Many thanks for all your patience while I was busy having my teeth drilled out . Hope you enjoyed Thom’s rant last week and he didn’t hurt your feelings too much. No matter how you felt it about, rest assured… you were having more fun.

But enough of my whining…

…whining like a high speed drill on enamel…

This week I said we’d talk about Robocop. The original, not the remake. I haven’t seen the remake yet, so I can’t comment on it. Well, not in a non-nerdy, non-whiny way…

And we said enough whining…

I wanted to talk to you about a common problem that can lead to a lot of issues in a story, no matter what the story is. It doesn’t matter if I’m writing sci-fi (like Robocop), romance, horror, fantasy, or an intense little character piece—this can kill my story. And, in a way, it’s something I’ve talked about here before.

As it happens, this issue’s been summed up by a few people in one simple sentence. These are the eight worst words a writer can hear. There’s no way to put a positive spin on them.

What are these deadly words…?

I don’t care what happens to these people.

You’ve probably heard that old chestnut about the tree falling in the forest. If there’s no one there to hear it, does it still make a sound? Let me ask you this—is Jason Voorhees still scary if no one’s in the forest for him to kill? Is that candlelit dinner on the rooftop still romantic when it’s just sitting there? Are explosions that action-packed if there’s no one running away from them?

I’ve said many, many, many times that my story depends on my characters. A good character has to be relatable, believable, and (on some level) likeable. If my characters are just thin, undeveloped stereotypes, they’re just empty placeholders. If spies are hunting Man #3, it doesn’t mean anything. If I tell you they’re after Bob, it’s a little better, but not much. Once you hear they’re after Jason Bourne, though, now this suddenly means something.

This is the big problem with “starting with action.” That was a storytelling mantra for years. “Start with action—don’t make us wait to be interested.” It didn’t help that some people misunderstood “action” to mean explosions rather than just “something happening”. Thing is, like I was just saying, action is meaningless if I don’t know the stakes and I don’t care about the characters. It might grab me for a moment, but I need someone to latch on to, to identify with, to care about.

Consider this. I’m betting you’ve seen a commercial or headline for the news sometime in the past couple of days. Odds are, with the extent of news coverage and the way it leans toward the sensationalist—you’ve probably seen something along the lines of “five dead in a house fire” or “two killed in shooting” or something like that. Sound familiar? You’ve probably seen at least a dozen variations on this since New Year’s, yes?

How many of these stories stuck with you? Can you name any specifics from any of them? Can you even remember when you saw them?

Odds are, the reason you can’t is because you weren’t connected to them in any way. The news was starting with the events—the action—not with the people. And it bored you.

It’s okay to admit it’s boring. We can all be awful people together.

There is no way I can make a story work if the reader doesn’t care about the characters. None. It doesn’t matter how amazing my futuristic predictions are, how clever my zombie origin is, how fantastic my descriptions are. If there aren’t any fleshed-out characters, it’s just trees falling in the forest.

There is no way I can make a story work if the reader doesn’t care about the characters. None. It doesn’t matter how amazing my futuristic predictions are, how clever my zombie origin is, how fantastic my descriptions are. If there aren’t any fleshed-out characters, it’s just trees falling in the forest.

Now, there are a few exceptions to this, but they’re finesse things.

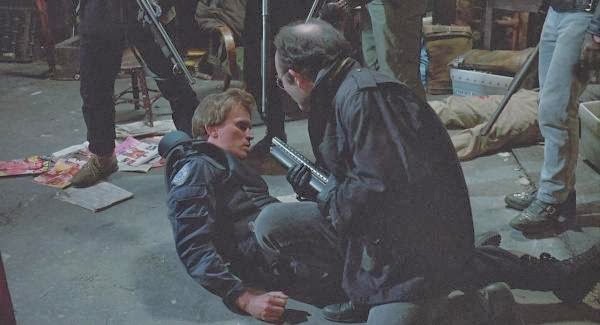

Many years back, I read an interview with Paul Verhoeven about the original Robocop(see, I told you we’d get back to it). The journalist was questioning him about the extreme (at the time) levels of violence in the film—most notably when Murphy is blown apart little by little with shotguns until Clarence Boddiker gets bored and puts a bullet in his head. How could Verhoeven justify this?

It was pretty easy, actually. As the director explained, he only had two scenes with Murphy to establish him as a character before killing him. Not much at all. And while he did good things with these scenes, he realized that the death scene could be used, too, to trick his audience a bit. By giving Murphy a brutal, utterly nightmarish murder—the kind of death any decent person wouldn’t wish on anyone—he immediately built sympathy for him. We don’t know much about Murphy when he dies, but we know he sure as hell didn’t deserve that. It’s the same technique used by a lot of horror stories, especially slashers and torture porn. We might not care about the specific character, but we can identify on a basic human level and know this is an awful thing.

Again, though… it does take a little finesse. I can maybe do this once or twice, tops. After that, my readers are going to be numbed to that shock.

And then they’re not going to care anymore.

So remember to build great characters that your readers care about.

And then do awful things to them.

Next time, speaking of awful words… I wanted to rattle off a few more.

Until then, go write.