My apologies for being a bit late, but I think this is worth it

This is going to be one of those screenwriting-centric weeks, although you could probably find some helpful hints. If nothing else, I’m feeling a little slappy this week so you’ll probably find it very entertaining.

It’s that time of year again. The big-gun screenplay contests have opened their doors and are accepting entries. Thousands of scripts are pouring in,

ready to be judged, all with the hope of winning fortune, fame, and possibly a whole new life.

Really, who needs that kind of pressure?

It’s so much easier not to win, isn’t it? Less work, less effort, and less responsibility. Nobody really wants to deal with the money or the buzz or the constant calls from agents and managers and studios, right?

As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve watched this play out from both sides. I used to read for a few contests and spent long days and nights going through script after script, often seeing the same mistakes again and again. I’ve also placed in a bunch of contests– and when I say placed I don’t mean I got the honorary quarter-finalist position that was given to everybody who entered. I’ve won prizes and been singled out a few times.

So I know the kind of things that make a reader cringe and shake their head. The things that make them shout and scream. In one or two cases, only the timely intervention of booze kept me from gouging my own eyes out.

I’m going to share those secrets with you right now. Here are eight insider tricks which will help you ensure that your screenplay never makes it past the first round. In fact, if you can manage all of these, your script will go down in flames.

And that’s what we all want, right?

Don’t Worry About Spelling

Spelling is one if those outdated, elitist things that pretty much

every contest uses as a general guideline, even when its painfully abhorrent whit some won meant too spill. That makes this then easiest way to fail. All I need to do is trust in my idiot spellchecker and never bother to look anything up. A dozen or so

misspelled and misused words in the first ten pages of my script will make sure any reader is biased to think I have no idea what I’m doing, and that means any good stuff that accidentally slipped into my story later on will be viewed with a much, much more critical eye.

Don’t Bother With Punctuation

When I screw up my punctuation, it really grates on a reader’s nerves because it affects how they take in the story? This is a slow, cumulative, thing that can really kill my chances and help swing the vote if someone’s on the fence, about my manuscript! And anything, that can help lower my chances of moving on, is a good thing, right.

A fantastic, screw-turning punctuation mistake is not knowing

how to use apostrophe’s. Yeah, they’re almost always used to show possession, almost never plurals, but it’s easy to forget that simple rule and use them for lot’s of thing’s. Not knowing it’s or its is a great one that will make sure the reader can’t take me seriously as a writer. That’s one of those easy mistakes that will make the odds of winning inch away little by little until it’s a good, safe distance away.

Ignore the Rules

Contest have a lot of weird, arbitrary rules and requirements. Some only want to see certain genres or themes. Others won’t take adaptations. A few of them will even put certain requirements on me as the screenwriter.

I make a point of sending torture porn scripts to competitions that are looking for strong family themes and morals. I submit romantic comedies to sci-fi contests. If it’s for feature films, I send them the television pilot I wrote in college. I make it a point to go at least ten pages past the maximum acceptable length. If the competition is only for women or minorities, I make sure there’s a picture of my pasty-white junk on the cover so the readers know beyond a shadow of a doubt that I’m an Anglo-Saxon male.

Doing something completely unacceptable like this takes a little more effort on my part, but it’s a pretty much guaranteed way to make sure I fail.

Don’t Sweat Formatting

Hollywood is like any industry, and “industry-standard” is a term that shifts and changes all the time. Learning

the current, proper script format is tough, and can require typing things into Google and then looking at the results. I don’t know about you, but I just don’t have time for stuff like that.

As I see it, all these rules about headers and sluglines are just as arbitrary as spelling and grammar. If I must format something, I like to use classic screenplays from the ‘40s and ‘50s as my guideline. After all, if that page layout was good enough for Casablanca it’s good enough for people today.

Casablancawon an Oscar, you know.

I’ve even submitted stage plays to a few screenwriting contests. Because at the end of the day, it’s still going to be a story in front of an audience, right? I’ve never been clear why this gets some readers so frustrated that they start marking down for it. The important thing, from our point of view, is that we can depend on them to do it and keep us out of that semi-finalist round.

Submit A First Draft

The people who want to win often do

a second draft. Sometimes even a third. They cut and rewrite and restructure and a bunch of other stuff that… well, you’d need to be a screenwriter to understand. It’s a lot of work to get into that very uncomfortable position of being the winner.

I prefer to go off the assumption that my work is perfect and needs no alterations or adjustments of any kind. It’s like

a diamond in the rough, just without the rough part. It doesn’t even need polishing. This is a great mindset to be in, because when my script gets rejected it casts all the blame squarely on the reader. Because my script was perfect.

Bam. How great is that? No work. No pressure. No winning. It’s a screenwriting trifecta.

Submit the Script You’re Going to Direct

This method succeeds in getting me kicked out of the contest for a few reasons. I don’t need to learn formatting, because it’s just going to be for me, Colleen, Patrick, and Sam. I don’t need to explain a lot of stuff or go into detail because we all know what we’re talking about. And it saves me time because I don’t need to take out all the stage directions, camera angles, parentheticals, editing notes, and other things cluttering the script. You know, the stuff I added in to help me out when we shoot this next summer in Marcus and Gillian’s garage.

See, readers are going to get hung up on all this stuff and say

it’s not relevant. That’s just a bonus. Now when I get rejected, I’ve got proof Hollywood doesn’t recognize my genius. And probably that the contest is rigged. In favor of people from Hollywood.

Base It On A True Story

Okay, if I want to use this method to lose, one of the first things to do is make sure the reader knows this is based on a true story. I need to put it on the cover, preferably as part of the title. Opening monologues that explain this is all based on real events are good, closing monologues are better. If I can figure out how to do both, that’s great. Being very clear about this up front puts all the pressure on the readers, because now they

must find my story believable.

Because it’s true.

The next thing is to make sure the true story I’m basing this on is very boring and common. If it’s something that happens to, say, half the people on earth in a given year, that’s excellent. A quarter of the population isn’t bad, but I really want my true story to be as banal as possible. It’ll improve my chances of failure a lot if the events can actually be dull in and of themselves, so I need to be honest with myself about how interesting they are. I don’t want to mess up and tell a story that most people might actually want to see on the big screen.

This one’s a bit tougher because I’m depending on everyone else in the contest to make up stories that are inherently more interesting than my true one. Which isn’t that hard, but I don’t want my failure to hinge on someone else doing a better job than me. So it’s best to choose a topic like

cancer, a non-competitive sporting event, or maybe something about a gutsy schoolteacher. These things will almost always drag my script right down, assuming the reader can stay awake long enough to judge it.

Make It As Hard to Read As Possible

Last but not least, this is the knockout punch in my “losing a screenplay contest” arsenal. If for some reason I can’t use any of the above tricks or angles, I need to actually make the script itself difficult to read. Using a non-standard font is good for this, and only takes a few clicks of my mouse to get the script out of Courier and into something unacceptable like , Garamond, or Papyrus.

Another good trick is

shrinking the font. Readers see enough scripts every day that they’ll immediately notice this and it will drive them nuts, trust me. The downside is this will actually make my script shorter, so if I do this it means I have to make my script

even longer so it stays past the maximum acceptable length (as mentioned above). If I’m not careful, this can lead to a vicious circle where I eventually end up with a 400,000 word script in 6-point font, and that’s a lot more work than I want to put into a contest I’m trying to lose.

There are some other tricks, too,

like giving lots of characters similar names (David, Davila, Danny, Danielle, Darcy). You can also try naming every character, including bit parts and non-speaking roles. Y’see, Timmy, this will confuse the hell out of a reader and make them waste a lot of time trying to keep things straight, and that will get them really frustrated with my script. I can also confuse them by naming and describing as many characters as possible at the same time. I like to call this “the dump truck approach.”

And there you have it. Eight sneaky tips and tricks you can use to make sure your screenplay never gets past the first round of judging. You might like to know these methods also work if you’re submitting to agents or film studios.

So, take the easy way out and avoid all that extra work and stress.

Don’t win.

I’m going to be taking next week off while I deal with a lot of things for the re-release of Ex-Heroes (available everywhere Tuesday the 26th). But Thom Brannan, author of Lords of Nightand co author of Pavlov’s Dogs, is going to sit in and talk to you a bit about getting stuff out of your head and onto the page. Then I’ll be back the week after to talk about one of my favorite topics.

Until then, go write.

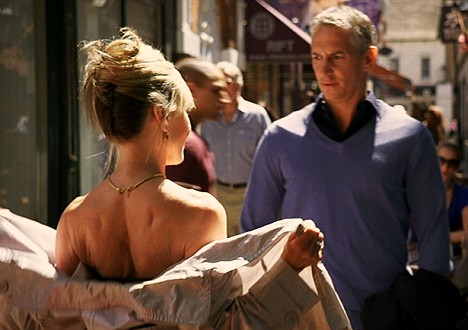

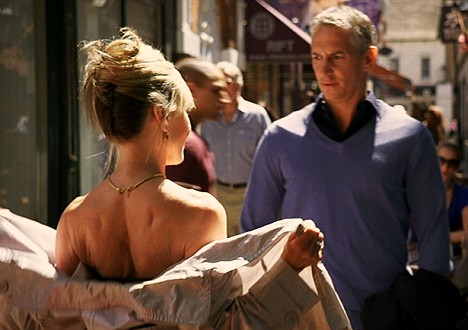

Because if I don’t know my words, my story starts to become muddled and unclear. And I can’t be lazy and say “people will understand it from the context,” because using the wrong words changes the context. If Phoebe decides togrin and bear it, it means she’s not going to let on how much the current situation is getting to her. If she decides to grin and bare it, though, it means she just pulled her shirt open in a moment of naughtiness. That changes the whole tone of the scene, and it could really change our view of Phoebe as a character. So to speak.

Because if I don’t know my words, my story starts to become muddled and unclear. And I can’t be lazy and say “people will understand it from the context,” because using the wrong words changes the context. If Phoebe decides togrin and bear it, it means she’s not going to let on how much the current situation is getting to her. If she decides to grin and bare it, though, it means she just pulled her shirt open in a moment of naughtiness. That changes the whole tone of the scene, and it could really change our view of Phoebe as a character. So to speak.

Because if I don’t know my words, my story starts to become muddled and unclear. And I can’t be lazy and say “people will understand it from the context,” because using the wrong words changes the context. If Phoebe decides togrin and bear it, it means she’s not going to let on how much the current situation is getting to her. If she decides to grin and bare it, though, it means she just pulled her shirt open in a moment of naughtiness. That changes the whole tone of the scene, and it could really change our view of Phoebe as a character. So to speak.

Because if I don’t know my words, my story starts to become muddled and unclear. And I can’t be lazy and say “people will understand it from the context,” because using the wrong words changes the context. If Phoebe decides togrin and bear it, it means she’s not going to let on how much the current situation is getting to her. If she decides to grin and bare it, though, it means she just pulled her shirt open in a moment of naughtiness. That changes the whole tone of the scene, and it could really change our view of Phoebe as a character. So to speak.