’d say it’s because when the writer’s not taking the matter seriously, it’s hard for people to have serious complaints. That’s why George Burns and Christopher Moore get away with mocking the man upstairs and The Last Temptation of Christ gets months of picketing. But this tone has to spread through your whole story. You can’t have your deity be the only source of comedy, because then you’re mocking him or her in the bad way.

Minimal Miracles—D’you ever hear the old saying about being so tough you don’t need to fight to prove it? More to the point, have you ever watched a movie where the bad-ass hero just fights and fights and fights and fights and fights? It gets boring, no matter how often he wins. Your omnipotent beings shouldn’t be expressing their power just to prove they can, because that power will start to get boring and take all the challenge out of the story one way or another. If everybody who dies gets brought back to life, what are people even fighting for?

July 21, 2011 / 1 Comment

Tastes Like Chicken

There’s about a hundred jokes in that title. Hopefully one or two of them will fit with this week’s little rant…

Sorry about missing last week, by the way. I’ve been trying to stay ahead on the new project and prepare for Comic-Con, and the blog somehow slipped right past me. Shouldn’t happen again. Well, not for a little while, anyway.

My dad is a phenomenal cook. Have I ever mentioned that? For a guy who refuses to retire and spends his working hours writing up safety protocols, his cooking skills are just fantastic. There was a time when my mother and brother and I were all trying to convince him to open a restaurant, but he wasn’t interested. Cooking was the fun thing he did to relax. He didn’t want to take that extra step and make a job out of it.

We were all fine with it. Mostly because it worked out great for us. My dad can turn Thanksgiving leftovers into a sandwich you’d gladly pay twelve bucks for, so I’m definitely not going to complain. Not as long as I keep getting invited to Thanksgiving.

No, really, this is all relevant. You’ll understand why soon.

As it happens, I’ve had several different friends and acquaintances ask me for writing advice over the past few months. Granted, they all had different skill levels, but none of their questions were really about writing. They were about improving by buying the right books or starting blogs or catching the interest of publishers. I tried to answer as politely as I could, but I’m pretty sure none of them were really listening. I know at least two weren’t.

So, here’s a better way to look at it.

Should you go to cooking school?

I’m sure a lot of you are shaking your heads at that one, but let’s stop and consider it. Cooking is a great metaphor for writing, on a bunch of levels. It’s an art. The end product has to hit certain benchmarks but it also, to a fair degree, is a matter of personal taste. A few rare people have a natural knack for it but most of us need lots of practice. It’s something most of us do every day, but we know only a small percentage of people are good enough at it to deserve recognition or make a living off it.

So, if you want to get better at cooking, should you go to cooking school?

Right up front, let’s be clear. Any cooking school is going to expect that you have a minimum degree of experience and knowledge right off the bat. They’ll assume you can tell flour from sugar on sight and that you know the difference between basil and oregano. The point of cooking school is not to teach you how to make peanut butter sandwiches. If you’re still struggling with these things, cooking school is really a waste of your time and money.

Now, if you plan on making a living off food, cooking school is almost a necessity at some point. Not everyone needs to take classes on desserts and soups and seafood. We’re just never going to use them. There’s about a hundred better, cheaper things we could be doing to improve our cooking skills. There are free recipes online and on the back of most staple ingredients. There are tons of cooking shows and podcasts where we can learn little tips.

And of course, the easiest thing we can do—what hopefully most of you have already seen as the obvious thing I’ve skirted around—is cook stuff. Just get in the kitchen and cook. If I want to be a better cook, the most useful way to spend my time is cooking. Makes sense, yes?

Y’see, Timmy, if you want to be a chef, there’s a point that you need to take some classes, and you’re probably going to keep skimming through cookbooks forever. But it’s all going to come down to spending time in the kitchen. That’s how you become a good cook. Going to Harvard doesn’t automatically make you a great journalist and going to MIT doesn’t guarantee you’ll be a phenomenal engineer. At the end of the day, it all comes down to just doing the work and how hard you’ve been doing it.

Y’see, Timmy, if you want to be a chef, there’s a point that you need to take some classes, and you’re probably going to keep skimming through cookbooks forever. But it’s all going to come down to spending time in the kitchen. That’s how you become a good cook. Going to Harvard doesn’t automatically make you a great journalist and going to MIT doesn’t guarantee you’ll be a phenomenal engineer. At the end of the day, it all comes down to just doing the work and how hard you’ve been doing it.

In fact, there’s a fair argument to be made that cooking school won’t help you become a great chef. It can make you into a good chef, but the greatness comes when you go out and start doing stuff on your own. You don’t hear about Wolfgang Puck or Gordon Ramsay taking classes. Neither of them probably has in over a decade, at least. If you just keep going back to cooking school and never really stepping into the kitchen, it should be clear you’re dooming yourself to a life of mediocrity (at least, on the food-preparation front).

You’ll always learn more by doing the job than you will by reading books about doing the job. Doing the job is almost always more educational than taking classes about doing the job.

So, with all that being said… should you go to cooking school?

A bit clearer now, isn’t it?

This pile of rants is cooking school, in a way. Not one of the great French academies, but a bit higher up than the Home Ec class you might’ve taken in seventh grade (if you’re of a certain age). Probably better than those cookbooks aimed at recent college grads.

A few people who are reading this right now desperately want advice on getting agents and publishers interested, but they haven’t bothered to learn how to spell. They’re convinced they’ll learn some magic structure or word (…mellonballer…) that will make it all easy for them. They’re so desperate to learn the secrets of a good Hollandaise sauce they haven’t bothered to learn how to boil an egg.

I’m guessing most of you can use about half of the various tips and suggestions I throw up every week. There’s weeks that you learn a clever trick or new approach to an issue in your writing. There’s also those weeks you just skim because it’s something you’ve got a good grip on.

And a few of you… well, you’re probably just killing time here, aren’t you? There isn’t much I go over that you don’t already know. You’re just putting off doing some actual work for half an hour or so.

Learn the basics first. Don’t worry about level five before you’ve mastered level one. If you aren’t sure what the basics are, that’s probably a good sign you haven’t mastered them yet. I’m not being glib. If you’re reading this rant with the goal of becoming a better writer, you should already know what it means when someone says “the basics of writing.”

And then, once you’ve hit that level, start thinking about cooking school.

Next time, just for something different, let’s chat about slasher porn and why it’s not as bad as you may think.

(Yeah, I’m probably misleading you a little with that title…)

Until then, go write.