Or a drama king. I don’t judge…

When we left off, I’d just finished babbling about narrative structure, which is how my readers experience a story. Before that was linear structure–how my characters experience a story. This week, I want to talk about how those two structures come together within a

dramatic structure to form the actual story.

Warning you now, this is going to be kind of big and rambling, but I’ve also included a lot of pictures. Go grab a snack now and hit the restroom. No one will be admitted during the dreadful story dissection scene…

Also (warning the second), the story I’m going to dissect is The Sixth Sense. If you’ve never seen it and somehow avoided hearing about it until now, stop reading and go watch it. Seriously, if you’ve made it this long without having someone blow it for you, you need to see that movie cold. People love to give M. Night Shyamalan crap, but there’s a reason The Sixth Sense made him a superstar writer-director. So go watch it and then come back. The ranty blog will be here waiting for you when you get back.

Seriously. Go. Now.

Okay, everyone back?

As the name implies, dramatic structure involves drama. Not in the “how will I make Edward love me” sense, but in relation to the building interactions between the elements of the story. In most cases, these elements will be characters, but they can also be puzzles, giant monsters,

time limits, or any number of things that keep my protagonist(s) from achieving his or her goal. Any story worth telling (well, the vast, overwhelming majority of them) are going to involve a series of challenges and an escalation of tension. Stakes will be raised, then raised again. More on this in a bit.

Now, I don’t mean to scare you, but I’ve prepared a few graphs. Don’t worry, they’re pretty simple and straightforward. If you’ve been following the ranty blog for a while, they might even look a little familiar.

|

| graph #1 |

On this first graph (and all the others I’ll be showing you) X is the progression or the story, Y is dramatic tension. This particular graph shows nothing happening (the blue line). It’s an average day at the office, or maybe that long commute home on the train. It’s flat and monotone. No highs, no lows, no moments that stand out.

Boring as hell.

Harsh as it may sound, this graph is a good representation of a lot of little

indie art films and stories. There are a lot of wonderful character moments, but nothing actually happens. Tonally, the end of the story is no different than the beginning.

|

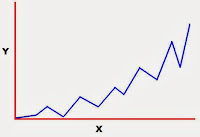

| graph #2 |

As a story progresses, tension needs to rise. Things need to happen. Challenges

need to arise and be confronted. By halfway through, the different elements of the story should’ve made things much more difficult for my main character. As I close in on the end, they should be peaking.

Mind you, these don’t need to be gigantic

action set pieces or

nightmarish horror moments. If the whole goal of this story is for Wakko to ask Phoebe out without looking like an idiot, a challenge could be finding the right clothes or picking the right moment in the day. But there needs to be something for my character to do to get that line higher and higher..

Now, here’s the first catch…

|

| graph #3 |

Some people start with the line up high. They begin their story at eight and the action never stops (I’m looking at you,

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest). This doesn’t leave a lot of room for things to develop, but the idea is that you don’t have time to see that because we’re hitting the ground running and going until we drop.

You might notice the line on this graph looks a lot like that first one up above. It’s pretty much just a straight line because there isn’t anywhere for things to go. And, as we established,

straight lines are pretty boring. They’re monotone, and monotone is dull whether the line’s set at one-point-five or at eleven.

|

| Rising with setbacks |

That’s the second catch. Dramatic structure can’t just be a clean rise like that second graph. That’s another straight line. And straight lines are… well, I’m sure you get it by this point. In a good story, there will be multiple challenges and the hero isn’t going to succeed at all of them. He or she

will win in the end, of course, but it’s not going to be easy getting there. They’ll face mistakes, surprises, bigger challenges, and determined adversaries. For every success,

there’s going to be some setbacks. So that blue line needs to be a series of peaks and drops.

If you know your physics, you know that we don’t feel a constant velocity. Think about riding in a car. As long as it’s a steady speed, you don’t notice. You can drink coffee, move around, whatever. What we feel is acceleration—the change in velocity. Those ups and downs are when things stand out, when we know something’s happening.

Make sense?

So, with that in mind, here’s a big graph.

This is everything together. X is narrative structure. It’s the story progressing from page one until the end of my story, novel, or screenplay. Y is dramatic structure. We can see the plot rising and falling as the characters have successes and failures which still continue to build. And the letters on the blue line are the linear structure. We’re beginning at G, but there are two

flashbacks in there that go back to A and D.

Notice that D-F flashback. Even though it’s near the end of the story, it’s got more dramatic weight than G through K. This is the big, easy trick to dramatic structure. No matter what my narrative is doing, it has to keep increasing the tension.

Y’see, Timmy, this graph is what pretty much every story should look like if I map it out. They’re all going to start small in the beginning and grow. We’ll see tension rising and falling as challenges appear, advances are made, and setbacks occur. They’re not going to be exactly like this, but the basic structure—an escalating, jagged line—is almost always a given. Small at the start, increase with peaks and dips, finish big.

Simple, yes?

Keep in mind, this isn’t an automatic thing. This is something I, as the writer, need to be aware of while I craft my story. If I have a chapter that’s incredibly slow, it shouldn’t be near the end of my book. If a scene has no dramatic tension in it at all, it shouldn’t be in the final pages of my screenplay. And if it is, it means I’m doing something wrong.

Now, that being said, it should be clear that where things happen within a narrative is going to effect how much weight they have. Again, dramatic structure tells us that things in the beginning are small, things at the end are big. Something that’s an amazing reveal at the end of the story

won’t have the same impact at the beginning.

Let me give you an example. It’s the one I warned you about at the top. I’d like to tell you an abridged version of

The Sixth Sense. But I’d like to tell it to you

in linear order.

Ready?

The Sixth Sense

The Sixth Sense is the story of Malcolm, a child therapist who is killed by one of his former patients in a murder-suicide. Malcolm becomes a ghost, but doesn’t realize he’s died so he continues to “see” his patients. Several months later, across the city, a woman becomes jealous of her new husband’s daughter, Kyra, and begins to slowly poison the girl. It’s about this time that Malcolm meets Cole, a little boy with the power to see ghosts, and decides to take Cole on as a patient, helping him deal with the crippling fear the ghosts cause. When Kyra finally succumbs to the poison and becomes a ghost, she finds Cole, too—inadvertently terrifying him when she does. Malcolm suggests to Cole that helping her might help him get over his fear. Cole helps expose Kyra’s stepmother as a murderer and also helps Malcolm come to realize his own status as one of the deceased. And everyone lives happily ever after. Even the dead people.

The happily ever after is a bit of an exaggeration, granted, but it should make something else clear. When the narrative of this story follows the linear structure, a huge amount of drama is stripped away. It’s so timid and bland it almost reads like

an after-school special rather than a horror movie. A lot of the power of this story came from

the narrative structure. The order Shyamalan told this story in is what gave it such an amazing dramatic structure (and made him a household name).

This is what I’ve talked about a few times with flashbacks and non-linear storytelling. There needs to be a reason for this shift to happen at this point—a reason that continues to feed the dramatic structure. If my dramatic tension is at seven and I go into a flashback, that flashback better take it up to seven-point-five or eight. And if it doesn’t, I shouldn’t be having a flashback right now. Not that one, anyway.

For the record, this is also why spoilers suck. See, looking up at the big graph again, E is very high up in the dramatic tension. It’s a big moment, probably a game-changing reveal, in a flashback. If I tell you about E before you read the story (or see the movie or watch the episode or whatever), I’ve automatically put E at the beginning–it’s now one of the first events you’ve encountered in the narrative. And because it’s at the beginning, it’s now equal to G in dramatic tension. Because things at the start of the story always have very low tension ratings.

|

| why spoilers suck |

The thing is, though, E isn’t at the start of the story. It’s near the end. So now when I get to where E really is in the story, it isn’t that big spike anymore. It’s down at the bottom. The dramatic structure of the story is blown because I didn’t get that information at the right point. It even looks wrong on the graph when the blue line bottoms out like that.

If you want an example of this (without giving anything away), consider

Star Trek Into Darkness. I can’t help but notice that a lot of people who were

demanding to know plot and character information months before the movie came out were also the same ones later complaining about how weak the story was. Personally, I went out of my way to avoid spoilers and found the movie to be very entertaining. It wasn’t the most phenomenal film of the summer, but I had a lot of fun with it

It’s dismissed as coincidence.

Now, here’s one last cool thing about dramatic structure. It makes it easy to spot if a story is worth telling. I don’t mean that in a snide, demeaning way. The truth is, though, there are a lot of stories out there

which just aren’t that interesting. Since I know a good story should follow that ascending pattern of challenges and setbacks, it’s pretty easy for me to look at even the bare bones of a narrative and figure out if it fits the pattern.

For example…

By nature of my chosen genre, I tend to read a lot of post-apocalyptic stories and see a lot of those movies. I’ve read and watched stories set in different climates, different countries, and with different reasons behind the end of the world. I’ve also seen lots of different types of survivors. Hands down, the least interesting ones are the uber-prepared ones. At least a dozen times I’ve seen a main character who decides on page five to turn his or her house into a survival bunker for the thinnest of reasons, filling it with food, weapons, ammunition, and other supplies. But twenty pages later, when the zombies finally appear… damn, are they ready. Utterly, completely ready.

In other words… there’s no challenge. There’s no mistakes, no problems, no setbacks. The plot in most of these stories just drifts along from one incident straight to another, and the fully prepped, fully trained, and fully loaded hero is able to deal with each one

with minimal effort. That’s not a story worth telling, because that story is a line. And I’m sure you still remember my thoughts on lines…

On the other hand we have C Dulaney’s series,

Roads Less Traveled. The series begins with

The Plan, protagonist Kasey’s careful and precise strategy for surviving the end of civilization. But almost immediately, the plan starts to go wrong. One of the key people doesn’t make it, a bunch of unexpected people do, and things spiral rapidly downward. Challenges and setbacks spring up as the tension goes higher and higher.

That sound familiar?

And honestly… that’s all I’ve got for you. I know I’ve spewed a lot, but I wish I could offer you more. Y’see, Timmy (yep, it’s another double

Y’see, Timmy post), while the other two forms of structure are very logical, dramatic structure relies more on gut feelings and empathy with my reader. I have to understand how information’s going to be received and interpreted if I’m going to release that information in a way that builds tension. And that’s a lot harder to teach or explain. The best I can do is point someone in the right direction, let them gain some experience, and hopefully they’ll figure it out for themselves.

So here’s a rough map of dramatic structure.

Head that way.

Next week, I’ll probably blab a bit about Watson, the supercomputer.

Until then… go write.