No, we’re not talking about tender character moments.

Writers of prose, feel free to take this week off. Or follow along, if you like, and maybe glean a few things here or there.

Would-be screenwriters… let’s talk about that script you’ve been working on. It’s that time of year where a ton of screenwriting contests are beckoning, especially the heavyweights like PAGE and the Nicholl Fellowship.

My friend who blogs over at Live To Write Another Day reads for three or four contests a year, some of which you’ve probably heard of if you dabble in such things. She once told me that easily a quarter of the scripts she’d read for one contest made The Fly II look Oscar-worthy. It ties back to something I’ve mentioned once or thrice here in an off-the-cuff manner. I call it the 50% rule. I’ve got no hard numbers or research backing this up, just my own experience and the experiences of other script readers, editors, and contest directors I’ve spoken to over the years. The 50% rule goes like this…

In any pool of submitted material (contests, publications, etc), half of the submissions can pretty much be instantly disqualified. They’re the people submitting gothic romances to sci-fi anthologies or entering plays in screenwriting contests. They’re also, harsh but true, the incompetent people. The ones who don’t know how to spell, have only the faintest understanding of grammar, and no concept of story structure. The folks who sent in their first draft with all its flat characters and wooden dialogue. If my screenwriting contest gets 1000 entries, I’d bet real money 500 of them can be tossed into the big pile on the left in less than five minutes.

That’s the 50% rule.

Sound unfair? It isn’t. It’s brutally fair, to be honest. Wakko entered the contest to be judged and he was. He made the judgment very easy, in fact. Unless there were a lot of specific promises or assurances past that, he’s got nothing to complain about.

However… I’m going under the assumption you’re not part of that 50%. You’re one of the ones who actually has a chance at this. Not saying a great chance, not saying you’re going to succeed, but you’re good enough at this that you’re not getting discarded in less time then it takes to listen to “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

That being said, there are still traps to fall into and mistakes to make. One of them is submitting a very, very common screenplay that covers well-explored material. I’ve mentioned some of these types of scripts before, so if they sound familiar… well, just try to keep in mind that I thought this was all worth repeating.

I also want to be clear of something else right up front. I’m not saying any of these are bad scripts in and of themselves. Many of them are awesome. I’m sure anyone who follows the ranty blog could easily name half-a-dozen films from the past decade that fit each category. I know I can. But we’re not talking about what’s in theaters–we’re talking about what’s being submitted to a contest. Your competition is not on screen, it’s in the submission pool. That’s a much harder group to stand out in.

So, a few types of scripts you should be a bit leery about submitting. Take a deep breath, and…

The Current Events Script

A friend of mine reading for a contest last year found that a noticeable percentage of the scripts dealt with Israel or Palestine. This was about four months after the brief-lived 2008 war on the Gaza Strip.

If Yakko saw some news report about some fascinating nuance of the world and realized it’d make a fascinating story…here’s the thing. It’s a safe bet at least a thousand other aspiring screenwriters saw the same new story and had the same idea. Even if only half of them do anything with it, and even if only ten percent of those people are sending their script to the same contest as Yakko… that’s still fifty people writing scripts about the exact same thing he is. Even if half of them are completely incompetent and the other half are just barely on par, it means the reader is going to be reading a dozen scripts just like Yakko’s. His script may be the best in the batch, but it’s going to lose a lot of luster because it’s just become a tired, overdone idea. It may be the best take on that tired, overdone idea, but is that really what any of us are aiming to be?

The Formula Rom-Com

The beautiful-but-totally-business-oriented, bitchy female executive who finds love with a middle-class Joe Everyman. The guy engaged to bridezilla who meets the real love of his life. The awkward, nerdy girl who needs to realize she’s the most beautiful girl around. The man chasing his dream girl only to realize his best friend has been his real dream girl all along.

Any of these sound familiar? They do after you’ve read nine or ten of them, believe me. Yeah, flipping the genders doesn’t make them any more original, sorry.

Does the script also have a scene where someone finally ignores their constantly-ringing cell phone in favor of quality time with that special someone? Maybe a prolonged, awkward scene where someone has to change clothes for some reason and ends up in their underwear/ robe/ a towel with that soon-to-be-special someone?

A rom-com has to be really spectacular and really original to impress a reader. In the past three years, I’ve read one that stood out. Just one.

The Game Script

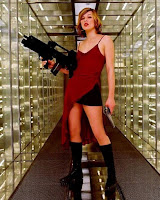

Yes, it was the most amazing night of Dungeons & Dragons or Cities of M’Dhoria or Left 4 Dead in your entire life. That doesn’t mean it’d make a good movie. In fact, odds are it won’t (and I’m not even touching the copyright/ trademark issues). Most of the fairly successful game movies have one thing in common. No, it’s not the hot leading ladies. If you look at Resident Evil or Tomb Raider, they don’t follow the stories being told in their respective games. The screenwriters tossed them out and made up something new that just used a few story or character elements.

Yes, it was the most amazing night of Dungeons & Dragons or Cities of M’Dhoria or Left 4 Dead in your entire life. That doesn’t mean it’d make a good movie. In fact, odds are it won’t (and I’m not even touching the copyright/ trademark issues). Most of the fairly successful game movies have one thing in common. No, it’s not the hot leading ladies. If you look at Resident Evil or Tomb Raider, they don’t follow the stories being told in their respective games. The screenwriters tossed them out and made up something new that just used a few story or character elements.

Y’see, Timmy, most games use a different type of storytelling, one that deliberate makes the audience (i.e. the player) part of the story. Odd as it sounds, it depends on the same problems that make first person so challenging to write. RP games of all types–both the computer and the pen-and-paper ones– want you to project into the story. They want you to fill in the details. This was a cool fight because it happened to Wakko, it was a clever puzzle because he solved it, and it was eerie and atmospheric as hell because he invested in a top-of-the-line surround sound system for his entertainment center. What happened in the story wasn’t cool–what Wakko experienced was.

However, if Wakko can’t get every one of these sensations perfectly on paper–and translate the experience to a believable third person character–it’s just going to be a lot of shooting while flat, uninteresting people run from A to B.

The Character Script

A popular thing in the indie field is the character script, also known in Hollywood (somewhat demeaningly) as “the actor script.” At its heart, it’s a tissue-paper-thin plot with a handful of character sketches thrown into it. Nine people wait for their connecting flight and strike up random conversations. Five people on a road trip have long talks about life. A group of women talk about relationships. A group of men talk about how their lives have gone in unexpected directions.

On one hand, it’s hard to argue against scripts like this. These really are the type of people you’d meet in an airport, and they really are the type of conversations and brief relationships that would spring up. On the flipside though, is there anything challenging–or interesting— about something that’s indistinguishable from the boring, everyday life we all lead?

This leads nicely into…

The Therapy Script

There’s an interesting sub-group of screenplays that seem to have sprung out of some psychology exercise or group coping session. Usually they involve someone telling off their mother. Or their father. Or their abusive boyfriend. Or their cheating husband. Many of these scripts involve female protagonists, but only enough so it’s worth mentioning. The overall feeling of them is you’re reading a story somebody wrote to help them work through some issues. The object wasn’t to tell a story, but to cleanse and purge or something like that.

The big problem with these scripts is there’s rarely anything to them beyond this big moment of therapeutic release. Everything leads up to that, and not much happens after it. That one moment is all the character development and conflict that happens in the script. So, when you boil it down, it’s just a story about someone throwing out their abusive spouse or learning to trust again or yelling at their shrewish mom. And nobody wants to read that. Not even Oprah. Definitely not a contest reader.

The True Script

Closely related to the therapy script is the true script. More often than not, the title page or closing cards reassure the reader this tale is based on real events involving me/ my parents/ my best friend/ someone I read about in a magazine article. These are tales of cancer survival (or not), abused children, Rwandan genocides, military struggles, and various other unsung heroes and villains of this world we live in. Alas, often they’re about struggling writers searching for someone to recognize their genius. The fact this is a true story is often stressed to give a certain validity and gravitas to what the reader is about to take in.

Thing is, no one cares if the story is true or not. Nobody. They just care that it’s a good story and it’s well-told. And in that respect, Dot’s tale of an abused nine-year old cancer survivor in Rwanda needs to stand up against the story of a cyborg ninja battling prehistoric lizard men from the center of the Earth. Whether or not one of them’s a true story is irrelevant. In the end, you are telling a story, and it’s either going to have its own validity or it isn’t. If it’s easier to read, if it has interesting characters, if it has sharp dialogue– these are what determine if a script is any good or not. Reality just doesn’t enter into the equation for the reader, so it can’t for the writer.

It’s worth mentioning that sometimes the true script and the therapy script have a horrific bastard child I call… wait for it… the True Therapy Script. In screenwriting terms, this is like one of the little mutant monster babies from that ’80s horror classic It’s Alive. Did your girlfriend leave you? Write a script about it. Tons of father-issues you’re working through? Write a script! Want to share your touching journey through the hell of addiction to booze, drugs, sex, or whatever? There’s a screenplay in that, for sure!!

Hopefully you all caught the sarcasm in those last few sentences.

The Holiday Script

If you add in movies of the week and straight-to-DVD, there’s a good case to be made that holiday films are one of the best selling genres out there. However, as far as a contest is concerned, the trick is to come up with something the reader hasn’t already seen again and again. They’ve seen Santa Claus quit, get fired, and be replaced a dozen times this month alone. The Easter Bunny has been in therapy, evil spirits have tried to save the bad name of All Hallow’s Eve, Cupid has taught someone the true meaning of love, and the first Thanksgiving story has been told—many, many times and many, many ways.

Just in case you missed it– they’ve been told many times in many ways.

The Writer Script –

I can repeat this one until I’m blue in the face, but I know in my heart it won’t change anything. Do not write scripts about writers. Jennifer Berg, the director of the PAGE Screenwriting Contest, once joked with me that if her contest banned scripts about writers they’d probably lose a quarter of their entries. I did the math once and in one contest I read for almost 15% of the scripts had a writer as one of the main characters.

No one cares about the day-to-day struggles you go through as a writer. No one. Especially not a bunch of script readers who are probably disgruntled writers themselves. If you’re being sincere, you’re going to bore them (see The True Script up above). If you’re making up some silly idealized writing lifestyle, they’ll call shenanigans on it. And then they’ll pistol-whip you for saying shenanigans.

Let’s assume they didn’t toss the script aside as soon as they saw the writer character. If they get to the end and said character finally sells their book or screenplay and wins the Pulitzer/ Oscar/ whatever… the reader will crumple your script into a ball and hurl it away from themselves. Then they will burn it so nobody else will have to read the damned thing. Then they will get your personal information from the contest director, hunt you down, and pistol-whip you.

I am dead serious about that.

There you have it. Eight scripts that will set a contest reader against you from the start. Again, I’m not saying it’s impossible to win with one of these screenplays. I am saying, though, that if you’re going to go this path you absolutely must knock it out of the park.

Next week, it’s time to finish this thing up.

Until then, go write.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the two federal agents (and the audience) pay attention to Indy’s lesson about Ark of the Covenant because it’s something they don’t know. After all, that’s not their field of expertise. Notice that in the same scene, Marcus isn’t listening with rapt fascination. He almost comes across as mildly bored, and he probably is because he already knows this.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the two federal agents (and the audience) pay attention to Indy’s lesson about Ark of the Covenant because it’s something they don’t know. After all, that’s not their field of expertise. Notice that in the same scene, Marcus isn’t listening with rapt fascination. He almost comes across as mildly bored, and he probably is because he already knows this.